“Being deeply loved by someone gives you strength, while loving someone deeply gives you courage.” – Lao Tzu

When compared to the men’s events, the early Olympic authorities allowed few competitions for women athletes. The marathon and the 800 meters race, for example, were introduced for men in 1896, for women, however, it was not until 1928 before the 800 meters was sanctioned and 1984 at the Los Angeles Olympics before the women’s marathon was staged. For years, many other sporting competitions were denied to women because they were considered to be either too strenuous or perhaps too unladylike. Similarly in Japan, it is only in recent decades that women have been allowed to compete in the full gamut of practically all modern-day sporting pursuits. Looking at the situation in retrospect, the big surprise is how well Japan’s female athletes have performed not only in national but also in world and Olympic competitions, especially so in soccer, ice dancing, wrestling, swimming, volleyball, gymnastics, marathon races and in contest judo, too.

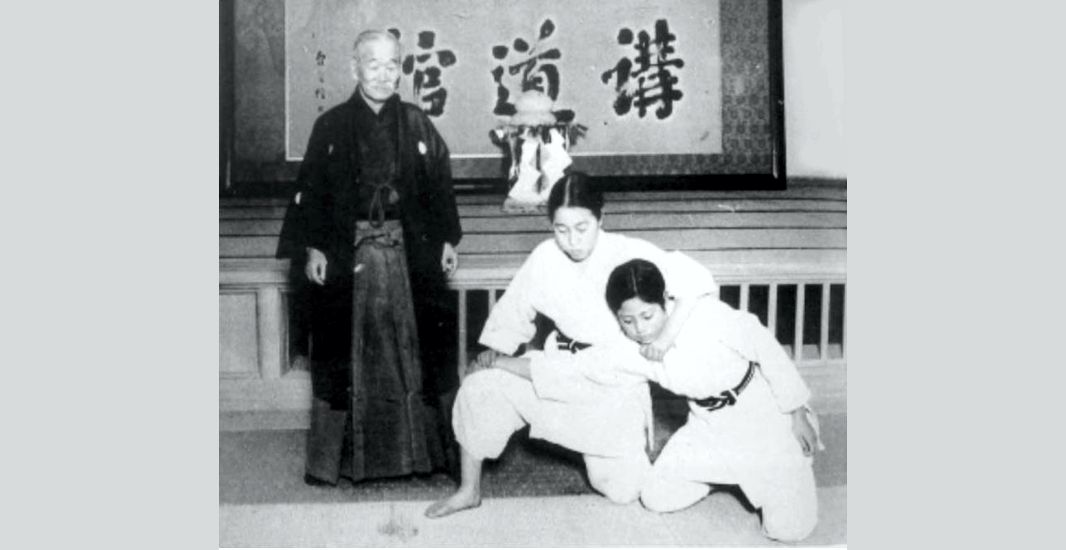

In the earliest days of judo, it seems that most people, including Jigoro Kano himself, considered jujutsu and judo to be activities suitable for males only. Around 1900, however, things slowly began to change. Noriko Yasuda and a few other women inquired if they could learn judo at the Kodokan. It appeared that because Kano had made no arrangements to include women in Kodokan membership, he showed some reluctance at first. After discussing matters with his wife and others, however, he agreed to interview 33-year-old Noriko Yasuda. She informed Kano that she had suffered mental anguish as an adopted daughter, mentioned her husband, an army officer, and about her being weak and sickly from childhood, which had all taken a toll on her health. She said that she had even considered suicide to stop the suffering, and so she wished to improve both her physical and her mental condition.

Kano, who was always methodical in his approach to everything, subsequently devised physical exercises for Yasuda and advised her to change from her usual diet to one that he advocated for her. He later presented her with three large and three small dumbbells and instructed her how to use them. She related that the purpose was not to increase muscular power but how to move and use her body and how to concentrate strength in her right hand. For the first week he told her to lift the dumbbells straight up with her right hand. The next week she should lift to the sides and the following week to lift them overhead. These repetitions she was advised to do three times a day. After she had suitably accomplished these tasks, Kano started to teach her kata. Two months later, he taught her, over a period of one month, how to do break-falls. Yasuda said that by that time she was feeling much better both physically and mentally. At this juncture, however, Kano decided to send her to hospital for a medical check up. Upon learning from her doctors that her prognosis was a satisfactory one, Kano informed Yasuda that he would in future concentrate on teaching her randori.

One of the customs started by Kano in those days was for his male Kodokan students to go on hiking tours at weekends, and sometimes, to climb Mount Fuji. Therefore, the next time that he had arranged such a climb he directed that she, Yasuda, and four of the other early women trainees accompany his six male judo students in scaling the famous peak in order to assess the physical capabilities of these women. Among the group, however, only Yasuda and Hisako Oba, later to become a famous author, succeeded in making the two-day trek to the top of the mountain, some of the others had difficulty breathing; others got frostbite, suffered from diarrhoea, or developed headaches.

When Kano learned of Yasuda’s accomplishment, he stated that he was now convinced that judo had indeed proved its worth in benefiting women’s health. He also said that in future he would make greater efforts to teach judo to women. On November 1, 1923 Kano appointed a chief instructor, Ariya Honda, to teach judo to women at the Kodokan’s Kaiunzaka Dojo. Noriko Yasuda was eventually graded to 1st Dan and appointed by Kano as an instructor at the Kodokan.

Since other women were also eager to learn judo, Kano officially opened up Kodokan membership to include women. There were, however, no arrangements made to stage any contests for them. Later, a gradual increase in interest came from foreign women who also wished to learn judo. As a result, the first non-Japanese woman to attain a black belt grade was a blonde-haired English woman by the name of, Sarah Mayer; (1896-1957) who had received initial judo instruction from the famed Yukio Tani (1881-1950) and Gunji Koizumi (1885-1965) at the Budokwai in London, UK. In 1934, although married, she traveled to Japan in order to train at both the Kodokan in Tokyo and later at the Butokukai in Kyoto over a total period of some two eventful years before being awarded a 1st Dan in February 1935. After returning to the UK to rejoin her husband, Robin, she opened a dojo at her home at Burgh Heath, Surrey, where she taught judo. She wrote a play ‘Hundreds and Thousands’ staged at the Garratt Theater in 1939 and also periodically submitted articles for publication in the Evening Standard newspaper.

Ultimately, more and more Japanese and foreign women started to take a serious interest in the study of judo. Among the most celebrated of Japanese women judoka was 10th Dan Keiko Fukuda (1913-2013) the granddaughter of Hachinosuke Fukuda (1827-1879) Kano’s early Tenjin Shinyo jujutsu master. Keiko graduated from Showa Women’s University where she obtained a degree in Japanese Literature and who at the advanced age of 99 years, was declared the last surviving student of Jigoro Kano. Keiko spent most of her life in the US where she taught judo and occasionally travelled overseas to give judo seminars. She also established her own dojo, the Soko Joshi Judo Club, where she taught for some 40 years. According to her life-long friend, Shelley Fernandez, ‘Keiko Fukuda took to heart Kano’s request that his students travel the world to teach judo – she was the only one who did so’.

In more recent times, along with the introduction of competitive judo for women, came many extraordinary female contestants, these include the remarkable Ryoko Tani, (maiden name, Tamura) Japan’s most successful ever contestant, victor of seven world championships, in addition to capturing two Olympic gold medals, two silvers and one bronze. In the UK several British women also had distinguished international contest careers, from the days of Jane Bridge, when in 1980 she became the first British woman to win a world judo gold medal, to the later days of the great Karen Briggs, four times world and five times European champion. Diane Bell, Ingrid Berghmans (Belgium) and several other European women also had outstanding contest careers. In the US too, recent renowned female competitors include Olympic bronze medalist Ronda Rousey, and her mother, AnnMaria De Mars, who won gold at the 1984 World Championships under her former name of Ann-Maria Burns. More recently, the current most outstanding female judo athlete is the double Olympic gold medalist Kayla Harrison.

In retirement many former competitors become school or sport teachers. Professor Jigoro Kano, himself a well-known academic, was always keenly aware of the huge importance of education, and so left to posterity several calligraphic quotes such as the following: “Nothing under Heaven is more important than education. The teaching of one virtuous person can influence many. What has been well learned by one generation can be passed on to a hundred generations to come.”

Also, worth quoting is:

‘the hand that rocks the cradle is the hand that rules the world.’

William Ross Wallace

(1819-1881)

Brian N. Watson

May 6, 2018

Tokyo, Japan

References:

The Father of Judo, B.N. Watson, Kodansha International, 2000, 2012

IL Padre Del Judo, (Italian) B.N. Watson, Edizioni Mediterranee, 2005

Judo Memoirs of Jigoro Kano, B.N. Watson,Trafford Publishing, 2008, 2014

Memorias de Jigoro Kano, (Portuguese) B.N. Watson, Editora Cultrix, 2011

Saving Japan’s Martial Arts, Christopher M. Clarke, Clarke’s Canyon Press, 2009

A History of Judo, Syd Hoare, Yamagi Books, 2009

Jigoro Kano & the Kodokan, Translated by Alex Bennett, Kodokan, 2009

(This essay may be sent to others; my wish is that no alteration be made to the text. B.N. Watson)