When the average American hears “tai chi,” the image that springs to mind is of little elderly people practicing gently in the park. That doesn’t describe Master Fu at all. Fu Xueli, or Jack as he likes to be called here, is a big man for a mainland Chinese. He has the kind of stout body that’s well-suited for wrestling or mixed martial arts. And he’s young. His disarming baby-face smile accentuates his youthfulness. That smile has served him well navigating the political hornet’s nest of communist China and its continually changing attitude towards the martial arts. Before immigrating to the United States, Master Fu was a government man, working to revitalize one of China’s most prominent metropolitan martial arts organizations. He is a prime example of a “next-gen” master from the People’s Republic of China.

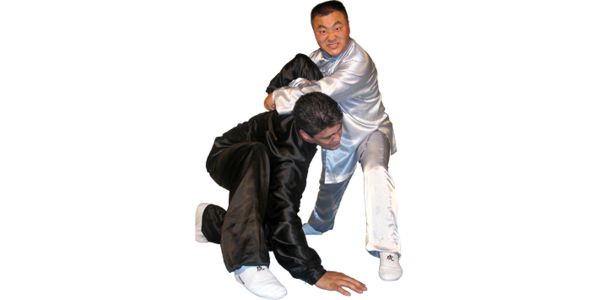

Today, Master Fu’s passion is tai chi sparring. A master of pushing hands, or tuisao, Jack is always eager to touch other fighters. “If I hear who is good, I also want to try him,” Jack says in earnest. “I don’t want to see ‘you win, I win.’ Sometimes I can win. Sometimes I lose. It’s okay because I’m young. But I just want to try things. I just touch, I can learn.” Fu’s non-confrontational attitude towards tai chi was the core of his strategic diplomacy. He succeeded as a martial community leader by adopting tai chi tactics on the job. More importantly, this philosophy allowed Master Fu to amass an astonishing array of combat skills shared with him by masters from all across China.

A Son of Sichuan

Though Jack’s grandfather hailed from Hubei Province, Jack’s father came to Sichuan to teach at a Chengdu middle school, eventually becoming headmaster. Thus, Jack is a born-and-bred Sichuan native. Though he says he started practicing kung fu at age nine, he is being humble about his earliest beginnings. His father, Fu Liqing, was a traditional kung fu master who took Jack along for his morning practice. Every day Jack watched his father exchange techniques with other masters. Every day his dad forcibly stretched Jack’s legs into splits and showed him basic combat skills. This early exposure earned Jack a place in an amateur Jinniu District martial arts school. Despite his father’s personal tutelage, Jack cites his entry into that school as the beginning of his formal martial training. “If from beginning, (I) study kung fu (from) very young, you know, three years old.” says Jack smiling innocently. “My father, he (go to) morning practice, always take me out (from) very young. I say ‘nine years beginning study’ because I go to xiaoer xuexiao (youth school). I don’t know what’s better from me.”

Like most of his generation, Jack trained and competed in modern wushu forms at that school. In his late teens, he was accepted to Chengdu’s prestigious sports college. There, Jack studied martial arts and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Many traditional masters like Jack’s father were proficient in Chinese herbs. Fu Liqing passed his herb knowledge down to both of his two sons. Jack’s younger brother parlayed that knowledge in a career as a doctor. Jack graduated with a four-year degree from the sports college in martial arts and earned a TCM license as well.

It was in college that Jack began to spar regularly. During that time, the government began promoting a new martial sport. Sanshou (literally “loose hand”) was a newly-regulated sparring game sweeping the nation. Two major innovations set sanshou apart from other forms of kick boxing. Firstly, it is fought on a traditional, elevated platform called a leitai with no ropes or turnbuckles. A fighter scores by throwing the opponent off the leitai. This arena is completely opposite to that of cage matches, so attack and defense strategies are different. A fighter can’t trap an opponent in the corner. The other innovation was awarding points for takedowns. With takedowns in the arsenal and only light padding on the leitai, hard throws can be devastating. Throwing the opponent off the leitai makes for a thrilling spectator sport. Sanshou has become an important facet of modern wushu and continues to grow internationally.

The First Sanshou Study Camp

Jack graduated from college in 1994 and immediately accepted a position as the new leader of the Chengdu Wushu Association. According to Jack, he got the job because his kung fu was “good” and his timing was right. “They need a new one to control this department,” admits Jack, “so I do that job.” For five years, the Chengdu Wushu Association had been defunct. Jack had a lot of work ahead of him if he were to succeed. Fortunately, the government stepped in to help.

In communist China, the government controls every sport from soccer to ping pong, so the fledgling sport of sanshou fell under government jurisdiction too. In order to develop and promote sanshou, the Beijing Wushu Association held a special sanshou camp. The first one was held when Jack took office, so he was invited. Sixty experts gathered in a remote camp to work together to expand sanshou’s viability. Fifty of them were from the private sector. At that time, Wuhan and Dalian were the leading authorities on sanshou, so both sent emissaries. Also among that fifty were top sanshou coaches, national champions and headmasters from various schools from across China. The other ten were people from government positions like Jack.

The experience opened Jack’s eyes. It also gave him a chance to test his skills amongst China’s finest. Fresh out of college and one of the youngest participants, Jack was like a sponge absorbing everything he could. “Every famous master teach me a lot,” remembers Jack. “Eat and fight. Every day (was) like living in a wuxia (literally ‘martial knight’ which refers to a popular genre of martial arts fiction in books and movies). Class was just a short time, morning to afternoon, then finish. Then everyone drink. That place was a chicken farm outside in the country – nothing around us. Everyone finish and drink. They come (from) different schools. Some people don’t like other people. Everyone wants to challenge. We always go watch. ‘Ok, go! Go!’ Some like to break stones, break bricks, everything (laughs). Because that time, every school (was) just beginning sanshou. (The) government helped the schools to promote faster. I meet a lot of people, many totally different – very early touched them. That helped me a lot.”

A Kung Fu Government Man

Inspired by the experience, Jack returned to his new post at the Chengdu Wushu Association. Chengdu is the fifth most populated city in China, close behind Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai and Tianjin. With so many people, Chengdu is home to a lot of martial artists. Jack estimates that there are more than a hundred thousand practitioners in Chengdu. Despite this enormous community, the Chengdu Wushu Association was virtually non-existent when he took the helm. Jack pleaded for government assistance and after much lobbying received $1000 RMB in financial aid to revitalize the organization. With that small start-up fund, he rallied the locals to donate more.

Jack implemented a grass-roots campaign to expand the association. He established several monthly competitions, arranging special competitions for young children, young athletes and senior citizens. By increasing the number of competitions, more people had a chance to win. This attracted an enthusiastic crowd of competitors, spectators and volunteers. Jack also created government-endorsed honorable titles and awarded them to deserving members. Initially, many Chengdu masters were wary of this young government upstart. But Fu’s father had instilled his son with a traditional upbringing, so Jack knew how to properly show respect. “I try my best (to) give balance,” reflects Jack. “Very difficult, but ok. So everyone happy, join us. Very fast.” Jack treated everyone so humbly and politely that he turned their opinions about the government around. “In China, everyone trust the government,” states Fu, smiling like a senator. “If you have a license, they trust you. I make a license – give them. I find every practicing kung fu guy. They want government help. They want government to control them (so) they go outside (and) teach kung fu. So everyone want to join.” By the time Jack left his post, the Chengdu Wushu Association’s budget had blossomed to more than $1,000,000 RMB annually, with a minimum of $20,000 RMB in the bank at all times and annual membership fees totaling over $100,000 RMB. Chengdu martial arts rose to be ranked as the third best in China.

Pushing his Master’s Son

As a practitioner, Jack discovered a huge perk in his post – access to the masters. As his career took off, so did his martial knowledge. Jack was constantly meeting new masters and seeing new methods. “I meet a lot of very famous teachers,” says Fu, “because somebody introduced somebody. Everyone want me (to) know them and help them. And they teach me a little bit. I always watch. I don’t want begin my school. I never show anything to other people. Then I meet a lot (of) very famous headmasters and they know me. They trust me. They tell me a lot. Everyone tell me something.”

From these exchanges, Jack developed a keen interest in tai chi tuisao. “University tai chi just teach move,” observes Jack. “Very beautiful – speed control very good – but sometime teacher teaching is wrong. (They) don’t let power from foot go to waist. It really can’t get out.” Now Jack was meeting new masters, ones not bound by academia. Jack grew to appreciate the wisdom of the way of soft combat. “I feel other kung fu (is) just fight, but tai chi really has very deep internal. I (am) very interested in that. Power from internal is power that can move other people very easy. In my office, everyone come, I welcome push them. Dinner can wait. Push first. Hard qigong is ok. Kung fu is ok. But that touch is totally different.”

After his first year with the Chengdu Wushu Association, Jack had an encounter that would change his life. “My kung fu in that time, it’s ok. I (was) almost 90 kg. (When) I go to Chengdu Wushu Association, I begin at 70 kg. (After) one year, every day eat, drink, pork, everything, go watch this, watch that – very good!” Jack laughs and pats his belly. “Before this, I training very hard. That year was lazy. Then I meet my teacher’s son. He just half my size. I test his tuishou. I try him. I cannot believe I cannot move him. I push him, but I fat. I cannot move him. Big surprise! I study kung fu long time, start at nine years old, then university, then always fighting, job, fighting. I fight a lot – everyday fight. I trained fighting every day. He was like a fish, very slippery. I cannot control him. He was very strong too, small guy and powerful. I was a little scared. That power was totally different. I feel that’s power across your body. I always feeling he (in) control. He don’t let me die, but always like I’m walking on the blade. I never felt this before and I met many, many famous teachers. Nobody had that.”

Jack followed that tuishou master to his father, Yang Tai Chi master Lin Mogen. Lin was a slim man, but extremely powerful. Again, Jack was astonished that his weight and height advantage were inconsequential. Jack began practicing tuishou with Lin’s group, but progress was slow. Being a traditional master, Lin was very guarded about his secrets. What’s more, there was some awkwardness about their status. Jack’s position with the government meant he was higher ranked than Grandmaster Lin. He considered becoming Lin’s disciple, but he would have to do it secretly. Also, the baisi (a monetary gift given to the master from the new disciple was very expensive. It was as much as Jack’s annual salary. “Made me think long time,” sighs Jack.

Grandmaster Lin’s 108 Techniques

“Nobody can say he study all of tai chi,” states Jack. “My teacher always say he just study tai chi a little bit. Sifu always tell me his studies (were) very difficult from his sifu because at that time, sifu very closed. Now he teach me. It’s open a lot. Then I tell my students. I know why many traditional teachers don’t want to teach the students a lot. First, they’re old. Second, they’re too closed. I’m young so I open a lot. Of course, I’m from China, so I have a little closed too, a little traditional too, but much better.

“My teacher had one-hundred and eight gongfa (literally ‘work methods’ – it’s the same gong as in gongfu or kung fu and it refers to special fundamental techniques). That’s all his secrets. You study it very fast. If you tell everybody, (they’re) very fast (too), so sifu keep something for us. You don’t need all to practice. Just practice ten, eleven, twelve, then you can fight very fast. I’m very luck with my teacher, because my teacher had something very special inside. I go inside. I got it. Now I become American. My teacher agreed me (to) teach. He hopes I can get more disciples (to) teach.”

“My teacher always tell me, first you can study from your students. Because they always push you, you improve yourself. He improves, you improve more. Second, if you touch a kung fu guy very close (to your level), you study more. If you touch very high guy, you study a lot. Now I really want to find one very famous and very good teacher. I want to follow him and study.”

When Push Comes to Shove

In America, there’s an ongoing debate over push hands. Some practitioners believe tai chi should always be soft. When it gets hard, push hands starts looking more like sumo wrestling. Critics discount such bouts as not being ‘true’ tai chi because fighting like that loses the essence of internal style. Jack sees it diplomatically. “A lot of people play tai chi. I believe eighty percent just know how to play. (The) other twenty percent know push hands. But this twenty percent, maybe fifteen percent of (the) people just know how to move. Really, just five percent know how to really get power out – how to use internal power to move you.”

“I’m originally Yang. I never see my kung fu as very good because a high tai chi kung fu guy, that’s a lot. I like to collect everything. I don’t care – Yang style, Chen style, Wu style – if it works, I get it. Next time (when) fighting, I find this works, I get it. I build my system to include every style inside. Push hands don’t care what style. You go (to) competition, you really can use (it) or not.

“If from Yang style, my sifu always say to me ‘Just relax. Always the gentleman.’ If you want ‘gentleman,’ I let you do ‘gentleman.’ We do tai chi feeling. I let you fight me very comfortable. If you want to do very fast, ok, I can do same. Sometimes you need to try feeling internal power, feeling other people, slowly, gentlemanly. That’s one tai chi way. Another way, if you go (to a) tournament to become a champion, you cannot always (do) that. Because if you always (do) that, you will lose. Sometimes, use hard more because your kung fu not enough. If you’re the same level, better you’re a little bit hard. Better don’t (be) too gentle. Then you lose.

“I can use one finger and control you. I touch you. I feel you. I can control you. I practice this because that’s really tai chi. Gentleman. We can control. I like that. I like gentleman more. Fight – ok, you come, I can fight you. But fight always hard and sometimes no too good because easy (to make) mad. I don’t want (to make) anyone mad.

“Tai chi fighting (is) totally different. For tai chi push hands, I tell them you need to feel soft, gentleman, internal, that’s really good too. You can get a lot of students. But another way, students want to be good fighters. They want to be champion. Sometimes you need peng (one of the eight essential energies of tai chi) more. I never see power to power. You just follow him, change, or go other way. You cannot be too gentle. Yang style always do peng. Chenjiagou (Chen family village) always, a lot of people want more fighting. Sometimes I like that, because it’s good, but sometimes, other people say ‘that’s no tai chi, that’s like fight.’ So I always agree (laughs).”

Pushing For Tomorrow

Here in America, most push hands competitions are confined to a ring that is little more than a taped-off section of mat. In Chen village, push hands tournaments are often fought atop a leitai, like sanshou. In the rest of mainland China, the game continues to evolve in other ways. New variations of push hands competitions include moving push hands atop a low banister and stationary push hands atop meihua zhang (plum flower posts – similar to telephone poles). There’s even a version where competitors don’t touch. Instead, they both hold on to a pole and engage in what could be best described as the opposite of tug-of-war. Jack got funding from the wushu association to develop another new twist. Working with Grandmaster Lin and his martial brother Wu Xinliang, they created a very challenging game. “We designed two gates,” explains Jack. “We make the gates very big. If you really have tai chi kung fu, you can control my power (to) go which direction. If you push them through the gate twice, (there’s) no need for another fight.”

With our current fascination with MMA and cage fights, tai chi is far from the spotlight. The idea of tai chi in a cage match seems absurd. But according to Master Jack Fu, the value of tai chi and kung fu lies within its diversity. It’s not about dominating the octagon nor is it about winning in push hands. It’s about finding yourself. “Of course, fighting is different. If you fight, I have a lot of sanshou (and) qigong, I can fight to you. But I don’t want to, because push hands is very interesting, very gentle things, very internal things. You can give me power, very strong, ok, but that’s totally different because (in) kung fu, nobody is Number One. This part, you may be Number One. Other people, fighting, may be Number One. Other people, maybe the kick, Number One. Everyone cannot practice every part. You need to practice something special for you.”

Written by Gene Ching for KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM

© COPYRIGHT KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

All other uses contact us at gene@kungfumagazine.com