I learned what I know of focus, form and function in the dojo, but I learned to fight in the streets; in the nojo.

No, my friends, that wasn’t a typo. It isn’t a misspelling, though as many of you know I’m notorious for those, despite years of advanced education. If they gave belt levels in spelling I would never get past yellow belt. Thank God for spell check. Along with my questionable spelling ability, I can’t type. Not properly. I’m probably the fastest two finger typist in the Continental United States. I used to blame it on my wide hands and thick fingers. That, and the narrow computer keyboards. I did fine on manual typewriters. But, as I am often want to do, I digress (old folk are prone to ramble). This article is purposely called “Training in the nojo”.

Have you ever had one of those experiences that make you aware of your age? Several years ago, I happened to be in one of those mega department stores. I was living in Waukegan, Illinois at the time. The store was in the town of Zion, Illinois, one town over. I ran into a young man in his mid to early twenties. He asked me if I remembered him. Obviously, he was young. Any experienced person knows that you don’t ask that kind of question of anyone over fifty, and I was well over fifty at the time. I didn’t even pretend that I knew him. He smiled and refreshed my memory.

It turned out that he knew me from one of the neighborhoods where I had spent a good portion of my adult life. I had taught his father when he was a teen. I had a school at the time and I taught at the YMCA a couple of days a week. As a way of mentoring some of the kids in the neighborhood, I taught a karate class in the park on Saturday mornings. His father had been one of my students in those open air classes. When he had grown to adulthood and had children, he brought them to one of my schools for me to train. This young man had been my student for a year or two. I’ve taught more children than I can count over the years. Most I taught without charge. I remembered some of them but I had forgotten him. He asked me if I had a school in the area. At the time I was working and teaching classes at Chicago State University fifty miles from Waukegan. I had him bring his daughters to my house and I taught them basic self defense in my back yard. I actually managed to teach three generations of that family, all of them were under eighteen years of age at the time. That’s when I realized I really was getting old.

In my many years of teaching the martial arts, I have taught some of everywhere. I taught for the YMCA, in community centers, church gyms, Chicago Park District field houses, a couple of colleges and universities and in formal dojo. Of the places I have taught and trained in, my favorite place was in the nojo. No, that isn’t a proper word. It’s a play on words that implies training outside of the dojo. I’ve taught as many or more students in parks, back yards, garages and in whatever space was large enough to throw a kick or perform a throw in, than in gyms and dojo. On any number of occasions my wife has threatened my life for teaching impromptu classes in the dining room or having her living room smell like a men’s locker room.

I have owned a number of schools and at one time I owned several. I’ve also taught at schools owned by other sensei. All that was nice but the best classes I ever taught and my own best training were conducted in the nojo.

I grew up in the inner city; Chicago’s tough South Side. That’s a politically correct way of saying I grew up in the ghetto. Even after my father was able to move us out of those rough neighborhoods, I frequented the back alleys and side streets of the city. I was a street tough kid. I didn’t need martial arts for self defense. I was one of the problems that made martial arts necessary. I was one of the toughest kids in a rough neighborhood. Actually, my father, an ex marine, put me in a martial arts school to curb my aggression. I was prone to fight for any little reason. I was “gang related” very early on. Most of the guys in the hood were.

When I started taking karate, none of the other students wanted to train with me. I was accustomed to fighting. As far as I was concerned karate was fighting and that’s how I approached it. Because of the reluctance of the other students to train with me, I became my senseis’ uke, an excellent position for hands on tutoring, but a painful way to learn a martial art. Despite being a good fighter, I wasn’t necessarily a good karateka. I drove my sensei to distraction with my back alley approach to the arts. In order to move up in rank with the other students, I had to come to the school early and I was often there when my sensei locked the doors. I also had to spend a lot of time practicing at home. That meant in the park, the alley behind the apartment building or in the basement if the janitor left it unlocked. I got an old army duffel bag and filled it with old cloths. That was my heavy bag. I wrapped a two by four with hemp rope and surgical tape and made a makiwara. I bought, borrowed or stole every martial art book I could get my hands on. Most were old army manuals, since the martial arts weren’t popular at that time, and there weren’t many books available. Later, when eight millimeter films were available, I got hold of an old projector and acquired whatever martial arts training film I could find. I continue that trend till this day. I own an extensive martial arts library and my collection of martial arts DVDs number way into the hundreds.

I found out that I worked out better alone or with whatever poor unsuspecting kid I could finagle into working out with me. I taught the little I knew to other kids in the neighborhood, so I would have other people to work out with out side the dojo. Like me, these students were ghetto snipes and shared the same do or die attitude to anything combative. I practiced kata in the dojo, but because hard contact wasn’t allowed, I practiced my sparring in whatever available space me and my raged band of students were using for an impromptu gym. I wasn’t anywhere near instructor level but the students I taught were good at the violent style of sparring we indulged in. We literally beat the crap out of each other. Without the restraint taught in the dojo, these guys became the terror of the neighborhood.

I fought in a few tournaments but I didn’t care for them. They weren’t realistic enough for my liking and more often than not, I would get disqualified. Everyone could box in my neighborhood, even the girls. I boxed CYO and for the Chicago Park District for a couple of years. I was a good boxer, but boxing matches, like tournaments, had too many rules. I continued my own training methods and me and the guys I worked out with formed a renegade type of street kumite system that we called ‘Back Alley Ryu’. By this time, I was training with the infamous Count Dante (John Keehan). He was considered by the conservative martial arts community to be the bane of the martial arts world. I had found my niche. The training in the schools of his organization was grueling and brutal. I loved it, but it still wasn’t the same as training in the streets. I learned what I know of focus, form and function in the dojo, but I learned to fight in the streets; in the nojo.

When I was in the service I had an opportunity to see some of the full contact fights inThailand,Taiwanand in thePhilippines. I tried my hand at a few of them and got my can trashed. I earned my black belt in Kuntao and Chinese kempo (Chaun Fa) when I was in the service. Neither art was popular in the States when I got out of the service, and, while the organization I belonged to grudgingly recognized my rank, they never really accepted it. Besides I was growing in a different direction. I trained in other arts and went back to earn black belts in the jiu jitsu that I had studied in the early days of my martial arts career. During that time I fought in a few of the illegal pit fights that were cropping up in various places. Money was made from small purses and from side bets. The fights were brutal, but the fighters weren’t well trained, and while more realistic, they weren’t very challenging. I pursued more of my training in the backyard and garage dojo some of the returning GI’s were opening.

All of that was a long time ago. I’ve trained in quite a few martial art systems in my years in the arts. Some I’ve received advanced rank in. I’ve moved away from Chicago and lived in Tucson for eight years. In that time I have returned to my first love. Training in the nojo. The weather there is conducive to outdoor training if you can deal with the heat. I had a large backyard with a concrete patio. I conducted my classes outside in the years that I was there. It got hot, but it’s a wonderful way to train. I’m purchasing a new house and I’m converting a huge garage into a martial arts dojo. It’s large enough to hold all of my training and weight lifting equipment with room enough to train ten or fifteen students. This will be my new dojo.

In my years of teaching I have turned out some good students. Some were trained in the dojo and gyms that I taught in, but in my opinion, the best of them came up in my backyard schools. Many classical martial artists have criticized me for my love of informal training, but some of the greatest masters in history trained that way. The beautifully equipped gyms and dojo that we take for granted are a modern creation. Originally karate and jujitsu was taught in whatever space was available. The dojo was wherever the sensei happened to be teaching. Master Mas Oyama trained in the woods and in the mountains ofJapan. It was there that Kyokushinkai Karate was born. In the Philippines, Kali, Arnis and Escrima were generally taught in backyards or open fields. Pentjak Silat and Kuntao were basically taught out in the open. In this modern age, we have built beautiful and sometimes luxurious dojo, dojangs and kwoons but maybe we’ve lost something in the process. Teaching combative arts in luxurious surroundings may just take something out of the arts that we teach. I wonder if in those beautiful schools with their showers and sauna and nice locker rooms we haven’t lost the true essence of the combative arts. When I was in boot camp the surroundings were anything but luxurious. Luxury wasn’t conducive to our training.

I’m not suggesting that we close the doors of our schools and start teaching classes in the woods but maybe we should take a different approach to the arts. When I began in the arts the work outs were almost sadistic. Our sensei(s) and teachers did things to us that would get them sued today. Bloody noses, black eyes and split lips were expected and broken fingers and toes weren’t unusual. We beat on makiwara pads until our hands bled and our sensei were anything but gentle. I’m accused of being a tough teacher and many students wouldn’t put up with my type of training. I wouldn’t go back to the training methods from back in the day but I do believe that martial training should be just that; martial and combative in flavor.

Looking back, I still believe that I’ve become the martial artist that I am because of the way I trained. I wouldn’t want my students to grow up in the type of neighborhoods that I did, and I certainly wouldn’t want them to test their martial arts skill in hand to hand combat in some jungle or another. Many of us did though, and while I must admit that that’s a dangerous way to come by realistic fighting skill it’ll certainly slap you into reality. To many martial artists, their fighting skill is theoretical. They believe that what they’ve learned will work in a pinch. To those who have been there, there is no theory involved. Those who have had to face a knife wielding assailant or wrestle a fire arm from a determined attacker probably know what works and what doesn’t. The very fact that they are still in the land of the living says something about their martial abilities.

I am neither the consummate instructor, or martial artist, but I do know how to fight. I’ve been both shot and stabbed so my efforts weren’t always successful, but I managed to live through those experiences and learn from them. I’m not trying to present myself as super sensei. I have the rank but there are better practitioners and probably better instructors. What I am saying is this; you fight the way you train. If you don’t train hard you won’t fight hard. Fighting has to be based on skill and conditioning, but it also has to be based on experience and know how. If not your own, then from the person you train with. You can’t learn jungle warfare in a country club. By the same token you won’t learn alley fighting in a nice disciplined karate class. Learning to fight requires blood sweat and tears. Well, blood and sweat, anyway. Hopefully they will help you avoid the tears, at least in a real conflict. Cry in the class so that someone won’t end up crying over you in a funeral chapel.

Okay, I’m through pontificating. I’m climbing down from my soap box. Let me say this before I finish this rambling attempt at an essay. If you want to become capable as a martial artist, you have to challenge yourself beyond the comfort of the dojo. You have to train in different terrain. You have to take yourself out of your comfort zone. You’ll find that some of your most beneficial training will happen when you’re alone, away from your usual surroundings. Keep in mind that an attack won’t happen when expected or in a convenient place. If you expect the absolute worse case scenario you won’t be disappointed. You may have to defend yourself in a rocky alley, in a confined space or on ice or snow. Don’t confine yourself to the comfort of the gym. You can pretty much rest assured that you won’t be attacked there. Wherever you are when attacked is the nojo. Not a good experience, but if you survive it you’ll learn from it. In all truth, the only way to really learn to fight is to fight. Should you find your training thrust into one of those nojo situations leave the rules in the gym and please, no bowing before the conflict. There are no rules in the nojo. That type of thing may not be what you want to supplement your training, but should you find yourself in such a situation just consider it a (life and death) part of your training. This is where the hours of grueling training is put to the test. This is real life kumite in the nojo.

God bless you, my brethren. Train hard and train honestly. You never know when your training will go from the dojo to the nojo.

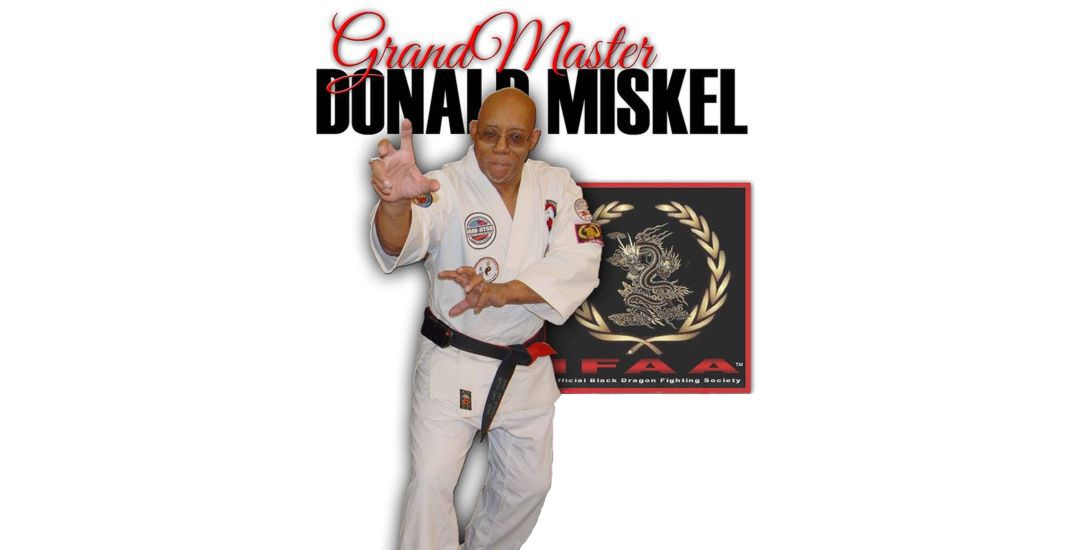

Dr. Donald Miskel