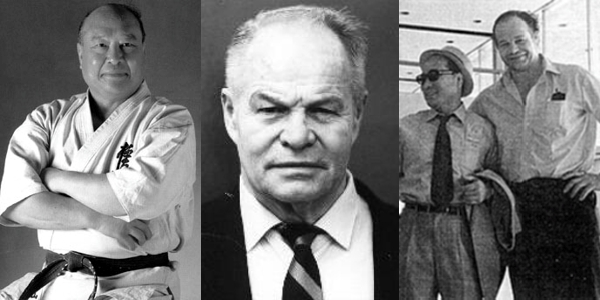

Mr. Mas Oyama amazed me with his feats of physical power, control, and speed, superhuman strength. This type of superhuman strength was not entirely new to me. I came from a part of the world that just naturally produced very strong men.

They were a gang of vicious streetfighters who liked to come into Greenwich Village on a Saturday night and pick a restaurant or club at random to terrorize. Tonight their Harley’s were parked in front of my Flamenco coffeehouse. Inside, the guitar was silent, and my waitresses and patrons were cowering, terrified. The street glittered with shards of glass from the brick the gang’s leader had thrown through the front window when the waitress protested their refusal to pay the bill. That was when my friend and I had walked in, fresh from six hours of training. Now we led them away from the coffeehouse, away from the lights and crowds of Bleecker Street and the eyes of any passing policeman, down a dark, narrow side street where the beef would be settled our way. As we walked the seven of them formed a rough circle around the two of us. The circle slowly tightened as they taunted us.

“Who the f–k are you, to tell us to get out?” growled their leader.

“I call the shots here. It’s my establishment,” I said calmly.

“Yeah? And who’s the dirty Jap?”

I glanced over at my friend, and our eyes met. His were long and black and gleamed like obsidian in the streetlight. Those who knew Masutatsu Oyama, or Mas Oyama, know the extraordinary power that leaped from his eyes. Most people’s eyes wander or turn cloudy as their thoughts wander. His eyes were lasers of pure, focused will. If you were a really stupid punk, like these guys, you might miss the catlike way he moved, or the hands as heavy as two stones, and think you were just looking at a stocky Oriental man of average height. But I couldn’t believe they didn’t see the danger in his eyes.

The gang’s leader reached under his motorcycle jacket and began to unwind a heavy chain from around his waist. Another one swung a thick two-by-four through the air and dragged it along the bars of an iron fence with a clanking noise. They might be stupid, but they were bloodthirsty, too, taking courage from their number and the alcohol in their veins. Taking two unarmed men, they thought, would be easy.

They didn’t know which two men they were dealing with.

I had a bad reputation as a streetfighter myself. Not only was I six foot two and a half inches and about two hundred twenty pounds, a former pro heavyweight fighter known for first-round knockouts, but I could go crazy if some loudmouth or bully challenged me and I knew right was on my side. A couple of the local gangsters had once seen me tear the flesh off a man’s face with my bare hands, and crush another one’s chest with my heel. After that they said I was a “made” man, one who had proven himself and should be feared and respected. I knew that a force greater than human can come roaring through a human body in great danger or rage. But the secret Mas Oyama had mastered, what I so marveled at in him, was the ability to call on that force at will and focus it precisely. I had raw power, but he had supreme control.

Whut! Whut! Whut! The leader was swinging his chain in a deadly circle, closer and closer to Kancho (as I called him). I saw him set himself to meet it, calm and unafraid. I felt so lucky. He was the strongest man in the world, and he was my friend.

I couldn’t help myself, I threw back my head and howled out with the joy of battle.

When I met Mas Oyama, an empty place in my life was filled. I had once had another friend I thought must be the strongest man in the world. His name was Omar, and when we were prisoners slaving together in the coal mines of the Soviet Union, he had saved my life.

That was in 1947, when I was eighteen and Omar was nineteen. Soon after, I had escaped from Russia alone, and gradually made my way to Canada to work on a logging railroad and then to the United States as a pro heavyweight fighter. By 1960, when Kancho would come into my life, I was a successful businessman, the owner of two thriving coffeehouses in New York’s bohemian Greenwich Village, Café Flamenco and El Gitano (“The Gypsy”), featuring folk music and authentic Spanish Flamenco. Like any strong personality I was surrounded by well-wishers and ill-wishers, rivals and hangers-on, and even a few good friends, but no one who filled the space left by Omar. He had been as close as a brother and more than my equal, and I did not know whether he was dead or alive.

No one ever thinks of the strong as lonely.

What I could never show or express, Flamenco howled out for me. I loved its basic, primitive quality. It came from deep in the belly, usually a hungry belly since the Gypsies who created it had nothing but their passions. One of my friends was an eccentric Flamenco guitarist named Augustino De Mello. One night in my coffeehouse, Augustino could not stop raving about his new discovery: Karate. “Look at this,” he said, and he showed me a book titled What is Karate? On the cover a man was defeating a charging bull with his bare hands. That man had written the book, Augustino told me. His name was Masutatsu Oyama or Mas Oyama.

Did I want to borrow the book? Augustino asked. Having been a boxer by profession and a streetfighter by necessity, of course I was interested in a book on fighting technique. But when I got it home, I discovered that it was much, much more. You couldn’t just write a book like that, you had to live it. This was a book I had to own. I went right out and bought a copy for myself. (I still have it.)

Mr. Mas Oyama amazed me with his feats of physical power, control, and speed, superhuman strength. This type of superhuman strength was not entirely new to me. I came from a part of the world that just naturally produced very strong men. During World War I, my own father and a fellow soldier had lifted and moved an iron cannon weighing over 600kg. In Russia, as skinny and starved as I was, I could lift and carry over 200 kg, and as you will see, Omar was much stronger than me. After the war I had seen a refugee from Yugoslavia crush a raw potato in his fist, the watery pulp oozing out between his fingers. So breaking bricks and stones barehanded was something I could imagine (and indeed, would soon do). But human nature is much harder to break. What impressed me most of all was the long time Mr. Mas Oyama had spent alone in the mountains, training. I knew of solitude; I knew the tremendous determination that took. I had decided to escape from Russia alone, under conditions a rational person would call impossible. Once I started, I had no choice but to go on or die. The several weeks it took me to reach freedom seemed like an eternity. Yet Mr. Mas Oyama had deliberately isolated himself from society for fifteen months, subjecting himself to severe hardship and deprivation in order to become strong. That a human being would do that voluntarily, and have the will power to stick with it, was awesome to me.

And now, Augustino told me, this man was coming to New York!

It’s hard to believe now, but at that time, karate was almost completely unknown in the United States. I myself, a fighter by trade, had only vaguely heard of it. Only a few Marines who had been stationed on Okinawa were familiar with the art, and even fewer had actually studied it. Mas Oyama had made up his mind to change all that. He had already come to America once, knowing almost no one and no English, to demonstrate the power of karate. Now his book had been translated into English, and my friend Augustino was one of the Americans who had written to him in response. Mr. Mas Oyama had answered his letter, saying that he was planning another trip to the States. Augustino asked me if I would like to come with him to meet Mr. Mas Oyama. I must have gaped at him with my mouth open. Would I like to? How could he ask such a question? There was only one answer: When and where?

The day arrived. We were to meet Mas Oyama at the New Yorker Hotel, right near the famous fight venue, Madison Square Garden, on a Sunday afternoon at three o’clock. In our eagerness we arrived ten minutes early. The moment we walked into the lobby I saw him. He was wearing dark glasses, but the aura around him was so magnetic I just knew it was him. He recognized us, too. He took his sunglasses off and reached out his hand. I shook it — it was heavy as a rock. There was that broad strong hard kind face, very handsome, and shining black eyes that seemed to pierce to the truth of the person in front of him. He was not very tall, but broad and solid, and he exuded power.

The strange thing was that though we could hardly speak to each other, we understood each other right away. Augustino, who was not a fighter, but more of an intellectual, sort of faded into the background. That first day I took Kancho to Chinatown to eat; it would become our daily habit. After one night in the hotel, he came to stay with me. Except for occasional visits to Brooklyn, where he had a student who had served in the U.S. military in Japan, Kancho would sleep on my couch for most of the six or seven months he stayed in the U.S. I had been starving for such company.

Of course I wanted to train with Mas Oyama, to learn from him, but I did not know how to ask. Kancho solved that problem for me within two or three days of his arrival. I had found us an interpreter, a Japanese college student named Yoshi, who was fluent in English and agreed to join us for a few hours every afternoon so we could talk. I will never forget, we were sitting in a Chinese restaurant the first time Yoshi joined us. Kancho looked at me, and the very first question he asked was, “Where can we train?”

An hour later, I had begun my first training session with the foremost karate authority in the world.

We were in a nice clean gym ten minutes from my apartment, which we called “the dojo” from then on. As that first training progressed, I saw sweat break out on Kancho’s face — and pleasure. To my great relief he seemed satisfied with his new student — me — even though the new movements felt awkward to me, so different from boxing. The dogi had long pants, and I was not used to that. At first it felt like it got in my way. Before long, I would feel naked without it.

Our first few workouts were two hours long, but soon they stretched out to three hours, then four. After two weeks we were training nonstop five to six hours a day. It was a regimen of endless repetitions, for Kancho’s belief was, “In repetition lies strength.” But it was far from mere repetition. Into each punch, each kick, you put everything you had. It reminded me of escaping from Russia — with one major difference: Kancho and I could go to Chinatown afterwards and fill ourselves with good food! But there was a similarity: when you are totally exhausted, and you feel you can’t go on, that’s when you reach down deep into yourself for more. You concentrate totally on each punch, each step, and then one more, and then one more, and then one more. Running for your life is not the same as choosing to train to your limits and beyond, but I understood that Kancho’s lonely training had honed the same kind of determination that had kept me alive.

Of course I knew more about Kancho, from reading his book, than he knew about me. I had showed him the scars on my legs, but I couldn’t explain how I had gotten them. Even when our interpreter Yoshi was there, about such things one does not speak much. Kancho, too, had written of his mountain training in a few simple words, but if you had imagination, they spoke volumes. Very few people knew that I had also written the story of my two years as a prisoner in Russia and my escape — the story you are about to read. I would have liked to give Kancho this book to speak for me. But my story was then just a manuscript; it was not yet published. And even if it had been, of course Kancho couldn’t read English. Still, by training together, we understood each other better than words.

I remember moving forward five steps, a punch with each step, then turning, and five steps back. Forward . . . punch and kiai . . . turn . . . step and punch back. Back and forth. Back and forth. Back and forth. . . . I got blisters on the balls of my feet, and they broke, and the water came out. I showed them to Kancho. He just smiled and rumbled, “Goooood!” Sometimes he would say “Today special day,” and then we would repeat just one technique, such as jodan tsuki, for forty-five minutes. Kancho would fall into a rhythm like a machine, a tireless, unstoppable machine. Afterwards, out of breath, I asked him “How many?” and he wrote on a blackboard at the back of the dojo, “5000.” I had always felt strong, but training with him, I felt stronger and stronger. And I could feel the hard training welding this new friendship closer and tighter.

When we finished training we would go to my apartment and shower. In the evening our translator Yoshi joined us in Chinatown, and we ate together and talked. Little by little Kancho was learning English. (In later years he would always have a translator present when a foreign branch chief or dignitary talked to him; unknown to the visitor, however, Kancho understood most of what was said in English, and while it was being translated into Japanese, he was already crafting his reply.) He was surprised that I knew how to eat with chopsticks, and I told him that when I was training as a fighter in Montréal I had lived with a Chinese restaurateur named Harry Fong, paying for my room and board by washing dishes.

One evening a folksinger was performing in my coffeehouse, and Kancho asked for his guitar! To my surprise, he started playing and singing with great sensitivity, a strong, sad song. Through Yoshi, Kancho later explained to me that it was the tale of a Korean farmer, his never-ending work in the fields and his family. I stared at Kancho’s hands. What strength they had, and yet how finely they handled the guitar! I wondered what other surprises he had in store for me.

BAM!!

The punch met the center of my chest with terrifying power. It was like getting hit by a subway train. For a moment I saw double as I struggled for the next breath. Of course, this was only kumite, our first sparring bout, and Kancho was controlling himself. I could only imagine what it was like to be on the receiving end of his full power. Since I loved life, I had no wish to find out.

There are a couple of myths I have to dispel about my friendship with Kancho, later Sosai, Oyama, even if the truth disappoints you. We’ve all seen so many Hollywood and Hong Kong action movies, the expectation of constant explosions, fights and chases has spoiled us for the sometimes more subtle drama of real life. One of those myths is that Kancho and I must have fought each other to a bloody standstill before we could become friends. I find it much more amazing that we somehow recognized each other at first sight. It’s macho nonsense that two strong men can’t be friends until they’ve brawled like tomcats, found out who is stronger, and earned each other’s respect. I had to earn Kancho’s respect, no question, but I did it through training with him, my great respect for him, and simply who I was. When it came to kumite, we certainly tested each other, and felt each other’s strength, but we had no need to find out who could beat whom in a real fight. (We both knew: he would win, but not easily.) I could tell he enjoyed our kumite, because with me, unlike most sparring partners, he could open up and not be afraid to do damage.

When I had first become a boxer, I couldn’t believe my luck. They wanted to pay me good money to go in a ring and hit somebody! That was just doing what came naturally. After what I had survived, I had no fear at all of getting hit, especially by fists with big pillows on them. And so I won 17 of my 19 fights, 15 of them by knockout, most of those in the first or second round. A little like Mike Tyson, I tended to overwhelm an opponent early with my lack of civilized inhibition and crazy fearlessness. Also like Tyson, I had to learn that raw power was not enough — it needs art, strategy and technique. As I sparred with Kancho my mind went back to my first big loss, the fight that first taught me that lesson.

At the time I had fought only three fights in Chicago, which was second only to New York in importance in the fight game. I had fought mostly in Minneapolis/ St. Paul, the hometown of my manager. So he was under pressure to show what I could do in a ten-rounder at Marigold Gardens or even the Chicago Stadium.

He got me a fight with a black heavyweight named Don Jackson. The truth was, I wasn’t ready for him. He was a far more experienced fighter than I was, with about 90 amateur fights and 25 pro fights already under his belt. But I trained hard, I got into the ring with him . . . and I just couldn’t get going. Jackson was too fast; he was all over me. No matter how many times he landed his fast, stunning jab, he couldn’t knock me off my feet. But he won by TKO, technical knockout.

After that I fought two more big heavyweights in Chicago, and I knocked both of them out in the first round. One of them was a tall, rangy Texan named Bob Thorne, whom I instantly liked and respected. I remember thinking that fighting was a stupid game, where you had to try and hurt a man you’d rather be friends with. But I did it. I still regret it. Then my manager arranged a rematch for me with Don Jackson, a ten-rounder in Minneapolis. I trained very hard, and my trainer, who had watched and studied the first fight, told my sparring partners what to do. They were to jab and jab and throw right hands at my chin. I, in turn, was to wait for the stiff jab, and when it came, brush it aside, lean in and hook a hard left into his gut, and then let loose my right hand. I trained as if I was possessed.

The day of the fight came. The arena was packed. A lot of people from Chicago had come to Minneapolis just to see the return bout, and some big money men, friends of my manager from New York City, were also in the audience. At the weigh-in Don Jackson was a little condescending to me. I hoped that would soon be straightened out. Finally we were in the ring alone together, just him and me. Jackson looked at me and grinned as if this would be a replay. The introductions ended, the bell sounded, and the fight was on.

Jackson came out of his corner dancing, and he began flicking jabs at me. I just shuffled after him. He jabbed me several times, and I took the jabs, wanting to increase his confidence. Then I saw him set himself for a hard jab . . . here it came. I brushed the jab aside — a lot like an uchi uke — leaned in, and put all I had into a left hook into his stomach. Then I didn’t even have to think . . . my right hand landed on his chin. I turned and walked to my corner. I had felt the impact in my right fist and I knew he was out. The referee counted him out, and the crowd went wild. My manager was glowing. I learned later that he was offered $10,000 for half my contract that night — in 1950 dollars. That’s like $100,000 today.

In a way Don Jackson had been my teacher. (And maybe I was his.) But not long after I fought him, I’d gotten drafted into the U.S. Army, and my fighting education had been interrupted — till now. The more I learned from doing kumite with Kancho Oyama, the more I became aware of how little I knew and how far he was beyond me. He told me once that he had never met anyone who trained as hard as he did, and I know that remained true to the end of his life.

The other myth I must dispel is a story reported in Shihan Cameron Quinn’s book that after watching Kancho break one brick, I asked him, “If I break two, will you give me 2nd dan?” and then proceeded to break two. First of all, in the more than 30 years of our friendship, I never asked Kancho for any rank or promotion. I would have died first. I believe such things cannot be asked for, and I am embarrassed by the behavior of some foreign branch chiefs who have demanded higher dan from Sosai Oyama or Kancho Matsui, or have complained about not getting the promotions they thought they deserved. It is not for them to judge what they deserve. They should keep their mouths shut and train.

Second of all, a real brick (that has not been secretly tampered with) is extremely hard to break, much harder than a cement brick. Only a god like Mas Oyama could break two. On his first trip to America he had fought and defeated challengers, mostly wrestlers, but this time it was with his miraculous feats of tameshiwari that Kancho wanted to impress the fantastic power of karate on the American public. I made arrangements with a friend for him to do a demonstration on television, for Channel 7, the New York City station of the ABC network. The week before the demonstration was scheduled to take place, Kancho broke a few bricks in our dojo to warm up. Then he set up another brick and said, “You now. Please.”

Kancho had told me how to develop the shuto muscle by hitting a wooden two-by-four five hundred times. I had done that on my own, and he had noticed my progress. Now, in a few words, he let me know that the key to tameshiwari, like the key to survival in battle, is mental concentration, determination and confidence. “Just you, and brick,” he told me in his new English. “Just you . . . and brick.” I had never broken a brick before, but I concentrated, hit it, and it broke. Kancho growled with pride, “Ohh. My student! You very strong.”

The first part of his demonstration was to be filmed outdoors, in Central Park. Kancho insisted fiercely that I be at his side. We also brought along our student interpreter, Yoshi. There was a public bathroom in the park where Kancho changed into his dogi. When we came out, I carried his clothes with me. In a grassy clearing Kancho stretched and threw punches while the TV people set up their equipment. A small audience was gathering, curious people who had been strolling in the park and were attracted by the ABC camera crew and their car. The assistant director asked when they could start filming. Kancho said, “Any time!”

He began by performing several kata, first basic pin-ans and then (if I remember correctly) Seienchin and Kanku-Dai, impressing the watchers with his serenity, majestic power and whipping speed. Then he looked at a nearby tree, which had a trunk about two feet in diameter. Yoshi and I knew what he wanted. We tied a towel around the tree trunk, at about Kancho’s shoulder height, to make a makiwara. And Kancho started to punch the tree. Whet . . . whet . . . whet . . . His low, growling kiais could have come from the bowels of a tiger. As Kancho’s power intensified, we heard a rhythmic rustling from above. The cameramen and the bystanders looked up. The leaves and branches of the tree were shaking with each punch! The looks on the faces of the ABC camera crew told the story. This was from another world, this kind of power.

Finally, Kancho searched around and selected two rocks. As he carefully laid one against the other, and then seemed to study them, the crowd fell silent. All chattering stopped. Kancho touched the upper rock with his shuto, and then with one sudden blow, shattered them both. There was total silence, and then wild applause broke out. Kancho was rather shy at this, but he bowed. The TV crew were overjoyed and very, very impressed.

An interview was still to be taped in the studio. We went back to the public bathroom so that Kancho could change back into his street clothes. From being outside barefoot, naturally his feet had gotten dirty. Inside the public bathroom there was running water, nothing else. I had thought of this, and had brought half a roll of paper towels. I laid some on the floor so that after Kancho washed his feet, he could step on the clean paper towels and then put on his socks and shoes. I have never seen such appreciation from anyone for such a simple thoughtful act.

I had slaved side by side with Omar in the Russian mine. Now I trained side by side with Kancho. For the second time in my life, working and sweating together forged a friendship stronger than the ordinary. But nothing welds a permanent bond between two people like the fire of shared danger.

The street was my element, and at times, my battlefield. That was something else Kancho and I shared. Both of us had been raised in good families, but then thrown out into life in our teens, forced to learn to survive and thrive unprotected. Can you imagine what it’s like to rely only on yourself, your own two fists and wits, not on your family, or your company, or the police? If so, you can imagine the luxury it was for Kancho and me to be able to rely on each other.

When we came back from training that hot early fall night to the glitter of broken glass and the screams of my customers, there was no one on earth I would rather have had by my side. I saw Kancho size up the seven punks as swiftly and expertly as I did, and as we decoyed them away from the coffeehouse, we fell into position like two knights riding into battle. He moved out in front, his modest size lulling them into carelessness, his Asian face inflaming their ignorant prejudice. I watched his back.

Whut! Whut! Whut! The leader’s heavy chain whirled like a deadly saw blade, circling closer and closer to Kancho’s head. Feet planted firmly on the asphalt, Kancho swayed and ducked in rhythm with the chain. Then suddenly he leapt right into its arc. Too fast to see, his right hand shot up and snatched the chain out of the air. He yanked it towards him and impaled the leader’s solar plexus on his left fist. “UUUHHHHH!!” The air exploded out of the greasy punk, and he sprawled gagging on the street. I looked at Kancho. His black eyes were shining with the fierce joy of battle.

For a split second the others hesitated, shocked. Then two of them grabbed my arms and a third tried to punch me in the stomach and groin, while the one with the fat gut swung his thick wooden two-by-four at Kancho like a giant baseball bat. Grabbing onto the two men holding me, I drove both feet into the face of the one trying to punch me, then wrenched free and, torquing left and right, smashed an uraken into the face of one and an elbow into the other’s rib cage. Moves coiled to steel by thousands of repetitions in the dojo. I felt bone and cartilage crunch and heard snarls of pain and rage. Kancho, meanwhile, was allowing the punk waving the two-by-four to back him towards the iron fence. For a moment he was still, and with a blood-curdling yell the fat creep swung the two-by-four down like an axe — but Kancho was no longer there. One end of the wooden beam lodged in the spikes of the fence, and with a kiai as if from the bowels of the earth, Kancho splintered it with his shuto. Then he thrust a terrifying mae-geri into the fat one’s soft underbelly.

At that instant I heard a whisper of leather. I spun around. A tall, sallow guy with bad skin and a raccoon’s tail dangling from his belt had drawn a bone-handled hunting knife and in one motion was throwing it straight at Kancho. All this happened at once, faster than it takes to tell it. Without time to think I brought my shuto down on the knife-throwing arm as if I was breaking a brick. I felt bone snap, but the knife was already flying through the air, deflected a fraction of an inch just as it left his fingertips. “Kancho!” I yelled. He reacted instantly, and the knife whizzed by him. He joked later that it was close enough to give him a shave, except that being Japanese he didn’t need one.

The leader still lay on the ground. The one Kancho had kicked was trying to crawl away. The other five staggered, stumbled and ran, clutching their injuries. There was a garbage can by the curb. Looking at Kancho, I picked up the gang’s leader by his waist, dragged him over and stuffed him headfirst into the garbage can. Suddenly I heard police sirens screaming closer. Time to fade away.

Kancho looked at me and grinned. “We go eat, okay?” And that’s what we did.

As that fall wore on, the weather began to get colder, yet I noticed that Kancho kept wearing the same summer clothes. I had escaped from Russia without warm clothes. I couldn’t feel right if my friend didn’t have warm clothes to protect him from the New York winter. Across from my coffeehouse was an established Italian tailor whom I knew well. One morning I asked him, “Can you outfit my friend?” He said, “Come in with him later, after three o’clock.” So that day we worked out early. By two o’clock we were sitting in our local Chinese restaurant, having bean cake soup and double portions of steamed Chinese vegetables. After that I took Kancho to the Italian tailor.

We found him a suit that fitted him like a glove, a handsome warm wool overcoat, and a raincoat. At a shoe store on the same block, I bought him one pair of black and one pair of brown shoes. Later we picked up T-shirts, shorts and socks. Then I felt better. After all that Kancho had given me, I didn’t need any thanks from him. I knew from his face what he felt. “Me never no forget,” he told me. And he never did.

As the Christmas and New Year holidays approached, Kancho started talking about going home. From time to time he phoned his family and his dojo. He insisted that the next time his dojo held a Kyokushinkai tournament in Tokyo, I must come and be there with him. I started feeling sad, and so did he as we sensed the approach of our parting. But our friendship was to last for the rest of his life — and beyond. in fact, with time it would grow stronger.

Before Kancho left New York, he wanted to give one climactic public performance to show what Kyokushin was all about. I knew what Madison Square Garden, the mecca of the fight game, meant to him, so I made some phone calls. From my fighting days I knew people associated with the Garden. Sure enough, they booked Kancho for a Saturday afternoon. We had two weeks to spread the word and publicize Kancho’s appearance in the Garden. An acquaintance of mine called a Mr. Friedman, who had been a colonel in the Armed Forces in Korea and supposedly knew something about karate. Mr. Friedman promised that he and some friends of his would mount a dynamic professional publicity campaign. It sounded good to us.

But as it turned out, Mr. Friedman and his friends didn’t do any publicity — or if they did, they did it very poorly. On the day of Kancho’s demonstration, the Garden was only half full. But Kancho put on a breathtaking show. He broke rocks, bricks, and two-by-fours like the one he had been attacked with. He fought five karateka from a dojo in New Jersey whom he had challenged. And as it turned out, Kancho reached a much larger audience than the Garden could hold at its fullest: the New York Times blazoned a headline across its sports page, “TOUGHEST MAN IN THE WORLD.”

In Kancho’s dressing room after the show I saw an expensive hat that belonged to Mr. Friedman. I was so angry at his broken promises that I took the hat. After the show we had a celebration at my “El Gitano” coffeehouse — it had a nice new plate-glass window now — and there I showed the hat to Kancho. He looked at it, looked at me with a michievous twinkle — and spat into the hat! Without missing a beat I spat in it too. Then we instructed the waitress to take it back to Mr. Friedman, and we watched like two kids, just waiting for him to put it on his head.

Shortly before Kancho left for Tokyo, he met an eminent Japanese journalist from the United Nations, Mr. Sho Onedera. Mr. Onedera was completely bilingual, as fluent in English as in Japanese. And so I gave him the manuscript I had written about my experiences. He read it, this book that you are about to read, and he told Kancho my story. Mas Oyama looked at me and said, “Ahh. Now I understand you.”

I only wish that Mas Oyama were here, because now at last he could read it for himself.

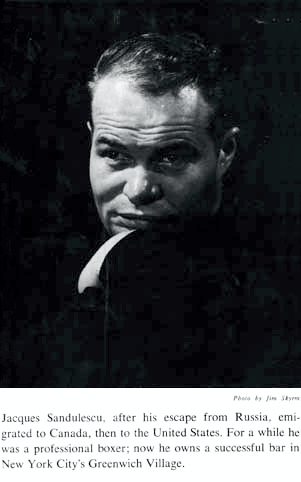

About the Author

About the Author

Jacques Sandulescu (1928–2010) was born in Romania and was arrested by soldiers of the occupying Soviet Red Army in January 1945, at age sixteen, because he looked big and strong enough to work. After his escape from Russia, he made his way to the New World, where he was a pro heavyweight fighter, interpreter in the US Army and the UN, jazz bar owner, actor (you saw him say “Is that your purse?” in “Trading Places,” “Liberty!” in “Moscow on the Hudson,” and “What the hell is ANSKY?” in a memorable New York Yankees commercial), and author. More than 50 years after his escape, Jacques returned to the Donbas region where he’d been a prisoner, a story told in the epilogue of his book, Donbas: The True Story of an Escape from the Soviet Union.