Problem: You may not be able to execute intricate martial arts techniques in a fight. Solution: Learn simple moves for defending yourself with a cane!

Martial arts instructors are very good at preserving their art and equally good at teaching basic self defense what they don’t focus on often enough is the bridge that connects training with the street. The structure of the bridge must take into account the physiological effects that high stress situation have on the mind-body connection.

Anatomy in a Crisis

Those physiological changes determine what works and what doesn’t in a fight, and like it or not, they indicate that there’s a big difference between training in a controlled environment and self defense in the real world. Moves that are easily performed in the dojo become difficult or impossible in a dark alley.

According to Warrior Mindset, by Michael Asken, fine-motor skills start to deteriorate when your heart rate reaches 115 beats per minute. At 145 bpm, your complex-motor skills begin to deterate. Above 175 bpm, you experience irrational urges to fight, flee or freeze. The optimal heart rate for survival and combined performance is 115 to 145bpm–assuming you’re well-trained and physically conditioned.

You can’t stop these bodily changes from occurring; the best you can do is limit their effects by focusing portions of your training on what really happens on the street. That will enable you to find ways to take advantage of the physiological effects. In a nutshell: When your heart is pounding and the adrenaline is pumping, techniques that revolve around gross-motor skills will be more effective.

Martial Arts In Said Crisis

Deadly force encounters, by Dr. Alexix Artwohl and Loren W. Christensen, provides valuable insight into what happens in combat. Among the effects you can expect are visual narrowing, accelerated breathing and reduced cognition.

Once in survival mode, your body move blood to larger muscle groups, which precipitates a drop in fine-motor skills and dexterity. As a result, simple acts like using a key to open a door or sending a text message on a cell phone become extremely difficult, if not impossible. Needless to say, complex martial arts moves suffer the same fate.

The good news; Knowledge that these changes are inevitable can help you deal with them in training-before you experience them on the street. Specifically, the knowledge should motivate you to formulate a self-defense plan that relies on techniques that don’t require fine motor skills. Even better, use a weapon.

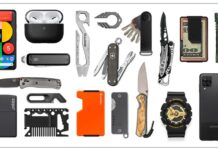

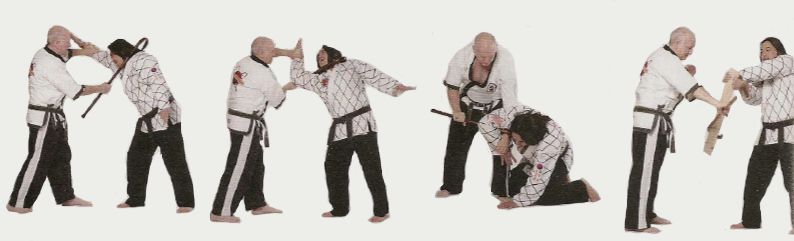

Mark Shuey Sr. demonstrates four basic self-defense moves from his American Cane System: blocking, poking, swinging and pushing.

CANE TO THE RESCUE

Unfortunately, that loss of fine-motor skills also degrades the effectiveness of most weapons techniques, which depend on precise sequences of movements and a level of accuracy that’s impractical in many self-defense situations. The solution entails recognizing one simple fact: If you’re like most mar-tial artists, in your arsenal are probably only eight to 12 techniques you’ve practiced so much that you can do them with a high degree of skill under duress. Because a weapon is essentially an extension of your body, this also applies to self-defense with blades, bludgeons and so on. Ignore that, and you’ll lose the fight before it even begins.

Although it’s often overlooked in the dojo, the cane is perhaps the premier self-defense weapon. Why? It doesn’t require fine-motor skills or thousands of repetitions to become proficient. Its basic techniques revolve around gross-motor movements such as blocking, poking, swinging and pushing. Further-more, the design of the cane facilitates its use in more advanced maneuvers, which can be pulled off if sufficient practice has been undertaken. For ex-ample, the crook of the cane—assuming it’s properly designed—enables you to hook, crank, immobilize or redirect, depending on the situation.

Scenario: You’re walking through the park when you’re confronted by a man who demands your wallet. Remember that he’s feeling the same physiological changes you are—visual narrowing, selective attention, reduced cognition and so on—but he doesn’t know it. You stop, raise your left hand as if you’re surrendering and start talking. You ask what he wants and beg him not to hurt you. Meanwhile, your right hand remains on the cane.

As soon as he starts to answer, you flip your cane into his groin. When he bends down, you grab the cane with both hands, step forward and effect a brachial stun by slamming it into the region where his neck joins his shoulder. If that doesn’t knock him down, you plant the crook behind his neck and pull him to the ground.

FOUNDER ON A MISSION

Mark Shuey Sr., founder of Cane Masters, is the best-known proponent of using the walking stick for combat. The art he created, American Cane System, is pure self-defense.

The cane is a standout tool for this, he says, because it’s legal to carry any-where. Reality check: You may be an ace with a tai chi sword, but you’ll never have one strapped to your belt while walking around the mall. But you can carry a cane there, whether you’re us-ing it as a walking aid or not.

Although ACS incorporates more intricate maneuvers at the intermediate and advanced levels, its core is designed around the mind-body connection—and all those adrenaline-induced limitations mentioned earlier. Its basic techniques are easily applied while under stress, and many function as well when you’re sitting as when you’re standing.

Shuey’s newest program is called Cane-Fu. He designed it to meet the needs of people 50 and older, as well as the disabled. “The Cane-Fu system contains the most efficient and effective exercises and self-defense techniques from the American Cane System,” he says. “The [skill sets] are easy to learn and will help instill a sense of confidence, as well as a higher level of health, to those who are willing to delrote the time to practice them on a regular basis.”

Because Cane-Fu techniques are easy to learn, they’re also easy to retain. They form a solid foundation on which a dedicated practitioner can build a more formidable system, Shuey says. “With a little imagination, you can create your own techniques that will feel natural and reflexive.”

Despite his claims that Cane-Fu is intended for seniors, its open-ended structure means the system will satisfy any martial artist who wants to devote his training time to the weapon. I can say that with assuredness because I’ve been involved with the cane for more than 12 years, and I’ve yet to tire of it.

PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE

The only way to mitigate the loss of ability you experience in a fight-or-flight self-defense situation is through practice. if you invest the time-and have the right instructor-you can reduce the effects to a more manageable level. The key is to train consistently with a high number of repetitions.

Pro fighters, as well as specialized law-enforcement officers and members of elite military units, train to develop their ability to operate at an elevated state of arousal for significant amounts of time-all while remaining effective. The “secret” is quality training, and lots of it. You can’t work out four hours a month and expect to immunize yourself against the effects of adrenaline.

Kevin Dillon, a longtime martial artist and police combatives instructor, said it best: “Your body will dictate your physiological changes during a violent encounter: your training will dictate your response.”

Amaury Murgado was introduced to the cane during a Mark Shuey seminar in 1999. A columnist for Police magazine and a police combatives instructor, Murgado is the special-operations lieutenant for the Osceola County Sheriff’s Office in Kissimmee, Florida.