Some concepts don’t seem to go together. This phrase is an oxymoron at first glance. Bushido is a principle, a philosophy, peculiar to feudal Japan, or one might surmise.

In this study, I want to consider the way of the modern (Christian) warrior. Speaking of an oxymoron, there’s another for you. A Christian warrior? Can such a creature exist? I ask you to suspend your objections and disbelief for a bit and let me try to explain this concept. Bushido for the modern, Western warrior.

We are martial artists, but first and foremost we are Christians. That would have to make us Christian martial artists and therefore, Christian warriors. Taking into consideration that every Christian is involved in spiritual warfare (whether he realizes it or not). Every Christian is a warrior. We recall the old refrain, “Onward Christian soldiers, marching as to war…”. We are indeed soldiers in God’s army. If not we are with the opposition. There are no neutral parties in this war; no conscientious objectors. We are in God’s army, or by default, in the opposing forces. That being said let us explore the concept of western Bushido.

Several years ago, a movie came out. It was entitled, “The American Ninja”. About the same time, or shortly thereafter a series of books called, “The Black Samurai” was released. I am an American and of African American lineage, but both of these titles offended my martial arts sensitivity. As a youth I embraced the oriental origins of the arts that I was so dedicated to. Stripping them of their Eastern heritages seemed all but blasphemous to my young mind. One of the things that made the martial arts so attractive to me was their exotic origins.

Back in the day, studying karate was like being in a Buddhist temple. It was esoteric with Eastern tradition, many of which had their origins in religious temples of one sort or another. Being a Christian and a minister, I have separated the arts that I study from their religious traditions, but I still hold to some of the philosophical ideals that were instilled into me as a young martial artist. One of these is the edict of Bushido.

Bushido was a philosophy that described the life of the warrior knights of feudalJapan. The concept wasn’t peculiar to onlyJapan. Many of the Chinese martial arts had their beginning in Buddhist or Taoist temples. Because of this, a strict moral discipline was demanded if one studied these arts. InKorea, there was the Hwarang society, which taught young warriors a way of life on and off of the battle field. These philosophies were very similar to the principles that governed the lives and the day to day actions of the Japanese Samurai. Even the knights inEuropeheld to similar codes. These codes were necessary so that trained warriors didn’t run unfettered through the towns and cities where they served or lived. No warrior lives his entire life on the battle field.

We are neither samurai nor Hwarang warriors, however much we may envision ourselves as such. By the same token, we aren’t knights of feudalEurope. Even so, we, as trained warriors must have a code, a set of moral and martial ethics that we live by. As Christians, we are held to strict moral and spiritual edicts that govern our everyday lives. These principles should serve the same purpose that these martial codes of ancient times did. They should serve to harness our aggression when we are not involved in combat or combative training.

Some years ago, while in the military, I spent time in the birth places of some of the Eastern martial arts that I studied. I had an opportunity to study Shorinji Kempo among several other martial arts. Shorinji Kempo is considered an extension of Konga Zen Buddhism and as such is considered a religion. One of the principles that they taught was that if one practiced and developed the ability to hurt and kill, he should also develop the ability to heal and save lives. Along with the martial practices that they advocated they also taught a number of Eastern healing arts. This was an example of the Eastern principle of Yin and Yang, or the balance of opposites.

Obviously, we aren’t Zen priests and we should not engage in the practice of any art that serves to worship ‘other gods’. I don’t advise anyone to immerse themselves in these practices because of the spiritual implications, but I learned something from these studies. I learned that in the life of every warrior, there must be balance. If a man’s entire life is dedicated to maiming and killing, his worth as a profitable human being is put in question. A soldier’s purpose must be to preserve the lives of those he contends for, not just the taking of life. As warriors, we can’t sacrifice our humanity for the sake of becoming lethal fighters.

How does one balance the benevolent and the malevolent areas of life that the varying circumstances places upon a warrior? That has been the challenge that has faced martial arts instructors since men were first taught the intricacies of combat. As instructors, our goal shouldn’t be to produce rabid fighting machines with no goals or guidelines. Likewise, as practitioners, we should embrace our spirituality and our humanity. Otherwise, what we become is just a bunch of trained killers.

Because of the level of training I was exposed to in the military and the affects of combat, there was a debriefing period that we went through prior to discharge. Maybe nothing like in the movies, but there had to be a defusing period; otherwise the military would be releasing lethally trained human weapons into society. In our training, there has to be a balance that preserves our humanity.

In ancient China and Japan, the martial arts master was adept in other humane and artistic endeavors. Many practiced Chinese medicine. Some were masters of the tea ceremony. Many wrote poetry, were expert at flower arrangement or practiced calligraphy. Through these other endeavors they achieved balance in their lives. For this cause, the principles of Bushido were developed for the Samurai class ofJapan. It was like the chivalry of the Western knight. These philosophies and practices developed the humanitarian ideals in these warriors.

We can not train ourselves just to fight. That should be just a portion of our lives. When I was young, I swore that, ‘Karate was my life’. I’m glad that as I grew older, I expanded my expectations beyond the dojo. It’s true that the study of any real martial discipline should give one character. The demands that the study of the martial arts places on us, should serve to improve other areas of our lives. We should develop restraint, patience and discipline. The study of these arts should be a way of self improvement and discovery.

I am careful about what I teach and to whom. There are many techniques that are inherently dangerous and even lethal. I choose my students carefully. For this reason, I no longer have a commercial school. I don’t depend on teaching the arts for my livelihood. I went through a phase in my life when I had several schools and taught relatively large classes, but as my teachings became more combat oriented, I began to teach fewer students. I look for deep moral fiber and spirituality in any student that I teach. My classes are not religious class rooms, and I don’t demand that my students are all Christians, but if I don’t teach my beliefs by precept, I do so by example. In the end, my hopes are that they will be encouraged to follow in my spiritual path as well as in my martial way.

I will teach children the more classical arts, but the combative art that I advocate is geared towards adults. It also attracts more males than females. This isn’t so much because of the physical demands of the training, though I’m sure this has some bearing on it, but because of the nature of the techniques that I teach. Many are direct and radical in nature and some would be considered vicious. That kind of approach doesn’t appeal to many women. I teach modern weaponry as well as kobudo (the training in traditional weapons). I teach this, not so much for art as a means of self defense and personal protection. These are dangerous practices and weapons. For this reason, I feel a responsibility for the development of the character of my students. This is the new warrior way, or the Bushido of the modern Western warrior.

Any man can take a life. Untrained individuals do so every day. They may not do it with the grace that the trained martial artist could, but the end results are just as lethal. Men, speaking of the gender, are confrontational and aggressive by nature. The testosterone that infuses his system influences his tendencies towards violence and aggression. None of that has to be taught. If anything, it has to be controlled and curbed. If we followed our baser nature, most of us would end up in prison. We don’t train to become street fighters or bar room brawlers. We train to become better human beings.

Any man can exhibit aggression, but it takes more strength to nurture a relationship, comfort a child, encourage the elderly, and yes, to serve God. These are the higher callings of manhood. In truth, these are the higher calling in all humanity. This is the true source of any person’s strength. Lifting heavy weights doesn’t prove that you’re strong. Breaking bricks with your forehead doesn’t make one more of a man (I assume that most women have better sense than to engage in such practices). Growing, as human beings; seeking a closer relationship with family, friends, and loved ones, developing a closer walk with God; these attributes are the true makings of a man, or of a woman, for that matter. Undertake growth in these areas as you study your martial art. Develop your artistic side. Don’t be afraid of your tender nature. Be gentle, whenever allowed to be and forceful, when you have to be, but in all things, remain true to your humanitarian nature. Be true to God and to yourself. Seek the way of the warrior, not the way of anger, aggression and violence. Seek to be a decent human being as well as a trained warrior. This is Western Bushido. This is the ‘way of the warrior’.

Train hard, my martial arts Brethren, and go with God.

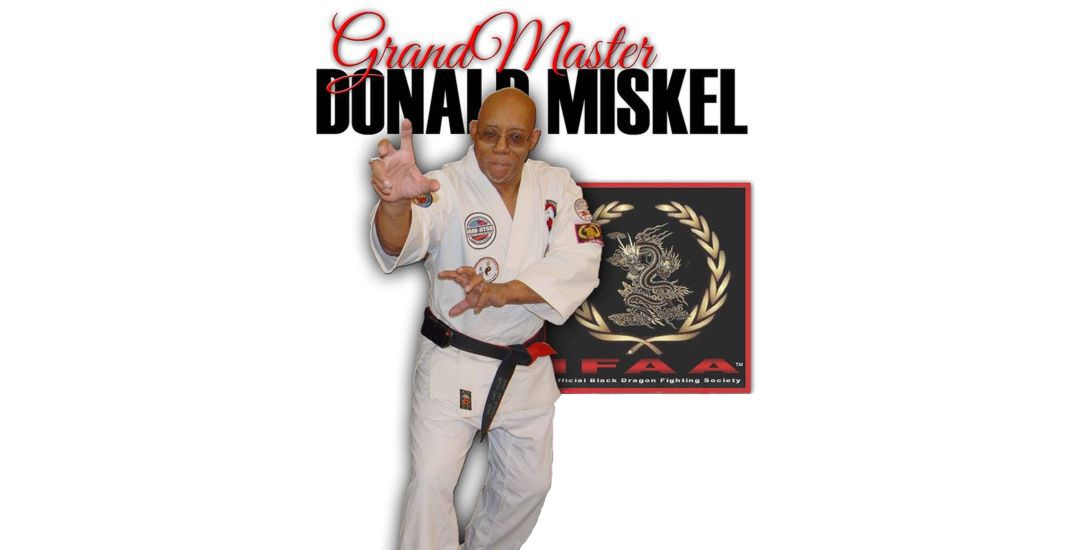

Dr. Donald Miskel