The afternoon sun still drifted through opaque windows at the end of the gymnasium and offered a smidgen of hazy twilight to my corner of the stands. Contestants and judges buzzed about the floor in constant activity and watchers came and went through the double doors at the other end of the room.

It was 1974. Tournament karate was young and exciting. Nowadays tournaments often feel like the proverbial hackneyed nag, tired from use and abuse, but, back then, they were fresh and still new, full of undiscovered challenge. No one knew where we were going, but it was a great time to get there.

I endured the hard wooden bench alongside a friend, reviewing the competition and possibly waiting to judge an event or something. Having studied Shotokan karate, (sort of) for a whole 10 years, I was confident of my comprehensive knowledge of karate. My friend, with the same years in Japanese Goju Ryu, seemed even better qualified. We passed the time in random conversation, artificially sophisticated in our martial opinions.

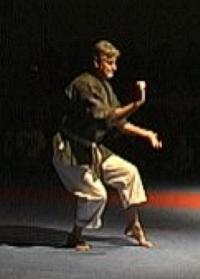

We idly chatted while one competitor followed another. Then, as I turned away for a second from the competition, I heard what sounded something like a corn threshing machine gearing up in the center ring. I looked back the sound in time to see a long, lanky, military-cut black belt stomping, snapping and shouting his way across the floor through Seisan, with enough power to light up a small town electric grid. I watched in amazement, wondering in disbelief if there was possibly something I had missed in karate 101.

“What’s that?” I asked my friend.

“It’s supposed to be Goju Ryu,” he answered, condescendingly, “but I’ve never seen Goju Ryu that looked anything like that before.” And he brushed it off as maybe some buffoon trying to compete.

In the ensuing years, I came to realize the significance of that statement – and how typical of the karate circle within which I moved. We all thought we knew so much and we knew so little. I get embarrassed at the memory.

What he said was painfully accurate. Even after 10 years in the art, he hadn’t ever seen Goju like that before and neither had I and neither had a lot of people in the karate world of the day. But it was real Goju, authentic and straight out of Okinawa, right where it all began.

I had become accustomed to Shotokan – adapted from karate by the JKA to win tournaments – and soft Japanese Goju with its hint of mysticism and its long haired teacher, or snappy Shito Ryu. But this was something different. This guy looked like he could actually hurt somebody.

Lee Gray topped off his kata with a confident bow, strode from the floor and opened more than a few eyes about what Goju karate is and isn’t. He set at least one mind grasping for explanations. There’s something about his stretched out legs and arms that combine with Goju principals to fire up a power not born of weight-trained muscles, but of proper application and decades haunting sweaty dojos.

I stumbled my way down the bleachers, ambled across the floor and offered the dude my hand. We recently reminisced about that long ago day over a Corona.

In those days most people thought of Goju (if they thought about it at all) in terms of Gogen Yamaguchi, the character popularized by the martial arts media of the era and the originator of “Japanese” Goju Ryu. Yamaguchi ginned up the proper sixties shoulder length hairstyle and bragged a catchy moniker, “The Cat”, so he made for good press. Those who knew karate in more depth might have thought of Chojun Miyagi, the legendary Okinawan founder of Goju, or perhaps Eiichi Miyazato, his student.

But, there weren’t actually a lot of people around then who knew karate in more depth, or any depth at all, for that matter, nor who knew that there is a significant difference between the Goju of Okinawa and its Japanese cousin. That hazy day in California, Lee Gray laid out the difference in plain, easy-to-understand terms – power. Some see Goju as soft and flowing. Goju from Okinawa is unflinchingly powerful. The name means “hard-soft” or “hard-gentle” and implies Yin and Yang, but while watching Okinawans and Texan marines demonstrate, the word “gentle” never really springs to mind. In Okinawa it’s the Goju fighters who kick holes in kerosene cans with their toes.

When Miyagi abandoned life in 1953 he left several students and contemporaries who had studied with him or with his teacher, Kanryo Higashionna. Seiko Higa, Meitoku Yagi, Seikichi Toguchi, and Eiichi Miyazato all carried on Miyagai’s song, but to their own beat. Miyazato’s dojo, the Jundokan, is probably the most renowned, but there are others equally as devoted to Miyagi tradition.

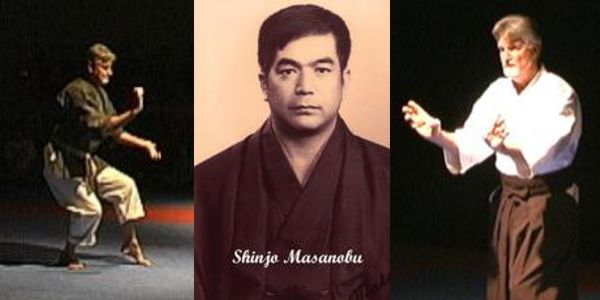

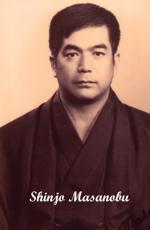

A quiet strongman named Masanobu Shinjo, pictured here in his youth, started one such organization, the Shobukan, in 1963. Shinjo first drew breath on Rota Island in Micronesia in 1938 and emigrated to Okinawa as a child. His father, a sumo wrestler, was one of the few Okinawans invited to wrestle for a Japanese stable. Shinjo, himself, even tried his hand at sumo as young boy. His overstuffed muscles reflected his father’s genes.

Shinjo began training in 1953, the year Miyagi died. He yearned to capture Miyagi’s unique style as closely to the Master’s way as possible and, as the years passed, made it a point to search out individual Miyagi students to learn their take on his katas and system. One old Miyagi disciple offered the thought that Shinjo’s movement looked more like Miyagi’s than anyone he had ever seen.

Students and scholars say that Miyagi, like Higashionna before him, didn’t teach all kata to all followers. Hence, one might have become proficient in Sanchin, which everyone learned, and one or two other kata, but not know the rest. Shinjo sought out as many students as he could for a better understanding of the entire deal. Because of the fact that Shinjo didn’t study directly from Miyagi or Miyazato, he passed on a style that is very slightly different from what might be considered “standard” Goju, although, human individuality being what it is, that term really has little practical meaning.

Lee Gray met up with a Marine recruiter in Amarillo Texas while Eisenhower was still president and shipped off to Okinawa. He soon found his way to the Shobukan, where he first had to prove his metal before anybody would pay much attention to him. As you probably guessed, he succeeded and spent the next 42 years punching and kicking and stomping through those kata, sometimes directly with Shinjo, sometimes with other students, sometimes on his own, pretty much the same as most of us.

Two tours of duty and action in Viet Nam nurtured within him an attitude that most of us dojo students never really understand – zanshin – the ever present awareness, the key to survival for medieval samurai and modern Marines. Nothing develops zanshin in a warrior more than wading through elephant grass, passionately aware that an enemy is out there intent on slicing your throat to the bone. It’s a consciousness soldiers in combat regularly acquire, regardless of the century in which they fight. Most of us, fortunately, never undergo such a deadly test.

Lee Gray did. After the Marines he became a prison guard, a job where zanshin becomes a way of life, and then a defense instructor for prisons and police departments. This practical application of kata and bunkai imbues Lee’s classes and seminars with a gritty edge. He teaches karate techniques backed up by real-life tales. This worked – that didn’t.

Lee also studied Okinawan kobudo and the Japanese sword and teaches those arts, along with Goju Ryu, in his dojo in Amarillo, occasionally venturing out to offer up a seminar on one aspect of that long history of martial arts or another. In his sixties now, his kata still sounds like a thresher in high gear, and he stomps even harder than ever. When you spar him, he’s so tall and lanky it’s like trying to dodge a helicopter blade. But, like Shingo and Miyagi, Lee has not lost his gentleness. The hard and the soft are embodied in his manner. His kata and his no-nonsense gaze exude power. His quiet demeanor reflects his gentle heart.

Lee’s life embodies another principal – an idea that says that karate does not make us what we are, but, on the contrary, we make karate what it is. We often see ourselves defined by our art, molded and nudged into our current embodiment by the techniques and philosophies of some bygone Oriental golden age. But, in truth, modern warriors define modern karate. We direct how it is taught and perceived. If we pass on diligence, power and tradition, karate will become diligent and powerful and tradition filled. If we sport red, white and blue uniforms with our name splashed across the back and broadcast our inflated rank to whomever will listen, karate will become that.

It is not the same art Okinawans practiced 300 years ago, or Chinese a thousand years before that. It can’t be, we’re different people and what karate will become in the future is up to us to decide.

Shinjo wrapped up his time on earth in 1993, a victim of leukemia. I had the opportunity to interview him at a Las Vegas event just before that sad day. The first thing that struck me was the strength he exuded, even in the middle of a terminal illness. He performed Suparempei at the event and demonstrated the magnificent end result of a lifetime of dedication to an art.

The second thing was his gentle, casual demeanor. He epitomized Okinawan karate attitude as much as karate power. I had long been accustomed to mainland Japanese instructors who often strut like Sergeants ordering Privates. Shinjo, the Okinawan, was as unassuming and relaxed as a worn out old chair and treated me, because of Lee Gray, like a long lost friend. He inquired if I spoke Japanese and, when I responded yes, if he spoke slowly, he started talking to me like I was a little kid. I chuckle, even now, at the pleasant memory.

He leaned sprawled back against the head board of his hotel bed with his uniform top hanging open and talked about how much he liked the United States and its people and how Okinawa and Japan had no corner on the mastery of karate. He gestured towards Lee as he pointed out that he didn’t know many little Okinawans who would stand a chance against a six-foot-four Marine with legs and arms like oak limbs and 35 years of karate under his shaggy belt.

Teachers who approach an art with dedication, perseverance and great commitment inspire great allegiance in disciples. Such was Shinjo. Many organization heads are so demanding and caught up in politics and profits that students quickly come and go, always looking for higher rank or better position. In the 35 years since I shook his hand that day at Dan Ivan’s tournament, I have never heard Lee Gray even suggest that he should follow someone else. I also never heard him talk about rank, and, in fact, after all those years, I didn’t know his rank until I interviewed him for this article.

We all know that the practice of karate can take us to new levels of understanding on both sides of the Force. It can reveal within us either great human spirit or ego driven pretense. People like Masanobu Shinjo and Lee Gray have defined their karate. They practice a different style than I, but, as you can tell, I admire them greatly. They have made karate what we have inherited and what we pass on. Their dedication and perseverance can be a motivation to us all. It behooves the rest of us to work as hard and live as softly as they.

By the way, if you want to know Lee’s rank, you’ll have to ask him yourself. Chances are you can find him in his dojo in Amarillo – practicing kata.