Steve Arneil was born in South Africa in 1934. At the age of 10, his family moved to Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), and he began training in Judo and boxing. His mother made him stop boxing, but he continued studying Judo.

From an early age, Steve Arneil was fascinated with the Orient, and he began watching a Chinese man practicing Shorin (Shaolin) Kempo in the man’s back yard. The Chinese man noticed Arneil “spying” on him, and invited him to train. Arneil accepted the offer and trained with his new friend throughout his school years and college.

Around the age of 25, Steve Arneil moved to Durban, South Africa, to complete his education in mechanical engineering. He found a local Judo dojo in Durban that also offered karate. At the time, a number of Japanese people were emigrating to South Africa, arriving at the port city of Durban. Steve Arneil would go to the arriving ships and ask if any of the Japanese practiced karate. If so, he would invite them to train at the dojo. These men practiced various karate styles, but Arneil didn’t care about the differences – to him, karate was karate.

After completing his engineering education, Steve Arneil went back home to Northern Rhodesia. Still fascinated with the Orient, he decided to go there and experience it for himself, and his Chinese friend gave him the names of people to train with in China. Fresh out of college and without any money, Arneil got a job as an engineer on a ship and worked his way from Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika (now Tanzania), to Kowloon, Hong Kong. From there, he went into China and traveled northward to the province of Manchuria, where he came to a monastery at which he studied Shorin (Shaolin) Kempo. The rigorous training, strict discipline, daily work in the monastery’s fields and daily meditation was just what Steve Arneil was looking for – he was in “seventh heaven.”

Unfortunately, China was beginning to experiencing Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, and life for a Westerner in China began to get difficult. People outside of the monastery even started hitting Steve Arneil on the head with their copies of Mao’s “Little Red Book”. His friends at the monastery suggested that he leave China for his own safety, and they brought him back to Kowloon to train with another kempo teacher. The training was very different than at the monastery, and Arneil didn’t like it.

Around that time, Steve Arneil heard of a karate master in Japan named Mas Oyama, and he was determined to go there and seek him out. He didn’t have enough money to get to Japan, so he first had to work on boats to the Philippines. When Arneil finally saved enough money, he returned to Hong Kong and from there went to Yokohama, Japan in 1961.

Initially, Steve Arneil was lost in Japan – he couldn’t speak the language and knew nothing about Japan other than the name of its capital. He somehow managed to get to Tokyo and found his way to the Kodokan, the headquarters of one of Japan’s styles of Judo. Arneil trained at the Kodokan for a short while and received the rank of Shodan (1st Dan) in Judo, but he was really interested in studying karate.

At first, Steve Arneil studied Goju Ryu karate under Gogen Yamaguchi. (Master Yamaguchi, who lived from 1909 to 1989, was also the instructor of Nei-Chu So, under whom Mas Oyama trained in the late 1940’s.) He trained in Shotokan karate as well, but still felt that something was missing.

Shortly after earning his Shodan in Judo, Steve Arneil met an American named Don Draeger and asked him if he knew of this karate master who “knocks bulls out.” Draeger did, and he took Arneil to Mas Oyama’s dojo. Arneil saw the intensity of the training and the discipline of the students, and he knew that this was where he wanted to be. Draeger (who was fluent in Japanese), asked the instructor if Arneil could train. The instructor told him that if he were interested, he would have to sit and watch, since Mas Oyama was in America at the time.

For about six weeks, Steve Arneil sat and watched, until one day Mas Oyama returned. Using Draeger as a translator, Mas Oyama told Arneil that he needed to come back and watch for a few more weeks in order to really make up his mind about joining the dojo. And so he waited and watched some more. After two weeks, Mas Oyama gave Arneil his first karate gi (uniform) and said that he would have to start from the beginning. He trained very hard, and even though he wasn’t Japanese, he was treated the same as the other kohai (juniors). They started training at 6:00 PM and couldn’t finish until Mas Oyama was finished, usually four or five hours later. Along with the other kohai, Arneil had to wash the dirty karate uniforms for the entire school and clean the dojo and its toilets – including emptying the toilet buckets.

When Steve Arneil tested for the rank of Shodan in Kyokushin Karate, he learned an important lesson in life from Mas Oyama. At the test, he thought that he did better than the others, but when the promotion list came out, his name wasn’t on it. No one told him why, and he became very upset and stayed away from the dojo for a few days. Finally, Mas Oyama came by and asked Arneil where he had been, and he responded that he had been sick. Arneil was depressed and wanted to leave Japan, but he didn’t have enough money to do so. Instead, he stuck it out and continued to train. At the next promotion test, Arneil lacked some confidence in himself, but he did what he had to do. When the promotion list came out, he was finally on it as a Shodan. Looking back on what happened, Arneil later realized that he wasn’t ready in his mind or heart when he first tested. If he had earned his Shodan the first time, he would have left Japan and moved on to something else, thinking that he had learned enough. Mas Oyama later told him that he saw more in Arneil than just a Black Belt, and he took the chance of losing his student through disappointment. Arneil’s initial failure eventually let him develop the patience, determination and perseverance (Osu) needed to master Kyokushin Karate.

Over the next few years, Steve Arneil intensified his training efforts and progressed rapidly. During this time, Mas Oyama became like a father to him. In fact, Mas Oyama actually adopted him so that he could marry a Japanese woman. With the financial support of his wife, who worked in a bank, Arneil was able to stay in Japan and train. To earn money, he also acted in some movies under the name “Steve Mansion”.

One day, Mas Oyama told Steve Arneil that he wanted him to perform the 100 man kumite (fight). Others had tried to do it, but no one (other than Mas Oyama) was able to complete all 100 fights. At first, Arneil thought that Mas Oyama was crazy for asking him, since he didn’t think he could do it. Mas Oyama kept pestering him until he finally agreed, and afterwards he trained fanatically for the event – 18 hours a day, every day, doing kata, makiwara (punching post) training and bag work. Arneil asked when he would do the fights, and Mas Oyama said that he would let him know when he was ready. Arneil kept on training, thinking that Mas Oyama had only done this in order to get him to train harder. One Sunday morning, he went to the dojo to train. When he walked in, everyone was there waiting for him. This was the day. At first, Arneil tried to keep track of how many fights he had completed, but stopped doing so after the first 20 in order to concentrate on fighting. He completed all 100 fights in about 2 hours and 45 minutes – “you can save time if you knock them out.”

Before leaving Japan in 1965, Steve Arneil had achieved the rank of Sandan (3rd Dan). He moved to Great Britain and began to teach Kyokushin Karate there. That same year, he and Shihan Bob Boulton founded the British Karate Kyokushinkai (BKK) organization. Between 1968 and 1976, Steve Arneil was the team manager and coach for the All Styles English and British Karate team, which became the first non-Japanese team to win the World Karate Championship in 1975-76. In 1975, the French Karate Federation also awarded him the title of the “World’s Best Coach.”

In 1991, Hanshi Arneil and the BKK resigned from the International Karate Organization (IKO), and he founded the International Federation of Karate (IFK). The IFK currently has a membership of over 120,000 in 19 countries. After the death of Mas Oyama in 1994 and the subsequent splintering of the IKO, Hanshi Arneil was asked by Mas Oyama’s widow to lead the IKO(2). Not wishing to become involved in the tangled politics of the various Japanese organizations, he politely declined the offer, in order to devote his time and efforts toward running the IFK and teaching Kyokushin Karate.

One of Hanshi Arneil’s goals in the IFK is consistency – every Kyokushin karateka in any country at any dojo should perform the techniques and katas the same. Toward that end, he has developed a systematic grading syllabus for the IFK and has published a book on Kyokushin kata. Mas Oyama had told him that the only way you can unify an organization is by doing the same thing, and the only way you can do the same thing is by kata.

Mas Oyama, prior to his death, personally awarded Hanshi Arneil with the rank of Shichidan (7th Dan). The entire British karate community later awarded him with the rank of Hachidan (8th Dan) for his dedication and services to karate in Great Britain. On May 26, 2001, the Board of Country Representatives of the IFK awarded Hanshi Arneil with the rank of Kudan (9th Dan) in recognition of his work in promoting Kyokushin Karate throughout the world during the past 40 years, and in particular during the past 10 years under the banner of the IFK.

While studying Kyokushin Karate in the early 1960’s, Hanshi Arneil took meticulous notes of what Mas Oyama taught him. Because of this, for the past four decades he has taught Kyokushin Karate true to the spirit of Sosai Mas Oyama. Despite his busy schedule as head of the IFK, Hanshi Arneil still teaches Kyokushin Karate – to beginners as well as Black Belts – on a regular basis.

In 1998, the USA-IFKK hosted Hanshi Arneil at the 8th Annual American International Karate Championships in Rochester, New York. In 2004, Hanshi traveled to the United States to lead the USA-IFKK Summer Training Camp. He returned in 2006 and in 2007 to lead the USA-IFKK’s Summer Training Camp.

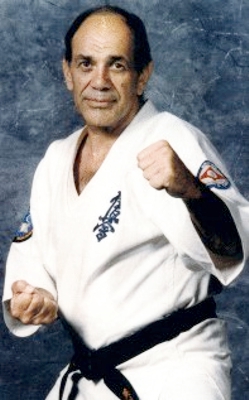

To contact the Honorable Master Steve Arneil and his International Federation of Karate visit the International Federation of Karate listing on the Martial Arts Schools and Businesses Directory by clicking on the image on the below.