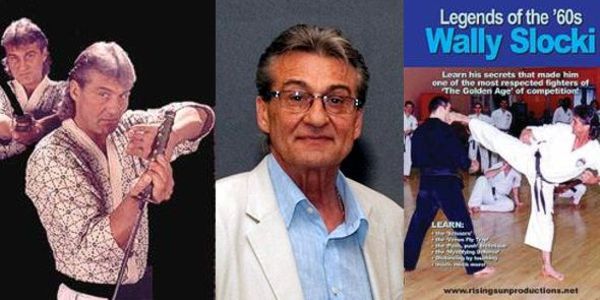

When Wally Slocki began teaching karate during the 60s, challengers occasionally sauntered into karate schools. They would grin derisively, size up the instructor, and ask him to fight. This happened to Wally Slocki several times.

When Wally Slocki began teaching karate during the 60s, challengers occasionally sauntered into karate schools. They would grin derisively, size up the instructor, and ask him to fight. This happened to Wally Slocki several times.

Instead of fighting his challengers, Slocki put them through an intense karate workout. They would take off their shoes and join him. The visitors looked awkward kicking in tight jeans. At first, they would kick and punch as hard as they could. But no matter how hard they worked, their moves seemed ineffective compared to Slocki’s.

Gradually, the challengers would slow down. Sweat would soak their clothing and drip off their forehead. When the challengers felt drained, Slocki would then ask if they wanted to spar. They would just look at him, say they’d come back later, and walk out, too tired to continue.

Wally Slocki took the fight out of his walk-in challengers without even touching them. He used the first principle of judo and karate: instead of opposing power head-on, exploit your opponent’s weakness. The way Slocki handled street challengers shows that he is not only a great fighter, but also a great thinker.

Wally Slocki started judo training at age 12 in Canada almost 40 years ago. In those days, the kids at school had never heard of judo. “What’s that, a food?” they asked. From judo, he took up kung fu and later Japanese karate. Slocki was one of the first in Canada to train in the martial arts.

During the 60s, he was one of the few Canadians who entered American karate tournaments. He sewed a Canadian flag to the back of his Gi top and was soon recognized at tournaments all over America as “the Canadian.”

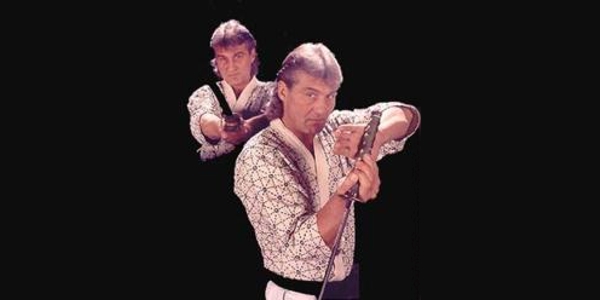

Wally Slocki was the 1967, 1968, and 1970 Canadian National Champion, retiring undefeated. He was the 1968, 1969, and 1970 Ontario Champion. He was also a top fighter in America. Tournament promoters flew him in to fight on the East Coast American team. Another time he was invited to join the West Coast team. “Anything to compete and have fun,” Slocki remembers.

“Wally Slocki was one of the two or three best fighters to ever come out of Canada, if not the best,” said Bob Wall. Yet when Slocki talks about the people he beat, he says he was lucky. When asked about his toughest fights, he said, “They were all tough.” His humility endears him to friends. I’d rather listen to you talk about yourself than he talk about himself,” said Wall.

In this vein, Slocki talked about the times he fought two great fighters and they each broke his nose. The first was in Kansas City, where he and Bill Wallace fought. Slocki had studied Wallace’s moves. He knew just how to counter Wallace’s fast left leg. I’ve got your timing now, Bill, Slocki thought.

In over-time, Wallace raised his left knee to kick, but Slocki rushed in to throw him. As he lifted Wallace, out of nowhere came a backfist. Blood spurted from Slocki’s nose, and the match was over. “Bill was sorry he banged me in the nose, but he wasn’t sorry he won,” Slocki said with a laugh.

In a 1970 demonstration match in Toronto, Slocki fought Joe Lewis. Between rounds, Lewis and Slocki looked at each other. Lewis pounded his gloved fists together and stared intently. As Slocki remembers, Lewis said, “I’m going to really hit you.”

“It’s supposed to be a demonstration match,” Slocki said. “What the hell’s going on?”

During the ensuing round, Lewis grabbed Slocki, kneed him in the head, and broke his nose. Blood gushed. Slocki didn’t laugh when he described this fight.

At one time, Slocki was rated number one in the world of full-contact karate. As the Four-Time North American Karate-Kung Fu champion, he eventually passed the crown to Billy Blanks and retired undefeated. He was the first to popularize the scissors kick. When an opponent blocked a high round kick, Slocki would take him down with the scissors kick.

After retiring from fighting, Slocki focused on teaching. In 1983 he started “Super Kids,” children’s karate centers that grew to 17 locations. He not only taught karate technique, but he also taught kids to out-think an attacker. Just as Slocki had defeated his walk-in challengers without touching them, he taught kids to avoid attack and to think one step ahead of the potential attacker. An example: if a child is confronted by someone driving a car, he should run away. But when at a safe distance, the child should write down the license plate number, and if he has no paper, to scratch the number in the dirt. Such training encourages children to think for themselves and to live without fear.

Wally Slocki continues to train, boxing several times a week. He teaches corporate stress management seminars, which is not surprising, because the martial arts leads to a relaxed way of life.

Students of Wally Slocki’s stress management seminars might never suspect that beneath his gentle manners lies a formidable fighter. “He never acted like a tough guy,” said Bob Wall. “But to me he comes out of the same mold as a Chuck Norris, or Jim Harrison, or Pat Burleson. They don’t have to tell you they’re tough. But they can show you.”