There is legend that states karate came to Okinawa in the nineteenth century when Chinto, a shipwrecked Chinese sailor, was washed ashore. Naked and penniless in a strange country, he hid in caves by day and at night would sneak into the villages to steal food for survival. The villagers complained to the king, who sent his best samurai, Matsumura, to capture the sailor.

Matsumura tracked Chinto to the cave where he was living; he confronted Chinto. When the sailor refused to surrender, the samurai tried to overcome him by force. Chinto blocked every technique Matsumura threw. The sailor then hid in a nearby cemetery.

Matsumura returned to the king and reported that there would be no more trouble from this man. Then he went back to the cemetery and befriended Chinto, who in turn, taught him his system, including the kata now known as Chinto.

Chotoku Kiyan, incorporated Chinto Kata into the Shorin-Ryu system. Kiyan, was the first sensei of Tatsuo Shimabuku, who is today Okinawa’s leading karate master. Shorin-Ryu features the Goju-Ryu system of his second sensei, Chojun Miyagi, in developing the present-day Okinawan system of Isshin-Ryu. Liberally translated, Isshin-Ryu means the one heart method. The name is apt, for Isshin-Ryu is the product of a life dedicated to Karate.

Master Tatsuo Shimabuku was born in Okinawa in 1906. he began his study of karate at the age of 8 when he walked some 12 miles to the neighboring village of Shuri to learn karate from his uncle. His uncle sent him home; obstinately he returned and was sent away several more times. His uncle finally gave in to his persistence and accepted him as a pupil.

For about four years sensei Shimabuku was privileged to study karate in the dojo of his uncle each day after completing the most menial domestic chores. Having achieved a certain degree of skill in Shurin-Ti karate, Master Shimabuku went on to formal training in Kobayshi-Ryu. He met Chotoku Kiyan, who was already famous throughout Okinawa and became one of that master’s leading pupils. He also studied with Chojun Miyagi and became his best student. The sensei did not feel he was old or experienced enough to be considered one of the greats at this time. He again took up Kobayshi-Ryu, this time under Choki Motobu, who was virtually a legend on Okinawa. At a large martial arts festival in the village of Fatima, sensei Shimabuku finally blossomed. He won recognition through a very fine performance of the katas.

Shimabuku went on to study the art of the bo and the sai as well as the tee-faa forms. His instructors, Hirara Shinken and Yaby Ku Mo Den were responsible for providing Okinawa’s instructors with these particular skills.

Shimabuku’s reputation throughout Okinawa had reached its peak when World War II struck the island. A business man as well as a karate teacher, the sensei’s small manufacturing plant was completely demolished and he was bankrupt almost from the war’s outset. He did his best to avoid conscription into the Japanese Army by escaping to the countryside where he worked as a farmer. As the situation grew more and more desperate for the Japanese and as the need to press the Okinawans into service became urgent, he was forced to flee.

As his reputation in karate spread among the Japanese, many soldiers began a thorough search as they wanted to study karate under him. The officers who finally caught up with him agreed to keep the secret of his whereabouts if he would teach them karate; it was in this manner that Shimabuku survived the war.

After the war, his business ruined a little chance of earning a living by teaching karate on the war-ravaged island, Master Shimabuku returned to farming and practiced karate privately for his own spiritual repose and physical exercise. Throughout Okinawa, he was recognized as the island’s leading practitioner of both Shorin-Ryu and Goju-Ryu Karate.

In the early nineteen fifties, the sensei began to consider the idea of combining the various styles into one standard system. He could foresee the problems that were developing out of the differences among styles; he sagely concluded that a unification or synthesis of styles would enhance the growth of karate.

He consulted with the aged masters on the island and with the heads of the leading schools. At first there was a general agreement, but later his idea met resistance as the leaders of the various schools began to fear loss of identity and position. Sensei Shimabuku decided to go ahead on his own; thus Isshin-Ryu karate was born.

In developing Isshin-Ryu, Master Shimabuku combined what he felt to be the best elements of Goju-Ryu and Shorin-Ryu, taking advantage also of the profound knowledge of Gung-Fu that he had acquired over the years. The basic katas derive from Shorin-Ryu and are common to most other styles of Okinawan karate. Most of the hand and foot katas are named after great Chinese karate masters.

The first kata a beginning student learns is Seisan, in which he learns a vertical punch with the thumb on top instead of the twist punch. The twist punch is prevalent in most other forms of Okinawan and Japanese karate. For several years, sensei Shimabuku taught the twist punch, to avoid controversy, but he returned to the vertical punch for several reasons; he felt it was faster and could be retracted more easily without elbow breaks. Further, the wrist tends to be stronger and focus need not be applied at the end of a twist while the arm is fully extended.

Kusanku, the sixth kata in Isshin-Ryu karate, emphasizes the speed movements for a man surrounded by eight attackers; it is a very beautiful kata. Sunsu, which is named after Master Shimabuku, consists of combinations of movements from the first six katas and is one of the most difficult in all karate to perform; that is, with any degree of strength, speed and accuracy. Sunsu, Master Shimabuku’s nickname means, “Strong Man”.

Weapons techniques are an integral part of Isshin-Ryu karate. Within a year, a new student will learn such katas as Kusanku Sai and Chata-Yara No Sai in which the sais are used to defend oneself against an imaginary samurai swordsman. In most all styles of karate the bo was handled strictly from the left side until sensei Shimabuku broke tradition and brought the right side into play. In the Urishi Bo kata, the opponent’s attention is drawn by the front of the bo until he is suddenly hit by the rear end of the bo which has been brought around with a vertical butt stroke. Another bo kata of the system is Tokumine No Kun No Dai named after Tokumine Kun, who virtually created the bo as it is known in modern karate.

In teaching karate, Master Shimabuku stresses striking with full force when the time to strike presents itself, and relaxing completely when at peace. He believes the student must have more than a short-term commitment to benefit from karate training. Isshin-Ryu karate instructors recognize four steps in the making of a first-rate karate man. The sensei likens it to woodwork.

The first step, Aakezuri, is like cleaning the bark off a rough tree. The student learns, according to his ability, some basic stances and moves. The second step, Nakakezuri, is like the shaping of wood. During this stage, the student demonstrates his seriousness and willingness to work learning the katas. Many are eliminated at this time. The third stage, Hosokezuri, is like the sanding and the molding of the wood. The student refines his technique and may achieve the rank of BlackBelt.

The final stage, Shiyagi, is like the smoothing and polishing of the wood. The student begins to understand in his own terms the Code of Karate, also called Kempo Gokui which means “Innermost Meaning.” This code, taken from Oriental literature and philosophy constitutes an attitude toward all of life and should be approached only after the student has learned all the kata and devoted the necessary time and practice to Karate Do.

Devotees of Isshin-Ryu karate are often asked about the emblem on their patch. It shows a woman who is half sea-serpent in a turbulent sea, her left hand in a universal sign of peace and her right hand clenched in a fist. A small dragon ascends in the dark night toward three stars in the heavens. The emblem represents a vision which came to Master Shimabuku in a dream he had during the time he was developing the Isshin-Ryu system. Feeling that is symbolically expressed what he was trying to accomplish in Isshin-Ryu karate, the Sensei adopted it as the emblem of his system. Those who wish to interpret the emblem further may find it interesting to know that Tatsuo, Master Shimabuku’s first name, means “Dragon Boy.”

Sensei Shimabuku has just named the goddess in the emblem in deference to pressure brought about from disciples of Isshin-Ryu karate. He named her Mitzu-Gami. With the ever expanding popularity of the Isshin-Ryu system, the goddess is assured a very long reign indeed.

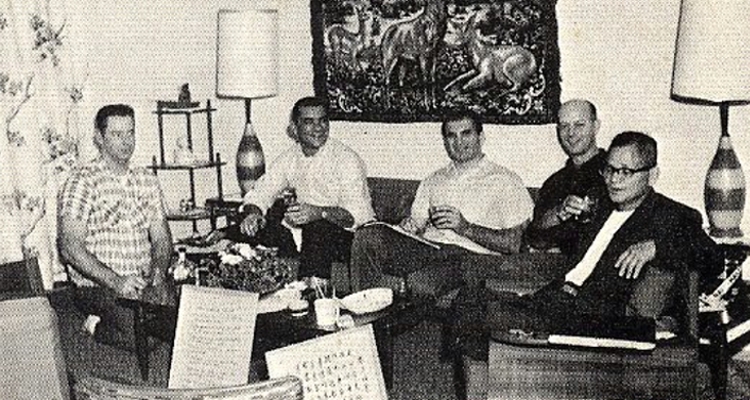

“From 1966 through 1968, Angi Uezu was in the United States. Mr. Uezi is the son-in-law of Tatsuo Shimabuku, 10th Dan, Master of the Isshin-Ryu system of karate. One of Mr. Uezu’s purposes in coming to the United States, was to help establish and create a better understanding of the origins of this traditional Okinawan system. Uezu traveled to many parts of the country helping many American senseis. After spending nearly two years in the United States, Uezu returned to Okinawa. Before his departure, however, he spent approximately one week in Los Angeles where I had the pleasure of working and talking with him. He helped to confirm some of the historical facts in this article,” states Bob Ozman.

This article was written by by Barry Steinburg, Bob Ozman and Steve Armstrong and it first appeared in Action Karate magazine Volume 2 Number 3 1969.