The warrior spirit lies deep within us all. It’s a vital, rousing force that can turn the meek into the fearsome.

To be effective in self-defense, you cannot just defend—you must attack back. For a female, this is the ultimate reversal: You become the huntress, not the hunted; the predator not prey. You summon and unleash all your life forces—courage, will, wrath, cunning, physical powers—and use them like secret weapons. Nothing is out of bounds; nothing is unthinkable. There’s little to compare this to: you dial up the creature within; you trade in your polite self for your animal-self; you issue the “sic” command and give that beautiful junkyard bitch within carte blanche permission to go for the throat. ~ Melissa Soalt, from “Fierce Love: The Heart of the Female Warrior”

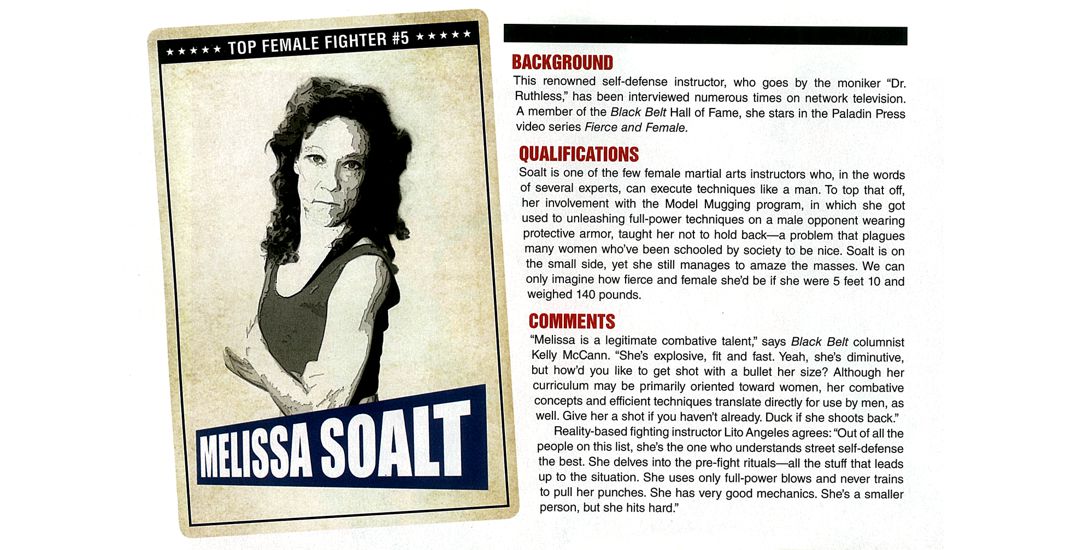

Shortly after my Fierce and Female videos came out, I ran across a review by a self-defense pro whom I highly respect: “She has more balls than most men I know,” he raved. I was flattered, all right, but . . . balls?

I have received this comment before and always take it in the complimentary spirit in which it is meant, but it speaks volumes to the association between courage and manhood, between courage and virility and just how deeply this association embeds in our language and culture.

This is something I should like to change.

The warrior spirit lies deep within us all. It’s a vital, rousing force that can turn the meek into the fearsome. Women, as a tribe, are endowed with their own warrior instincts and powers, borne in the female psyche and biology.

For example, classical warrior texts call for a dispassionate mind-set, devoid of emotion: you must control your fear, control your emotions, they say. But that, I protest, is part of a male paradigm. While it’s true that strong emotions can hijack body and mind—“Don’t let your emotions get ahead of your technique,” I tell my students—it’s precisely the swells of rage, terror, and love itself that funds a woman’s fight, fueling her body, enabling her to evoke the warrior spirit—be it to protect herself, loved ones, or the sovereignty of her peoples.

Rage. Terror. Love. Fury. These aren’t words you’re likely to find in any warrior’s code or combat manual. Yet fighting and the business of being a warrior is an emotional and primal reality as much as it’s a moral and spiritual one.

For 18 years, I’ve been teaching women how, when all else fails, to shed their civilized skins, unleash their Savage Beauty, and attack back—not like playful kittens, like wolverines. (The goal, of course, is to facilitate escape.) But I am also a woman who’s been assaulted and fought back. At five feet tall on a good hair day, I can attest: It’s not the size of the woman in the fight; it’s the size of the fight in the woman!

Fighting spirit is a lot like beauty—it’s both innate and can be cultivated, but always kindled from the inside out, whereas power is a commodity that can be sourced from many places. And I have siphoned power from violating hands: from rapacious hands that stole pieces of me in the darkness, trying to evict me from my very own body; from the sweaty pulp of my would-be rapist’s palm slapping over my mouth as he bashed my head against the wall (I struck back and escaped); from hands that tightened like a noose around my throat, before I spit in my attacker’s face and a vicious fight ensued; from the hand that I broke that wouldn’t take NO for an answer. (That was a dawning recognition: my body was a tool and instrument of power, and with this tool I too could be dangerous. A knowing, long before I had any training, that I have since passed to countless women.)

Power is also kindled by fear. I’m talking about primal, animal-level fear. The kind that Ambrose Redmoon, Native American warrior and writer, so aptly described “could pull the flesh off your face”—which I think should be a requirement for anyone teaching self defense. If you haven’t been scared to death you don’t qualify, especially when it comes to teaching women, most of whom are already experts in fear, many of whom have fought their very own “War on Terror.”

Terror is the mother of all fear. You know it when you feel it. An icy chill rips through your body at warp speed, catapulting you into a Darwinian world of predator and prey. When I unpack my memories, I can still feel the terror I felt when a man shrouded in darkness broke into my home in the dead of night, after first cutting the power and phone lines, then headed for my bed—knife in hand. Fortunately I repelled his advances with a Godzillian yell from Hell. This incident is what led me from martial arts to the down-n-dirty methods that would become me.

That memory still haunts like a ghost from time to time. But the terror itself has been absorbed, eaten, you could say, and transformed into fuel in the belly of the beast. Now, when the memory arrives that chill turns cold blooded—the French call it sang-froid —and is seasoned with invective. From the neck up I am ice; from the neck down, I am fire. I imagine tearing into this man using everything at my disposal—my bare-naked body, the walls, furnishings, improvised (and not so improvised) weapons.

So I know a thing or two about this dirty business. This intimacy is no doubt part of what the reviewer perceives in my demeanor and “spirit of entering” and identifies as balls. But frankly, I would attribute it to primal rage and fear.

My own stories pale by comparison. As a former psychotherapist, I have companioned survivors of violence and assault into netherworlds of horror where moments can unravel into lifetimes of suffering. I am not the first to say this, but sexual and bodily attacks are microcosms of war leaving heaping smoking mounds of devastation in their wake. And let me tell you: it ain’t a pretty picture. The effluvia of rape and child abuse stinks, and makes you want to sob. So my mettle, you could say, also comes from heartbreak hardened into resolve. And from e-mails alerting me to atrocities against women all over the world; they flash across my computer screen like smoke signals from afar—and not so far. Women being tortured and burned and killed and gang-raped by civilians and soldiers alike; beaten because they were handy when “his” demons struck. This makes my skin crawl, and it incurs my wrath.

We have nice, civilized, air-fluffed terms for this feeling: Righteous rage. Moral indignation. But what I feel is far more primitive: Each story fuels my fire and undying reverence for female disobedience, adding another stripe to my war face.

So this essay is really a call to arms which I hope will awaken women’s warrior spirit, shatter myths of female defenselessness, and topple some unspoken enemies: the cavernous divide between femininity and aggression (into which many victims have fallen); the insidious New Age notion that flow is not compatible with force; a culture that rewards women’s “looks over competence” and wants women to believe that confidence comes in a roll-on. (Don’t even get me started on the farcical term “feminine protection.” Protect what—our underwear?)

Oh sure. There’s progress. Let’s not forget Hollywood, where a woman can be a deadly dame but first she has to give good face and qualify as “babealicious.” The mandate is clear: You can act tough, but keep it pretty, not gritty.

Reclaiming the Killer Instinct

No creature on Earth other than humans has done such a menacingly fine job of socializing the killer instinct out if its females. As a feminist, it would be a tidy coup if I could blame all this on the “evils of patriarchy.” But it isn’t just age-old conservatism or ads boasting, I live for a great halter top! that atrophies the female-animal muscle, truncating women from their baser selves. Popular New-Ageism and “moon-to-uterus” spirituality co-conspire in this pacification and would like us to believe that women are innately all-beatific, all-nurturing, do-no-harmers with nary a virulent, aggressive, or power-loving bone; that we are always the embodiment of the “peaceful warrior goddess,” always ennobling our higher, holier selves while disavowing our dark side and bestial potential. (Frankly, this doesn’t sound like any woman I know. Can the notion of men as all malevolent be far behind?)

Nowadays, we hear a lot about higher callings, the yearning to connect with forces greater than one’s self, and about the power of returning to one’s roots. This is precisely the gift of self-defense—it returns women to native powers buried beneath fear and the rubble of socialization, and it bestows saving graces—not from heaven above, but from below—from our lower center of gravity curiously located near the site of the womb. (More reasons why self-defense is a womanly art!)

Self-defense is not a sophisticate: It’s raw; it’s primal. It involves a descent into a subterranean strata of your being, far below the topsoil of the nice lady cammo. Here lies a respite from the ubiquitous hum of civility: the meaty thuds, the heated rush, the bellowing sounds all part of its primitive appeal. There’s magic too: learning to fight back locates women back in time, long before plastic bosoms, bikini waxing, and feminine deodorants, returning us to an earlier Self. Each thwacking blow, each bellicose yell peels back a layer of the modern-day veneer until, stripped to our essence, we uncover what anthropologist Michele Rosaldo has called “The image of ourselves undressed,” the stuff we are made of at the core—a vibrant and formidable mélange of Beauty and Beast, I attest. And it can knock a man out.

To be effective in self-defense, you cannot just defend—you must attack back. For a female, this is the ultimate reversal: You become the huntress, not the hunted; the predator, not prey. You summon and unleash all your life forces—courage, will, wrath, cunning, physical powers—and use them like secret weapons. Nothing is out of bounds, nothing is unthinkable. There’s little to compare this to: You dial up the creature within; you trade in your polite self for your animal-self; you issue the “sic” command and give that beautiful junkyard bitch within carte blanche permission to go for the throat.

I know this part of myself intimately—as all women should —and could no more disown this savage endowment than I could amputate a limb. Like my maternal nature, it is bedrock, or maybe it’s this simple: survival, like romance, has captured my heart.

Yet I speak of this love affair with some trepidation. In spite of a culture gone warrior-chic and the alarming fact the CDC (Centers for Disease Control) has identified sexual assault and violence as one of the greatest health concerns of the 21st century, my enthusiasm for “going animal” and teaching women how to morph their bodies into weapons of destruction makes some folks nervous. Maybe it’s the glint in my eye, but when I tell choice stories—like the one about the cocktail waitress who nailed her attacker’s foot to freshly laid tar with her stiletto heel—or when I gush about my Afghani knife and confess that at night you might find me in the darkness slicing the air as if across a man’s forearm, then neck—I am often flashed a look of disdain. The concern is that I have abandoned Venus for Mars; that my flight into the hardness of warriorhood represents a radical departure from the fleshy pink interior of femininity. That the Beast Girl’s cravings are an anomaly of nature.

Nonsense! Somewhere along the line, we lost life’s original instructions. What could be more natural, more in tune with Mother Nature than knowing how to bash back and not become prey or fodder for a scumbag’s amusement? But the concern is telling, and betrays an unspoken fear: that the tools of aggression/forceful resistance/use of force is coming to a female near you.

And it should. I think about my student Sheila who suffers brain seizures, a result of having been boxed in the head by her attacker. “Why didn’t anyone ever teach me what to do,” she laments. These are haunting words that resound in every women’s self-defense class.

If I were Warrior Queen for a day, I would issue a decree that all women become too dangerous to attack.

Myths & Misconceptions

No one would ever ask a man, “Hey there, manly man, what possessed you to learn to protect yourself from all manner of scum?” What a silly question that would be! In a man’s world, self-defense is deemed natural; it comes with beer and nachos and having a penis, whereas women are encouraged to rely on “good guys” to protect them from “bad guys”—a fundamentally flawed (not to mention disempowering) strategy because women are typically alone when violence strikes. Plus that good guy/bad guy line can get blurry, fast.

The underlying belief is that we aren’t made of the right stuff; that women are the weaker sex; that she’ll only get hurt worse, blah blah blah. What a screwball argument! Of course fighting back carries risks. And, yes, you might get hurt. Count on it; visualize it; become accustomed to the idea, I urge women, as though being raped, beaten, or slaughtered doesn’t constitute injury? Not possessing explosive counterattack and escape skills—the first few seconds are often the most critical—and hoping to be rescued by a savior in uniform blue, or simply hoping… is far more injurious to women than fighting back. Strategies aside, this archaic attitude reinforces the age-old pas-de-deux: Men are the protectors; women are the protectees. In other words, you, a wussy female are helpless against attack. Got it?

Tell that to the Chicago woman who, in 2001, bit off her would-be rapist’s balls. (Helluva floss job, I have to admit.) Or the Boston co-ed who feigned unconsciousness then sliced her rapist’s face with a razor from her purse; or my student who cracked her attacker’s head against the bumper of her car and made pulp out of his accomplice’s groin. Or “Kathleen,” who chomped her knife-wielding rapist’s finger down to the bone during a vicious attack. (Her story is recounted in Sanford Strong’s book, Strong on Defense.) “I was so enraged that I went primal. Just because I’m a woman doesn’t mean I can’t fight like an animal,” she vigorously declared.

Like I said, estrogen doesn’t exactly make us sissies. Female ferocity is hard-wired, as old as the womb itself. And this fighting capacity goes far beyond self-defense.

As I write this, I am surrounded by copious accounts of women warriors from every era and corner of the globe—from ancient warrior queens to modern-day guerilla fighters. While their stories often go untold, the list is as long as the world is wide: from Sri Lanka’s Tamil Tigers—a renowned and deadly fighting unit—to anti-Nazi resistance fighters; from the “Russian Battalion of Death” to petite martial nuns; from South American revolutionaries holed up in jungles to American frontierswomen homesteading with child in one arm and shotgun in the other. Armed with their love and their fury —and weapons, and explosives, and combat skills—women have always been fighters, willing to fight to the death to protect their brood, their land, and the sovereignty of their peoples.

These accounts lend veracity to Margaret Mead’s words that “When women disengage completely from their traditional role, they become more ruthless and savage than men.” When pressed to fight, she observed, “the aroused female… displays no built-in chivalry.”

Female militancy is almost always fueled by oppression and atrocities. “Women are reacting to their victimization with a matter-of-fact military vengefulness,” wrote Naomi Wolf in her feminist tome Fire with Fire when discussing Balkan women who have taken up arms. One woman she cites joined the fighting “because of the mistreatment, the killing, and the rape. When I am on the front lines, I don’t see any difference between the men and the women,” she states. Another woman Wolf cites, a Sarajevan doctor, remarks how a third of the women she treated for rape “waited to have their gynecological problem resolved and then went out and picked up a gun.”

But it’s the words of Marisa Masu, an Italian resistance fighter from World War II, that I find most sobering:

“At the time it was clear that each Nazi I killed, each bomb I helped to explode, shortened the length of the war and saved the lives of all women and children. . . . I never asked myself if the soldier or SS man I killed had a wife or children. I never thought about it.”

Her words point to disturbing truths about survival—how the unfathomable becomes fathomable, the unthinkable becomes doable; how the forces of dark and light, creation and destruction, the maternal and killing instincts are not opposites but merely a few degrees of separation apart.

I learned this lesson, myself, 28 years ago while on my maiden voyage into the world —I was living in Israel at the time—when a fierce killer instinct summoned my hand onto a machete leaving me ready and willing to slice-n-dice a man had he continued to close in and not opted to flee. A seed inside of me popped open, I felt a chink in my armor and a whiff of something ancient passed through me. I knew in a heartbeat—I could kill in self-defense. This potential is in our blood, and perhaps our souls, and it could save women’s lives.

And that is what I beseech.

I don’t mean to suggest that fighting back is the solution to violence against women, or that it’s always effective. But when you boil it down, the answer to why men violate women, or each other, may be simpler than we think: they do it because they can.

I too long for a more equitable world, and I abhor and oppose war and the horrors it wreaks. But until women reclaim the warrior spirit and know that we too can be dangerous creatures, and not just the endangered ones, we will never be safe or whole. As long as men are the sole agents of violence and women are the casualties of their actions, the spoils of war, the victims on the pointy end of male aggression, there will never be a balance of power between the sexes. Women will remain relegated to a subordinate status, too powerless or too fearful to resist the dominance and brutalities of others, limited by social contract and restraint in the ways in which we can express our own ferocities, yearnings, and fighting spirit.

Perhaps a more immediate reason to internalize warring women’s “play for keeps” attitude is this: whether a woman is fighting for her homeland or fending off a thug or rapist, it amounts to combat, requiring the same martial mind-set and unfettered willingness to attack back, to fight for one’s life. This calls for a brutish mind-set, enabling you to bring your weapons to bear, to survive the brutalities, and to take the hits. This is why, when learning to fight back, the sound that must erupt from a woman’s body is not a shrilling plea for help, but a bellicose war cry. Because it is.

In my world, it’s understood: The sanctity of love, the sovereignty of body and soul sometimes require acts of aggression, and the tools of violence are encoded in flesh.

The face of the warrior and the warrior spirit belongs to us all.

To learn more about her methods, messages and Fierce & Female videos,

visit Melissa Soalt’s website or contact her directly at: fear2power@aol.com

COPYRIGHT © NOTICE: This article is protected by Copyright law. NO copy, reproduction or reprinting without written authorization. All rights reserved.