When I was a corrections officer working in the Costa Mesa Police Men’s Jail in 1990 a prisoner attacked me and ran me into a metal bunk bed trying to crack my skull open. After the fight was over and CSI took photos of my injuries, and my pain and anger diminished, I thought to myself, “This prisoner was a true fighter. He used the environment in his own cell to his own advantage. He knew exactly what he was doing when he shoved me. He used the bunk bed behind me as a weapon. Had I fallen back, landing just six inches lower, my head would have been split open by the metal bar of the bunk bed mattress frame. Bravo for him.”

Then the thought hit me as hard as that prisoner’s shove, “If criminals can use the environment as a weapon, then so can I.”

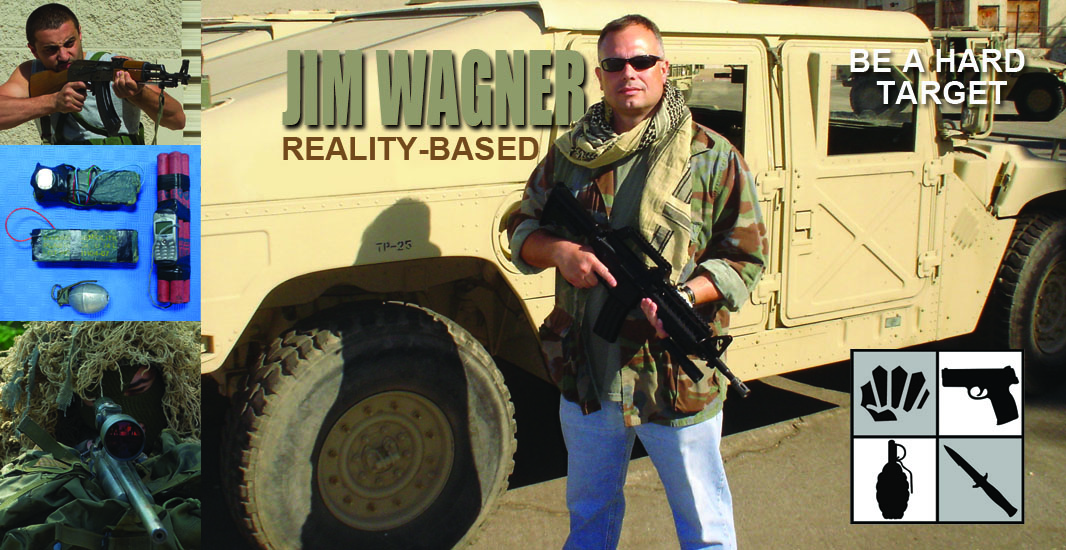

That moment of reflection, which is my learning process that always follows mortal combat, gave birth to the idea of an original self-defense training drill that I would eventually refine over time and train thousands of people in for years to come. To create a bit of trepidation I named the drill the Head Bouncing Drill and finally placed it into my Jim Wagner Reality-Based Personal Protection Level 1 Ground Survival course.

Just the name alone, when I mention it to my students as we come upon it in the outline, conjures up images of bloody lips and lumps on heads, and it very well could lead to that if it were not for my strict safety measures I have in place.

To run this drill I select two students. The minimum safety equipment each participant must wear is a hard shell Protec helmet, the type the U.S. Navy SEALs wear during maritime operations, wrap around eye protection, elbow and kneepads. Then I place the students in a corner; preferably with cement walls on both sides. If the facility that I am teaching at does not have a good corner to use inside the building, then I try to find a suitable corner outside.

I have one student go down on his hands and knees sideways to one wall, practically touching it with the side of his body, with his head pointed into the corner. This is a very awkward position, and it is meant to be. Nobody in a real fight would get in that position on their own, and so I must select the position for them. This is what I call a Position of Disadvantage. Real fights are fluid, and things happen instantly, like finding yourself in a bad situation because you slipped, made a mistake, or the opponent slammed you there. When I start a student off in a Position of Disadvantage then that is the beginning of a micro-scenario. A micro-scenario starts at a specific point in time and is stopped by the instructor for safety reasons or the objective of the drill has been achieved.

The second student participating in the Head Bouncing Drill is down on one knee next to the student who is on all fours. Once they are in place I explain the rules to them, as well as to the rest of the class who are all in a semi-circle around me and the first participants.

“When I yell out, ‘Go!’ you, the one on top, will try to smash your opponent’s head into the wall or into the ground. However, you on the bottom, in the Position of Disadvantage, you don’t have to take it. Oh no, in fact, I want you to try to get out of his grasp and do the same thing to him. Smash his head into the wall or the ground. Once, twice, or however many times it takes. Use the walls and the ground as a weapon.”

Both the participants and the observers look at me in horror. I don’t say anything for a few seconds to let their imaginations contemplate the worse. Once I see the affect has worked I head their fears off, “Of course we are going to do this safely. You are not going to run someone’s head through the wall or bounce someone’s head off the ground with full-force, but rather you are going to tap the helmet into the environmental weapon like this,” and I demonstrated with the student in the Position of Disadvantage by grasping his helmet with both of my hands and lightly pushing his head into the wall with two taps.

Everyone relaxes when they see and hear that the strikes to the wall are nothing to be concerned about. I justify the drill, “If you can tap lightly like this, then I know that in a real fight you are going to drive his head into the object. Adding the force later on is easy. Thinking about using the environment as a weapon is the hard part.”

After the first round, which usually lasts less than five or six seconds before someone’s helmet is tapping the wall like a woodpecker, I have them stay in the same roles, but then I’ll put the bottom student into a different Position of Disadvantage; usually sitting on their butt with their back in the corner. In a real fight this can easily happen when someone drives you into a corner and you are knocked down. Then, like the first round, I bark out, “Go!” and they try to get the upper hand on one another and hope they can produce the tapping sound I am listening for.

After two fights I have them switch rolls, and once again two different positions to fight out of. Occasionally someone goes a little too hard, or a helmet strap starts sliding off and chokes a student, and that is exactly why I am there to monitor the drill and stop it before anyone gets hurt. For the two decades plus that I have been doing this drill I have yet to have any injuries.

After everyone in the class has had the opportunity to go the Position of Disadvantage and the Position of Advantage, twice each, they are all in agreement that it is a drill that reprograms them to think about using the environment as a weapon in deadly force situations. They also agree that the drill is very unnerving when they head their own helmet hit the wall or ground, for they know that had it been done with full force they probably would have sustained a massive head injury.

For about two minutes I tell the story of the prisoner who attacked me in the jail by using his environment as a weapon and how his push gave me the idea to develop the Head Bouncing Drill

Be A Hard Target.