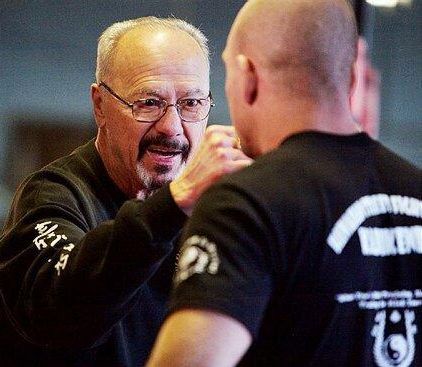

. . . guys like Great Grandmaster Charles Gaylord, brought mixed martial arts from Hawaii — where the art form was created — to the mainland and introduced it to the rest of the world.

East Bay Times ~ With televised cage matches and scores of professional fight leagues, mixed martial arts stands as one of the most popular and exciting sports to follow these days.

But what we see now probably wouldn’t have been possible if it weren’t for guys like Great Grandmaster Charles Gaylord, who brought mixed martial arts from Hawaii — where the art form was created — to the mainland and introduced it to the rest of the world.

Back in his day, though, when it was just about street fighting, there were no cameras, no corporate sponsorships, no cages. Just survival skills.

“In the street, there are no rules,” he said. “But a poke in the eye, a chop in the throat, putting a guy out at one vital area, you can’t do that (in the professional mixed martial arts world) because there are rules.”

More than 40 years after Gaylord first arrived in the Bay Area and began in San Leandro teaching kajukenbo, the world’s first mixed martial art, he and the art he helped cultivate are finally getting their due.

Gaylord will be featured in a new show, “Warrior Quest,” scheduled to air nationally on the Discovery Channel later this month.

Make no mistake, he is definitely proud to be part of something that will give what he has dedicated his entire life to even more validation.

But the grandmaster, whose relatively small stature belies his physical and mental strength, knows this exposure is much deeper than that.

“It took 50 years because of the jealousy that’s in the martial arts world,” he said. “But, for once, we can expose this — that this is who we are.”

Kajukenbo is actually a combination of words, taken from the different martial arts styles it comprises: karate, judo, jujitsu, kenpo and kung fu.

Contrary to what it translates into, “street fighting,” the martial art has never been focused on violence. Like most martial arts, kajukenbo was started for defense purposes.

A group of five men, known as the “Black Belt Society,” decided to bring together their different martial arts styles so that they could defend themselves from the often-rowdy soldiers left in Hawaii after World War II.

Of the masters who then brought kajukenbo from Hawaii, Gaylord is the only one still alive on the mainland.

When he started his school in San Leandro in 1964, Gaylord said, he knew things were different. Students would not have to fight against soldiers.

But they might have to defend themselves from some rowdy patron at a bar or a club.

And during the 1960s and 1970s, when martial arts were very popular, kajukenbo students would be facing off against equal, if not better, opponents.

So Gaylord created his own method, aptly called “Gaylord’s method,” which stayed true to the art of kajukenbo but became more advanced and functional.

“I wanted kajukenbo to be better, quicker, faster,” said the 71-year-old, who now lives in Fremont. “And the older I got, I wanted it to be much more simple.

“I wanted to just touch you and knock you out,” he added. “I didn’t want to fight for five hours. That was more fun, in fact, after a while.”

As brutal as that sounds, kajukenbo today is taught only for self-defense in schools throughout the world. There also is a governing body that oversees the martial art.

Under Gaylord’s direction alone, about 30 schools have been created throughout the Bay Area and in New Mexico, Idaho, Texas and Portugal.

Some of the more notable schools in the Bay Area include Esteller’s Martial Arts in San Leandro, U.S. Karate and Boxing in Hayward, Bono’s Kajukenbo in San Jose, Delta Kajukenbo in Tracy and Oakdale Kajukenbo in Oakdale.

But Gaylord’s greatest contribution, said Ron Esteller, one of Gaylord’s students who runs the school in San Leandro, has been his insistence on keeping kajukenbo a unit — a principle that stems from its origins in Hawaii.

Esteller said that if a kajukenbo fighter serendipitously meets another on the street, they immediately become friends because Gaylord cultivated that brotherhood — and that same principle was passed on to Gaylord from the martial art’s founders.

“We all stay together because we’re all family,” Esteller said. “It’s that ‘ohana’ he created.”

The Discovery Channel’s launch of a new show featuring kajukenbo — in which Gaylord teaches the art form to a professional mixed martial arts fighter — brings Gaylord and all kajukenbo fighters a great sense of pride, he said.

Ironically, he added, the show has also done something else: It has united the kajukenbo world once again.

And just like when he started teaching in San Leandro some 40 years ago, Gaylord said he plans on keeping it that way.

“I’m not letting anybody destroy that family,” he said. “And if that happens, it’s going to be the strongest martial art in the world.”

By MARTIN RICARD | Bay Area News Group