If you sit around chatting with instructors who teach in law enforcement, you will find a great deal of diversity on any training topic except one: working the fundamentals. Any top-notch instructor knows the fundamentals will always get you through. The challenge becomes identifying which technique to incorporate as a fundamental and which set of core techniques to focus on.

Take the stances we use in our everyday work life, for example. As street cops we can break down three major areas in which we use some type of stance: field interviewing, fighting (obtaining control), and shooting. Though we pay a great deal of attention to the techniques that flow in and out from the stance, we pay very little attention to the stance itself. Many police academies and law enforcement agencies have a variation for each of the three areas described. My question is why?

A DIFFERENT APPROACH

If you think in terms of body mechanics, your field interviewing, fighting, and shooting stances require that your upper body do different things, but your lower body more or less stays in the same position. The mission of each stance is to provide a stable platform from which to work. If you think about it in these terms, then you realize that most of the work is done by your shoulders and arms but the position of your hips and feet remains relatively unchanged unless you’re moving. Your body can be likened to a tank whose base stays the same but moves the turret and gun to engage the enemy.

Keep in mind that you need to use good tactics and strategy regardless of what stance you use. Appropriate distance, working angles, and good communication combine with and enhance the effectiveness of your stances. That being said, I believe that combining your field interviewing, fighting, and shooting stances into one basic platform makes much more sense than wasting time teaching multiple ones.

CLASSICAL SET OF STANCES

The classical interview stance involves your body being bladed 45 degrees to the suspect, your feet approximately shoulder width apart also bladed at 45 degrees, and your hands placed up above your gun belt in a non-fighting position. From this stance, you can switch into a fighting stance by either taking a step out with the lead leg or back with the

rear, depending on what martial philosophy you adhere to.

You also raise your hands up and cover your chest just under the chin. In this position both hands are ready to block, strike, or grab.

As for shooting, most officers use one of three stances: the Weaver, Isosceles, or Weaverese (combination of Weaver and Isosceles). Depending on where you obtained your training, the stances can be very different from each other and there is no nexus for consistency. A great deal of time and effort is wasted in learning multiple stances with little to no transition training or integration of other weapons or required skills.

THREE-IN-ONE STANCE

My idea is to combine the stance platform for use in field interviewing, fighting, and shooting. The basic stance is nothing new and has probably already been taught to you if you have attended an advanced pistol, advanced rifle, or a basic SWAT school. I learned the use of this basic platform in the early ’90s during my basic SWAT training. Though my SWAT days are long gone, I assure you that the basic principles behind the stance are as valid today as back then. It bolsters the argument that learning a small set of core skills well is much more important than being familiar with a larger set of skills.

THE BIGGEST ADVANTAGE TO THE THREE-IN-ONE STANCE IS THAT IT FOCUSES ON THE WAY THE BODY WORKS NATURALLY.

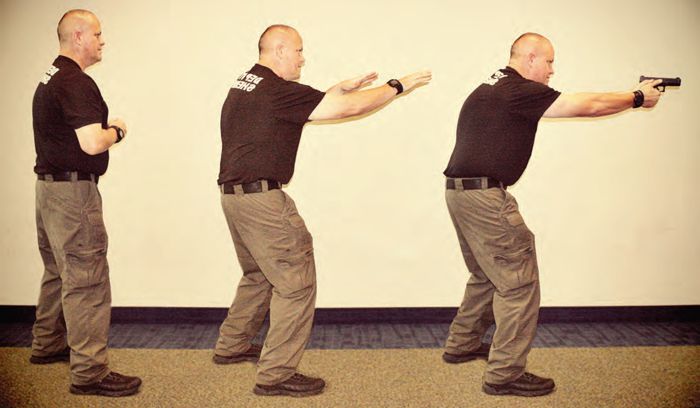

The biggest advantage to the three-in-one stance is that it focuses on the way the body works naturally. If you were to just stand naturally, you would find that your feet were around shoulder width apart and parallel to each other, similar to being on a smaller scale set of railroad tracks. Take a half-step back with your gun-side leg, bend slightly at the knees, and bring your hands up to the area of the middle of your chest in an interview position and you have a good idea of what the basic stance looks like.

Generally, the toes of your back foot are in line with the heel of your front foot, but the stance can be adjusted for personal preference and comfort. If you go too wide or too long, however, you will only alter the stance and render the same base concept useless.

Standing this way, you should take notice that you now have the most ballistic protection available from your body armor. Another selling point is that because the stance is patterned after the way you walk, it’s more comfortable and readies you for what comes next. No one walks at a 45-degree angle. Any SWAT operative will tell you that smooth is fast; this applies to stance work as well. The fewer adjustments or changes you have to make to get into your fighting or shooting platforms, the smoother you will become.

Transitioning from the interview stance into your fighting stance is a simple task. You merely bring your hands farther up, open with palms out, making sure your fingertips are under eye level (which ensures that your vision is not obscured). You establish a lead and back hand like any other fighting stance, which allows you to set up zones for each arm.

LEARNING ONE MULTI-PURPOSE STANCE

*The fundamentals will always get you through.

*Establish a small core set of skills that you can master.

*Take a look at consolidating your stances.

*Build one platform to handle field interviewing, fighting, and shooting.

*Using one stance will save time and money and enhance officer safety.

I don’t recommend closing your fists unless you need to. Once you close your fists you limit your tactical options by losing your ability to parry and grab. Also, if phone videos are recording and you have an open hand stance, it looks like you have taken a defensive posture vs. an aggressive one. The real issue is that if you make your hands into fists prematurely, you tend to tense your muscles in the arms and shoulder areas, expending valuable energy that you might need later.

As your lead hand is positioned forward and your gun hand is back, both of your elbows are resting close to your side. In that position, you can train yourself to cover your sidearm with your gun-side elbow. This creates a form of gun retention and allows you to feel if someone is grabbing for your weapon.

Transitioning to your shooting stance is simple. Draw your sidearm and assume an isosceles shooting stance, making sure you bend at the waist, roll the shoulders forward, and lock out your elbows. Because your feet and hip placement has stayed the same during your transition, you are ready to move in any direction in a tactical manner without having to adjust your stance first. By keeping the same base, the transition from interview to fighting to shooting and anything in between has been made much more efficient.

CONTINUITY OF TRAINING

Because of budget crunches and a lack of understanding, there is a trend among decision-makers to think in terms of saving time and money instead of thinking in terms of officer safety and survival. Therefore, it’s up to us to capitalize on every bit of available training time and see what we can consolidate by keeping what we need and getting rid of everything else. A skill not practiced is a skill not used when the need arises. We need to focus on core techniques that give us more bang for the buck.

By teaching one basic stance that officers can use under three different circumstances, an agency can save time and money, and enhance officer safety and survival all at the same time. It’s also a step in the right direction for the integration of skills and weapon platforms instead of thinking of them as different and separate.

An agency can easily sustain a standard level of consistency by first teaching this philosophy at the police academy, which is where officers start building their core skills. Once new officers come to an agency, they will reinforce the stance work during their field training. Lastly, the standard needs to be continued during in-service training. That way, by the time new officers complete their probationary period they are quite skilled at using the stance and it has either become second nature or is well on its way to becoming so.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Officers will learn to appreciate this one-stop shop concept as it becomes second nature. Since there is just one way to position the hips and place the feet, it’s easier to learn. Because the associated arm positions are natural, they add to, instead of interfering with, the stance. How you train is how you react; I find stance work no different than any other tactical training consideration.

The key to the three-in-one stance is that the bottom half of your body stays basically the same. The only thing that changes is your upper body, based on your situation. Your hands are either close to your chest, out in front ready to fight, or holding your sidearm ready to shoot. It makes life easier when you move, transition, and integrate other skills.

Play with it, modify it for your needs, and make it your own. I did, and it has served me well throughout my career.

Amaury Murgado is a special operations lieutenant with the Osceola County (Fla.) Sheriff’s Office. He is a retired master sergeant from the Army Reserve, has 25 years of law enforcement experience, and has been a lifelong student of martial arts.

Original Published in Police, October 2012