This series of articles explores the basics of “bunkai” (kata application). Over the last six parts we’ve been discussing the fundamentals of this vitally important aspect of karate. We’ve seen how the most common kata movements can be applied at close-range. We’ve also examined the key concepts of bunkai which, when understood, will allow you to understand kata. The Basics of Bunkai – Part 6, The Basics of Bunkai – Part 5, The Basics of Bunkai – Part 4, The Basics of Bunkai – Part 3, The Basics of Bunkai – Part 2 and The Basics of Bunkai – Part 1

In part six we looked at a couple of bunkai examples from Pinan Shodan / Heian Nidan. In part seven we are going to look at some bunkai examples from Yodan and Godan. The first three Pinan kata record the fundamentals of the fighting system recorded by the entire Pinan series. The final two kata build upon those fundamentals.

Once a certain skill level has been achieved it can be prudent to develop your understanding of the underlying principles, look at alternatives and add “supporting knowledge” to the basics. You always aim to use the basics in the first instance; no matter how “advanced” your knowledge. However, a deeper understanding of core concepts and the alternative ways in which they can be applied will make you a more versatile martial artist. I believe this is why the Pinan kata are structured in the way they are.

In part one of this series we saw how the “rising block” – as found in Pinan Nidan / Pinan Shodan – can counter an opponent securing a grip on your clothing. An alternative way to deal with this situation is found in Pinan Yodan. This secondary method can be used as an alternative or an addition to the core method shown earlier in the series (the first method can flow into this second one).

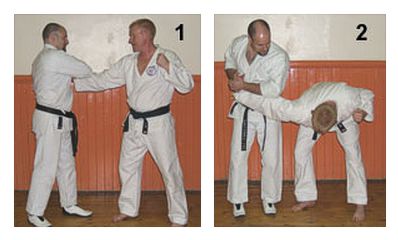

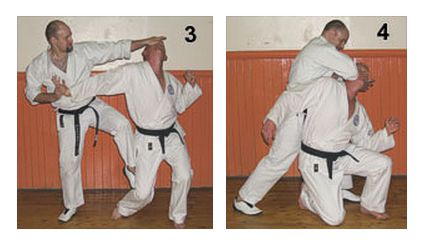

The opponent has seized your clothing. Deliver a strike before seizing the hand the opponent grabbed you with (Figure 1). Turn to the side and push down on the opponent’s elbow with your elbow (Figure 2). You’ll remember that in previous articles we covered how a movement performed to the side within the kata means you need to be sideways on to the opponent when applying that movement. Pull on the opponent’s hair as you deliver a kick to the opponent’s knee (Figure 3). Use your hand to control and create a datum as you deliver an elbow strike to the opponent’s jaw (Figure 4).

There are a few interesting bunkai concepts demonstrated by this sequence. The first thing to discuss is the height of the kick. In the kata the kick is performed at middle level; whereas the kick is delivered to the knees in the application. It is very common for the kicks to be performed at an elevated height in today’s kata. Whereas the kicks were originally performed low, a desire to “improve” the look of the kata and make them more athletically demanding has seen many kicks being performed higher. This can obviously cause inconsistencies when examining the application of a kata sequence. From a practical perspective, we never want to kick higher than mid-thigh. Keep this in mind when studying kata. Just because you may have been taught a version of the kata where the kicks are high, does not mean they were originally that high and it certainly does not mean that should be applied that way.

The second thing to note is that different styles perform a different kick at this point in the kata. Wado-Ryu and Shito-Ryu perform a front kick. Shotokan performs a side kick. When people discuss the differences in kata, they often assume that one version is correct and the other is flawed. However, when you look at the bunkai of any given sequence, it becomes apparent that the variations are frequently just different ways of achieving the same result. Does is matter if you take out the opponent’s knee with a side kick or a front kick? Both will work well and I therefore feel it is misguided to say one version is “wrong” and another is “right”. Bunkai study shows that all the various styles of karate have a great deal in common. The style differences are often little more than varying manifestations of common principles.

In the kata, a clenched fist is moved across as the kick is delivered (the “lower-block”). This represents grabbing the opponent’s hair in order to pull the head back and set them up for the elbow. In the photographs you’ll notice that’s not what I did. I hooked my thumb under the opponent’s nose and used that to move his head back. The reason I did that is that my partner’s hair is too short to secure a decent grip. I therefore adapted the movement but adhered to the key principle (use pain to position the opponent’s head) in order to set up the elbow strike.

Once the application of a given kata motion has been sufficiently practiced, the next stage of study is to examine the underlying concepts and the various ways in which they can be applied. That way, you can adapt the technique, in line with the constant underlying principles, to be relevant and applicable to the situation at hand.

Gichin Funakoshi (founder of Shotokan karate) had twenty key principles of karate. The eighteenth of these principles was “Always perform the kata exactly: Actual Combat is another matter”. This statement emphasises the importance of being able to adapt the kata relevant to the circumstances and not being shackled by the ritual of the formal kata. Choki Motobu also told us to understand the principles of the kata so that we can adapt it as required; as did Hironori Otsuka.

It can be useful to think of any technique demonstrated by the kata as an example used to illustrate a principle. It is the principle that is truly important and therefore kata are best understood as a record of principles as opposed to techniques. However, our study will always begin with the examination of the example. It is these basic examples that we have been discussing in this series. However, we need to understand where our bunkai study is headed.

Another thing to note about the sequence from Pinan / Heian Yodan is how one technique flows onto the next. These longer transitions are not seen in the earlier Pinan kata. As would be expected, Pinan / Heian Godan contains the longest transitions and we’ll now move on to look at one of those transitions.

In part four of this series of articles we saw how the “lower X-block” from Godan can be used to dislocate an opponent’s shoulder. We have now reached the point where it would be a good idea to examine the entire sequence.

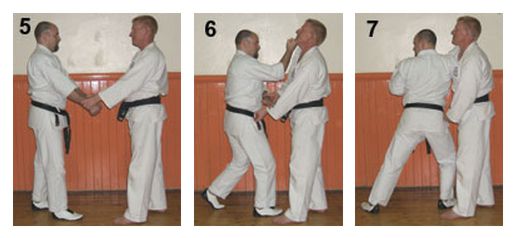

Your partner has seized both your wrists (Figure 5). Rotate your right hand and slap down on the inside on the partner’s wrist. This will free your hand and allow you to strike. Shifting forwards into reverse cat stance will add power to both your escape and strike. This is the application of the “reinforced block” (Figure 6). Tighten your grip on the partner’s right wrist as you feed your arm underneath their armpit in preparation for the following throw (Figure 7). This preparation is frequently mislabelled as a “rising punch”. This is obviously incorrect as you are looking in completely the wrong direction if it was indeed a punch. This is another good example of karateka seeing everything as “block, kick and punch”. However, as we’ve seen throughout this series, the original karate, as recorded in the kata, is much more holistic than the prevailing modern interpretation of the art.

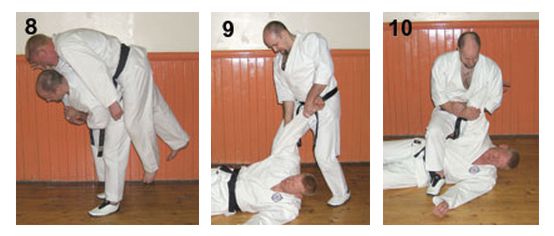

Execute a shoulder throw to take your partner to the floor (Figures 8 & 9). Once your partner is on the floor, apply a shoulder lock and throw your leg onto the other side of their body in order to prevent them twisting out of the lock (Figure 10). This is the application of the “lower x-block”. The exact details of how to apply this movement were covered in part four of this series.

This sequence from Pinan Godan is a transition drill across ranges and is not a “technique”. It can therefore be split into pieces to isolate specific skills, used as a drill to teach the flow of techniques, or can be adapted to include other throws, finishes, escapes etc. As before, the kata is giving us an example and we should not be afraid to vary that example and fully explore the underlying principles. It is when we do this that kata really starts to come alive. The sequence again shows how the Pinan / Heian series develops and how the later kata contain longer transitions.

I believe that kata should be viewed as a process. First we learn the kata. We then learn the applications of the kata. When the applications have been learnt, we should then start analysing the underlying principles and explore how to adapt the kata in line with those principles. This is still not enough though. We need to gain live experience of applying these techniques and principles otherwise all the knowledge gained from bunkai study will be theoretical and not practical. We therefore need to bring the methods of kata into our sparring.

Most modern karate sparring is based on the rules of karate competition, which is not related to the methods of the kata. To practice the methods of the kata we therefore need to engage in what I’ve termed “Kata-Based-Sparring”. This covers a broad range on non-compliant training methods that will include strikes, throws, locks, chokes, strangles, limb-control, etc. A detailed discussion on this training method is beyond the scope of these articles. However, as we said earlier, it is important that from the onset of your bunkai study you understand where the process is headed and what it will eventually involve.

The Basics of Bunkai Part 8 will be the final chapter in the Basic Bunkai series. In that article we will recap the key points of this series and summarize the information needed to unlock the kata and get you started with your bunkai study.