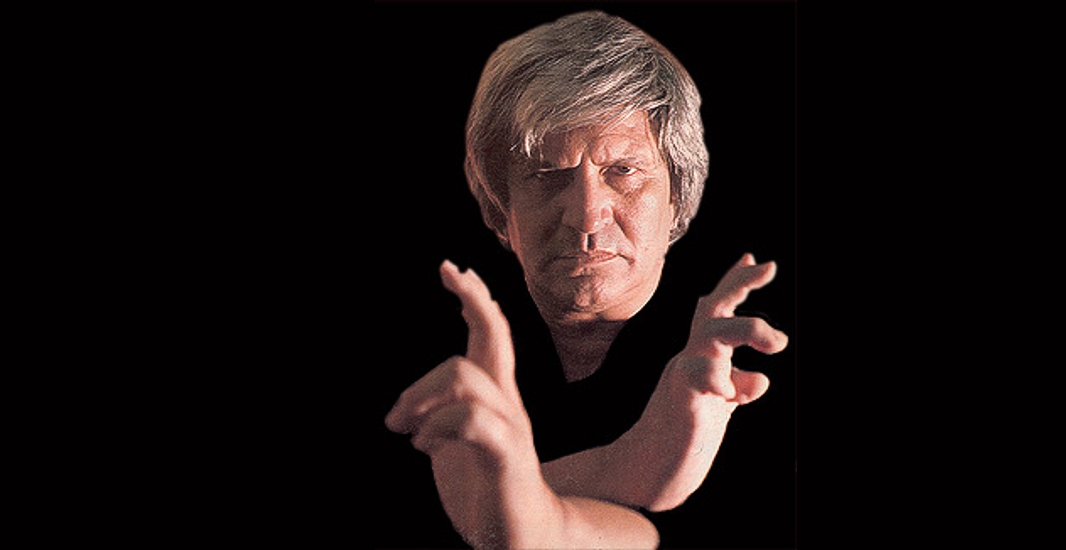

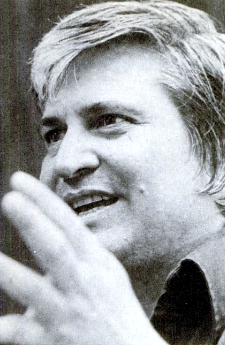

By John Corbett ~ He calls himself a magician of motion, and at 48 years of age he claims he has to be one just to persevere. But this self-proclaimed master of illusion pulls no rabbits from a hat. Instead, this martial artist, called by some the “Father of American Kenpo Karate,” has of late revealed to a few faithful followers the secrets of his fighting art.

By John Corbett ~ He calls himself a magician of motion, and at 48 years of age he claims he has to be one just to persevere. But this self-proclaimed master of illusion pulls no rabbits from a hat. Instead, this martial artist, called by some the “Father of American Kenpo Karate,” has of late revealed to a few faithful followers the secrets of his fighting art.

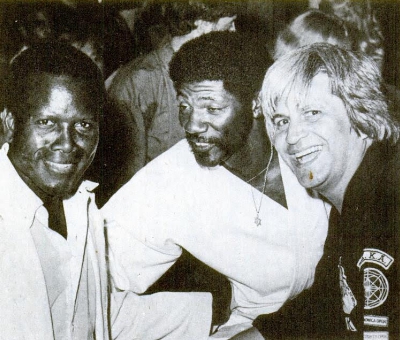

For illusionist Ed Parker, the magic which comprises his repertoire is no mere collection of cheap tricks, however. The magic of his art results from more than three decades of intense martial arts involvement in Hawaii as a student and in California (since 1956) as an instructor and promoter. He is known for his Long Beach International Karate Championships and as an instructor who awarded black belts to students such as Jay T. Will, Dan Inosanto and Jack Farr, all of whom have gone on to distinguished martial arts careers of their own.

Nevertheless, Parker has at times been denigrated as the teacher of a “slap art” in which the practitioner strikes himself as much as he does his opponent. But out of more than 30 years devoted to kenpo, Ed Parker has created much more than a mere “slap art.” Applying lessons from basic physics, geometry, philosophy, plus his Yankee-style common sense and youthful experiences in street scrapes in Hawaii, the big, graying but still agile Hawaiian has devised concepts he claims lie at the core of kenpo. He calls them his “master key movements” and the “alphabet” or “vocabulary of motion.”

To get to the core, however, the kenpoist applies a strategy that simultaneously makes his points and captures the interest of an audience to the same degree as a master storyteller or magician may when his material is novel. Parker, the storyteller relies in great measure on analogy and metaphor to emphasize the points he considers crucial in revealing the magic of his kenpo system, a diverse system he said he believes represents the cutting edge of martial arts advancement in the United States.

Although Parker may enthrall an audience during one of his frequent demonstrations or clinics, the kenpoist today said he remains just as excited over the potentialities of the martial arts as he did at his first introduction to the arts-in church.

Parker recalled a skinny and not particularly strong churchmate who bragged of whipping a bully because of his knowledge of the martial arts.

“He’s lying in church!” Parker said, exclaiming at the time. But he made a “convert” of Parker then and there with a quick show of technique. Impressed, Parker soon went to his churchmate’s brother, William Chow, and began his lifelong involvement with the martial arts.

After further studies with Chow and kenpoist James Mitose, Parker enrolled at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Provo, Utah, in 1949. His college studies interrupted by the Korean conflict and military service, Parker returned to BYU in 1954. While still a student, he began teaching kenpo at a local body-building gymnasium.

Parker completed his university work in 1956, made the move to California in 1956 and opened a school. Success fol- lowed. Parker soon franchised his school operations, and the martial artist retained a roster of some of Hollywood’s leading actors and actresses among his students. But for all the trappings of success, Parker maintains he found himself excluded from the mainstream of martial arts.

“I was a rebel,” the kenpoist insisted. “I was a misfit in the damn community in the martial arts world. Only now are they listening to what I have to say. That’s a fact.”

Martial artists and others are listening to what Parker says concerning the martial arts, however, for he said he travels an average of twice a month from his Pasadena, California, home, visiting teachers and providing demonstrations and conducting clinics. Parker remarked that his journeys are invaluable as a way for him to propagate his kenpo system and for his understanding of the development of martial arts overseas.

The kenpoist recalled a Chilean instructor who had studied under him in the United States more thar a decade ago.

“Arturo Petite stayed with me about seven or eight months, then invited me to go to Chile,” Parker said. “So, I went in 1968. At that time, he had around a hundred students.”

Parker said he gave a series.of demonstrations and offered clinics, not only for instructor Petite, but also at a naval base at Concepcion, a port facility south of Chile’s capital city, Santiago. The Hawaiian-born kenpoist remembered the rousing success of his demonstrations as he and local martial artists shared their expertise. Parker said the crowds “went wild” over his performances, not merely because of his skill but-and Parker stressed the point-also because the American gave the local martial artists a full measure of respect.

“I found out the reason was that they (the spectators) felt (my) acceptance,” he said. “Two or three months prior to that, a few Japanese envoys in the karate world watched their demonstration and criticized and condemned. That really got the Chileans mad. All they want is don’t (just) criticize the guy, correct him and tell him what he should be doing correctly .”

Parker said he found Chileans to be particularly wary of foreign martial artists who offer their individual styles to local students.

“There’s a guy who’s a commander in the Air Force, a guy named Commander Alvarado, and he’s in charge of deciding who does or does not come into Chile to teach,” Parker said. “They do have various styles, but they will not allow any group to come in and take over. They want them to come in for a period of time to disseminate any information and training that will enhance their people and that’s it.

“You can come and go. You’re not to reside and take over as has occurred in some of these other countries.”

Parker emphasized that at least partially one outcome of his Chilean sojourn was the marked success of Petite’s school, which he said now has “more than three thousand students and he’s doing very well.”

The kenpo stylist said he has found a similar desire for the locals to control the course of their martial arts programs in other countries in South America.

“That’s what they’re doing in South America,” he said. “Chile’s the only one that’s doing that (now), but all the other countries are starting to follow suit now, which I think is a great thing.

Even on a more recent trip to Europe in 1974, Parker said, he found the same attitudes.

“That was the big complaint of the Belgians that the Japanese were trying to take it over,” he said. ” All they wanted was for the Japanese to come in and teach them, but they wanted to control their own program and set forth their own rules and regulations.

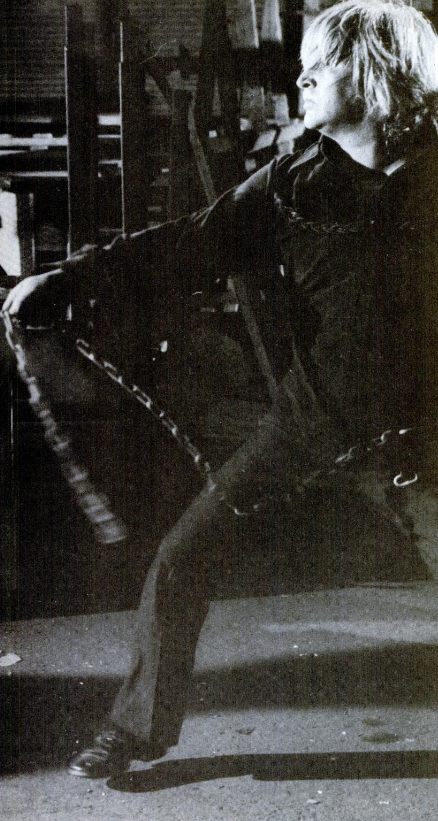

Out of these travels and talks with martial artists everywhere, Parker has developed his kenpo art and philosophy to a state where, with the help of analogy and metaphor, he has distilled certain essential points. First, he sees the techniques of his system three- dimensionally actually, as a series of planes or orbits revolving about the practitioner which enable him to fend off attacks from any angle and launch effective counterblows.

Pointing to a chart circumscribing a human figure, Parker said that “what you see here is only one-fifth the answer. Make five of these {around the figure of the man), then it will look like the structure of an atom. Therein lies answers I have to show you.”

Those answers he admitted have kept him and other kenpo instructors searching for a good while.

Those answers he admitted have kept him and other kenpo instructors searching for a good while.

“A lot of kenpo instructors are searching,” he said. “I’m not saying I have all the answers, but I haven’t stuck to tradition. When you stick to tradition, you’re bound. You’re bound to see only what is in that realm of knowledge.”

It is just this rejection of tradition that has led the kenpoist to the second secret of his system, a concept based on the age-old premise that the end justifies the means.

“When I teach, I want effects,” Parker said. “If a punch comes, if you block it and you look lazy, as long as you block it, that’s all care about. I don’t give a damn about going down with beautiful form.

“I was talking like this twenty years ago when I was a no-good-for-nothing rebel. I’m a street fighter. I’m a realist. I’ve seen guys go into a fight and bite {the other) guy’s nose off. And knowing that his nose is gone, he still hits! He’s an animal.

“What do you do for stuff like that?” he asked. “There’s nothing in the book. You know, on paper you can prove you can outrun a bullet, but would you like to try it? ”

For a person on the run, someone who must acquire a quick understanding of martial arts techniques, Parker said he has developed another concept.

“The secret of the martial arts is not to have knowledge of twenty-four things as it is knowing four things,” Parker said. “That is the key to all keys. It’s more important to learn four moves and the twenty-four ways in which you can rearrange them.”

Parker said if he can teach a student just four basic moves, there is then a total of twenty-four combinations in which those moves may be used. Increase the basic four moves to five, and the total of available combinations rises geometrically to 120.

“If I have a client who’s going to Europe, and he carries a lot of money, I will then gear my instructing to teaching him a condensed version but still master the key movements.”

“If I have a client who’s going to Europe, and he carries a lot of money, I will then gear my instructing to teaching him a condensed version but still master the key movements.”

This combining of specific moves to create a much larger vocabulary of techniques leads to Parker’s fourth secret.

“If I taught you the alphabet from ‘A’ to ‘G’ and then taught you how to arrange them to create words, there are a lot of words that can come out from, A ‘ to ‘G,’ ” the kenpo stylist explained. “Now, if we allow ourselves to use (the same letters) more than once, we can create even more words.”

Saying that this is as far as many martial arts go, Parker continued that many popular systems offer only a portion of the alphabet, only a portion of the vocabulary, of motion to students.

“That’s fine, that’s great,” he said. “But what about the additional letters of motion? You have to bring them into the picture. Then, your vocabulary of motion increases even more.

“Let’s put it this way” he said with emphasis, “everything from zero to nine is constant Everything after that is (a series of) combinations, and that’s the same thing with kenpo.”

Parker said mastery of as much of the vocabulary of motion was essential for instructors, for then, you can take out from your (instructor’s) mastery of knowledge those few movements that will work for that individual, knowing what his capabilities and limitations are.”

However, there were and are some masters of the martial arts who, even though they possess a remarkable vocabulary of motion, are not able to convey their knowledge to students adequately. Parker said he discussed the problem with Bruce Lee, whom he said he helped get a start in Hollywood.

“Bruce Lee, by the way, stayed here (at Parker’s house when he was) broke before I got him started in the industry,” Parker said. “He and I used to talk a lot. The kid was sharp. He was good. But he was one in two billion. For him to convey his thoughts and his style to another individual who lacked any quality that he had would never work.” Using another concept for comparison, Parker said he and Lee likened the entire body of martial arts knowledge to a mountain and that portion mastered by anyone man a piece of granite.

“He said that a man should be like a sculptor who gets a piece of granite and chips away the inessentials to get the true image of his imagination,” Parker said, continuing that he countered Lee’s comparison by asking the source of his granite.

“Lee retorted that to consider an entire mountain would lead to confusion,” Parker said, “but I said (to Lee) that’s not so. The instructor needs to know that mountain so that he can get that piece of granite (right) for that student.”

“And without further assistance from the instructor, the student would be in for further trouble,” Parker said he told Lee.

“Now it comes time for me to chip away the nonessential to get the true picture of my imagination. What do I see?”, asked Parker. “Raquel Welch. I chip away, and all of a sudden, I end up with Gravel Gertie because I have no talent. No matter how much I try, because of my lack of talent and skill, you cannot create that image.”

Parker reiterated his recollection of Lee’s inability to communicate his knowledge-of either the mountain or a piece of granite-to someone of less ability. And this is where Parker’s teaching comes in.

“He (Lee) felt that a lot of these things were nonessential,” Parker said, “nonessential to him at his level. I agreed – but not nonessential to the guy down here.”

Parker said he takes many pieces of granite, cuts them to size and assists his students in carving them; in other words, the kenpoist tailors his methods and techniques to suit the individual needs of his students.

“Many of us appear normal and/or alike,” Parker said, “but structurally, our muscles differ in size and strength. There is a definite need to adapt a system to the individual and not the individual to the system.”

The kenpo instructor said he will alter the timing of a combination of moves or of a technique with more than one specific move in it to fit the need of a student.

“Whichever one works best is the one I’ll pick,” he said. “If you really look at it, the underlying principle has not been changed or altered. It’s just the timing that has been altered.”

Parker admitted that many kenpo students appear more awkward than students of other styles-at first. He attributed the problem to the greater numbers of techniques which comprise his complete alphabet or vocabulary of motion.

“That’s the problem!” he said. “That’s why some of my guys at the early stages of learning look worse than a Shotokan student. I’ll admit that. But the Shotokan student, because of his limited knowledge, has more time, to work at it (techniques).”

No matter how many techniques a student may study, Parker emphasized the importance of the student’s understanding why moves are made certain ways.

No matter how many techniques a student may study, Parker emphasized the importance of the student’s understanding why moves are made certain ways.

“When learning English,” Parker said, “the alphabet forms the basis of our language. From them, words are created, phonetics added, pronunciation, along with definitions to give words meaning. I feel that over the years many students are going through their kata, but they don’t know what the kata are for.

“It’s just as if you and I were learning French,” he continued. “We say beautiful words just like a Frenchman, but we don’t know what the darned words meant. That’s idiotic!

“How can you place proper emphasis on kata if, in fact, you don’t know what they mean or know that a certain kata has more than one meaning?” he asked.

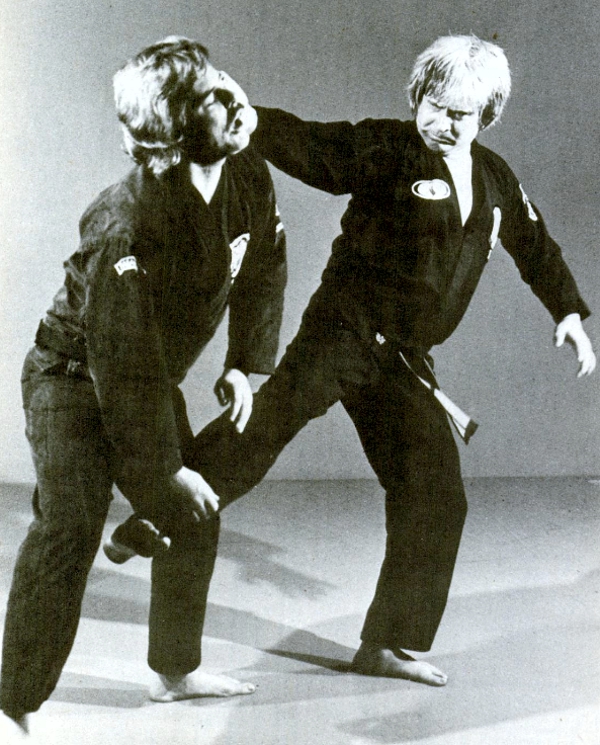

Parker said that a single move may be at one time purely defensive, then again, it may be a defensive move finishing as an offense, or the move may be used as a really aggressive technique. He gave as an example an arm thrown out above the head as an upper block. The kenpoist explained that the move may be used to thwart an overhead punch, later used for the same defense and then brought down against the opponent or used purely for offense. He admitted the precise positioning and timing of the move may be altered but insisted the basic technique remained the same.

“That’s like words that have one spelling having three or four definitions,” Parker said. “Can’t that also be true of motion? I found it to be true.”

Just as motion may have several aspects, Parker says he believes different points of view also are important to understanding and mastering the moves employed in kenpo.

“When I teach, I teach certain moves,” the instructor said, “and before that man leaves, I tell him what the possible defenses could be. I want him to see visually what he did and why he did it when he leaves. When he goes home, he will think about it.”

Parker said most martial artists concentrate on what they must do in a sparring or fighting situation.

“We never take the time to take his (the opponent’s) position to see what opening exist,” he said. ” At the time I’m executing a move, what could he hit back with? Also, could a spectator see an additional thing that could occur but you can’t because you’re too close to the subject?”

Yet another viewpoint seldom studied but which Parker values is motion reversed. “I studied my moves in reverse (on film), and then, lo and behold, all the answers came to me,” he said. “Motion is motion, going forward and reverse. Therein lie your answers.

“If a punch comes, I can parry before I elbow. Reverse the motion, I can use it not as a defense but as an offense. That’s how my vocabulary of motion increased tenfold.”

Corollary to the importance of taking in several viewpoints, Parker stressed what he terms his black dot concept. He explained that whereas many other systems utilize a white dot focus in which students concentrate all attention toward a target area, kenpoists focus on the black dot target and the peripheral white area as well.

“They (stylists who follow other systems) concentrate on maximum force or power, and very little thought is about defense,” he said. “But there are two things you’ve got to watch for -what a guy intends to do and what he does not intend to do.”

To explain, Parker brought up Newton’s theory of action and reaction, explaining that by devoting all attention on the attack-the white dot-the attacker may not notice what the opponent’s reaction is. He said this could prove dangerous by giving an opponent an unexpected opening. In another area, Parker again stressed the value of readiness.

“The one dirty word in my vocabulary is the word ‘and” he said “And to me is a commercial break. You can get nailed during a commercial. Don’t block and hit. Block with, no and. If you grab and twist, your face will get filled with a fist during the ‘and.’ ”

By drawing on philosophy, Newton geometry, the structure of the atom language and other concepts, Parker has developed a kenpo art and a teaching method of a very personal nature. He admits as much.

“Kenpo is the system I teach,” he said. “If, however, we were to examine my methods carefully, the system could very easily bear my name.” Though the system bears his stamp, the kenpo still gives credit where it is due. He is careful to note the source of his methods in the teachings of Jame Mitose and William Chow.

“If you look at my articles, I always give credit to him (Chow),” Parker said. “You have to remember that Chow has been belittled by a lot of people. He was the first person who started my thinking on our position regarding tradition.”

Parker also credited Chow for getting him to consider the notion of master key movements.

“Chow and I swapped a lot of information,” he said. “He noticed a lot of things didn’t work in an American environment. He was the guy who started me thinking about master key movements and increasing my knowledge.”

Parker explained that kenpo was not alone in undergoing modifications in the United States, at the expense of tradition and in favor of simplification.

“You find a lot of styles still stick rigidly to their particular kata,” he said, “but when you see them freestyle, they’re a different breed. They look like they’re from different schools. Each and everyone borrows like hell from each other.”

One may well ask, that with all the borrowing that occurs, would the individual styles, kenpo include, begin to lose their separate identities? Parker said he believes not.

“My art will not lose an identity because I have come up with concepts and principles nonexistent in other styles,” he claimed. “In other words, I feel the alphabet of motion is complete, most systems have only a small portion of the alphabet as opposed to the completed alphabet.”

Furthermore, Parker said he believes his system has much ‘to add to others.

“They’re going to have an American shotokan, an American gojuryu, because these principles and concepts can be adapted by anybody,” he said.

Parker admitted he had encountered problems along the way in gaining acceptance for his American kenpo system, problems revolving around an Oriental mystique.

“If you were Oriental, you were the in thing, ” he said. “If you were Caucasian, forget it!”

The kenpoist said his own inferiority complex was shattered during a visit to Japan. He said he found “the cream of the (martial arts) crop” were the ones who came to the United States.

“Those are the talented ones,” he said. “Little do we Americans realize it’s a small minority who we think is the majority .”

Parker quoted a passage from a book he is writing to elaborate his position:

Authenticity is said to be based on one having Oriental heritage,” the passage goes. But how false this belief is, for talent is not a gift given to a particular race of people but to individuals. It can be adopted, cultivated and perfected by an individual who least expects to be able to do so.

Many are gifted with the seeds of talent, regardless of race. Cultivation and effort is the stimulus that makes them blossom. On the other hand, although you can buy talent or have the talent to buy, it cannot be ingrained if you do not have the capacity to absorb it or execute it.

Another complex Parker has fought in propagating American kenpo is the twin concept of purity and tradition.

How often have I heard members of other systems explain that their system is a pure system,” Parker said with a sniff. “As if other systems were contaminated. ”

“What is pure?” he asked. “Everyone keeps talking about the fact that what Gichin Funakoshi taught is pure. Yet, if you go back and study history, you find he studied from two individuals. He put together what he thought were the best elements to be taught to the Japanese. How can you say his system is pure?

“I’m always told,” Parker said. “Well, here is a school directly from Japan. Their forms are authentic.’ I say that’s fine. But in actuality they’ve changed. That’s why you have shotokan and shudokan.

‘If you want to study boxing, then don’t study with Ali,” Parker said, drawing yet another of his analogies.”Don’t study with Norton. Try to get some guy who has preserved the John L. Sullivan methods of fighting. Stick to the classical. From an historical point, I agree. From a practical standpoint, I would never use it. That style isn’t what we’re looking for in the United States.”

Parker closed arguments on the purity controversy this way:

“My philosophy in answering this question is when pure knuckles meet pure flesh, you can’t get any purer than that, regardless of who executes the punch, no matter what style he may be from.”

Parker the realist nevertheless dresses up his demonstrations and explanations with a lode of analogies. In addition to those already noted, he compares kenpo methods with an eclectic array running the gamut from aircraft carriers to the three natural states in which water may be found.

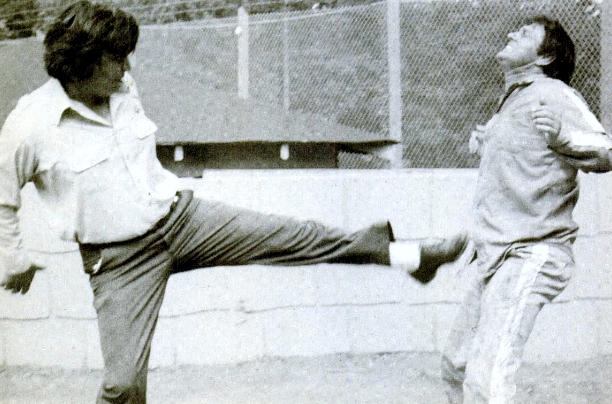

. . . Every time I put on a demonstration, I say it will be a little different from what the audience may be accustomed to,” he said, continuing that the emphasis is on sharing rather than showing. Parker said a kenpoist’s blow may be compared to the launching of an airplane from the deck of an aircraft carrier. The force of a punch in some karate is diminished by the practitioner’s pulling back with one fist while punching forward with the other.

“But if the lower half (of his body) is the catapult, the upper half is the force of my blow,” Parker said. “I then have the power and the force to keep this hand here (not pulling back as in Shotokan karate).”

Parker called his kenpo a gaseous martial art, not for all the talk that goes into describing the methods used, but because he said he sees its possibilities expanding in all directions at once.

“Water comes in three forms,” he said. “While people are at the liquid level, I’m at the gaseous stage in kenpo. When you have a solid, that’s it, a solid. When you have a liquid, it seeks its own level. But what does a gas seek? Its volume. That to me is the highest level of the martial arts. When I can go three or four directions at a time, that’s the highest state.”

By way of comparison, Parker called shotokan a solid-level martial art. He gives gojuryu and isshinryu styles a liquid rating. He does assent to hapkido’s gaseous state, “but there gas comes from one end basically the feet.”

Even Bruce Lee’s jeet kune do rates only a liquid grade from Parker.

“You have to remember about Bruce,” Parker said. “He could come in and not even know what you know, watch you, do a move he had no idea of doing before, come out and look just as good as you the first time out and better than you the second time around. That was his forte.”

For all his willingness to share his art with students at demonstrations and clinics worldwide, Parker said he is not a publicity seeker.

For all his willingness to share his art with students at demonstrations and clinics worldwide, Parker said he is not a publicity seeker.

“I’m not worried about publicity,” he said, admitting that his system had received lesser amounts of publicity than many others. “I’ve never called anybody to get me in. Many magazines have called me and asked me to talk to them, and I have refused, not because I’m antisocial. Many times, if you ask me what I’m doing, what I’m going to do, the minute I put it all down, people set up roadblocks. The less said, the more I can get done.”

“More” includes a book he said he put off completing when longtime student Elvis Presley died. But he said he is now ready to share his book and his knowledge.

“With what I have now, I’m going to just start to come out and hit heavy,” he said. “You guys came to me, fine. I’m glad to share my knowledge. What I’ve done, I’ve done. But I do care about what I’m going to do. I’m not going to tell you what I’m going to do. There’s a lot of jealous people out there.”

However, Parker did tell a detail or two regarding his book on kenpo-concepts, which have been included in this article. The kenpo stylist added that he will include a chapter on the relationships of the martial arts.

“To me, judo is a more ethical form of jujitsu,” he explained. ” Aikido is a more glorified version of jujitsu. However, all three could be considered an Oriental means of wrestling.

“Kenpo, karate, kung fu, tae kwon do and tang soo do are Oriental forms of boxing. But again, if you were to compare American boxing to the Oriental means of boxing, because of the limitations on weapons, we can say that American boxing is to checkers as what we do is to chess. The variables are greater . “But I would then say that kenpo is a three-dimensional chess game. It really is.”

Parker said he also plans a work on the subject of commonplace body movements and how they may be turned to one’s defensive advantage. Titled Everyday Gestures that Can Save Your Life, he said that even the most common movements opening or closing a swinging door, or using a hairbrush on long hair, may be used to advantage to thwart an attacker.

Parker admitted more than the fear of jealous rivals has motivated his reticence regarding his American kenpo. He said he has worried over former students who would leave and open up kenpo studios of their own.

“I always had the fear of guys taking off, being disloyal and opening up on their own,” he said. “And so I left out a lot of stuff.”

Parker said he found some students resenting his secretiveness, once they found out he had hidden knowledge from them. “They were somewhat hurt in a way ,” he admitted, “but they still feel happy. They are (the now-complete techniques) some minor additions in the whole puzzle. I am teaching those who stuck by me. The fact is, I was going to reserve it (the knowledge) for my children and my son. He’s not interested in the martial arts. He studies, but his heart is in the (fine) arts.”

In place of children lost as successors, Parker noted he has taken on proteges to insure the continuity of the kenpo system.

“My key protege is this kid Larry Tatum,” Parker said with a laugh, continuing that “anyone younger than me I call a kid. He’s my number one guy right now. He moves like me. He looks like me. He’s got the power-everything. ”

The kenpoist noted that he is helping 15-year student Tatum complete a book, Confidence, A Child’s First Weapon. He also named two others he considers proteges, insiders with whom he has shared the full scope of his knowledge, Tom Kelly, who Parker said is the highest-degree black belt at a seventh-degree level, operates a Parker school in Salt Lake City; Joe Palanzo, another formal student who Parker said holds a fifth degree black belt, teaches at a school in Baltimore.

In addition to his select protege, Parker insisted he will offer his kenpo edge to “anyone else who’s definitely sincere, because when I go to the grave I want to know that there are other people who (know) outside of my family. That would have the mountain of knowledge.”

Once he sees his students and proteges have the mountain securely within their grip, Parker said he will rest easy regarding the future of kenpo.

“I don’t see that once my students learn kenpo, they’ll modify it,” he said “They’ll perfect it. And that’s where they will excel.”

But again, the entire mountain will be too much for any one of them to grasp, according to the kenpoist. Each will call his own only “a portion of the whole-only that which suits each person.”

There will be enough to go around however. For Parker said he believes his system is more all-encompassing than any other at this point.

“It’s the most updated version of the martial arts, employing more concept and principles than in other art now,” he said. And though there may be a plethora of content available to students of kenpo, Parker said the real truth (their mastery of the art taken as a whole) may be gleaned in one fashion only.

“When it comes down to the end, Parker said, “what is true for one person may not be true for another. The real truth for both lies in the moment of actual combat.”

By John Corbett

Black Belt Magazine, July 1979