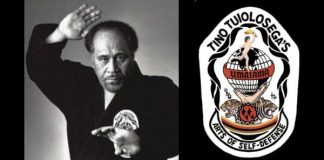

Secretly, in the dark of night, the ancient warriors practiced the deadly moves involved in the art of self defense called Lua (Kapu Kuialua). It was a discipline that required balancing the practitioner’s spiritual and physical aspects in order to achieve victory in battle as well as harmony in everyday living.

Secretly, in the dark of night, the ancient warriors practiced the deadly moves involved in the art of self defense called Lua (Kapu Kuialua). It was a discipline that required balancing the practitioner’s spiritual and physical aspects in order to achieve victory in battle as well as harmony in everyday living.

Two of several definitions for “Lua” appropriately portray the discipline. The word “Lua” can mean “pit,” as “to pit in battle,” or it can mean “two,” expressing the duality involved in this Hawaiian martial art. A similar duality in Hawaiian belief is embodied in Ku, considered the positive male god, and Hina, the negative female. Hawaiians believed by learning to balance life’s negative and positive forces-the physical and spiritual, emotional and intellectual-a lua master, or ‘olohe lua, could turn an opponent’s energy into a force against the enemy himself.

In more concrete terms, balancing these aspects involved toning the body by performing gymnastics, wrestling and swimming, simultaneously achieving harmony with nature by going with the surf, for example. To gain spiritual balance, lua warriors learned to chant and to hula. They ate a special diet and learned to breathe with measured inhalations and exhalations, much as yoga students do today.

To learn to think quickly and to strategically plan their moves, warrior students practiced konane, a Hawaiian game similar to checkers. They learned balance by kneeling with each foot on opposite sides of a halved gourd-the trick being to avoid breaking the fragile edges of the gourd. To achieve agility, the young warriors practiced weaving their bodies swiftly through tautly strung cords hung a foot apart.

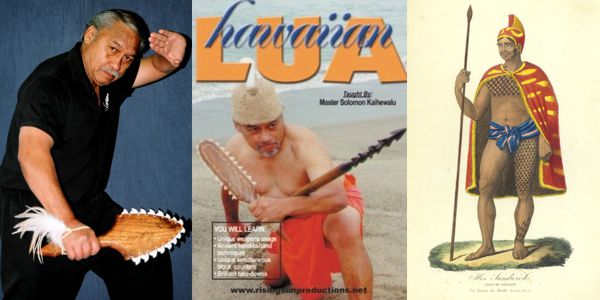

In hand-to-hand combat, King Kamehameha was reportedly the greatest Lua warrior of all. Besides being renowned for courage and strength, history carries tales of the king dodging and catching a dozen spears at once and lifting rocks that no others could. He and his warriors knew perhaps 300 moves that enabled them to break bones and dislocate bones at the joints without the use of weapons. They could inflict severe pain on their enemies by pressing on nerve centers. Similar to some martial arts practiced today, high leaps and kicks were also common in Lua. Warriors went into battle with their bodies oiled and their hair cropped short, so they could slip easily out of the grasp of other combatants. Battles usually ended with the death of one of the opponents.

By the end of the 18th century, King Kamehameha had acquired firearms, which brought him victory in his battles to unite the islands without resorting to hand-to-hand combat. In 1820, the kapu system was broken, disrupting a societal system that had insured the passing of Hawaiian traditions for generations past. Then, when missionaries appeared on the scene, the teaching of lua was looked upon with disfavor, and by the 1840s it was banned. Only a few Hawaiian families continued to practice the moves and pass the secrets of the discipline down to younger members. The art virtually disappeared.

In 1991, the Native Hawaiian Culture and Arts Program, with financial backing from the National Parks Service and from Bishop Museum recognized that lua was a lost tradition. A group of four men who had learned lua from a part-Hawaiian scholar named Charles Kenn back in 1974, began conducting classes on O’ahu, the Big Island, Maui, Kaua’i and Moloka’i. Named Pa Ku’ialua for the ring in which practice takes place, the group of men-Jerry Walker, Richard Paglinawan, Mitchell Eli and Moses Kalauokalani-have taught perhaps 300 Hawaiian men and women the moves involved in lua.

Lack of funding has curtailed some of the Neighbor Island classes, but Pagalinawan, age 61, continues to teach lua to about 65 part-Hawaiian students, 21 years or older on O’ahu at Kamehameha Schools and at the Queen Lili’uokalani Children’s Center.

Although the martial discipline seems no longer to be in danger of disappearing, few people have the opportunity to observe warriors in practice. Sham battles are sometimes staged at makahiki celebrations, as in days of old, or during special ceremonies held every August that commemorate of the unification of the Hawaiian Islands at Pu’ukohola, the heiau near Kawaihae.

As in ancient times, battle begins with chants that give way to insults, threats and gestures to show strength. The warriors begin their challenging haka, or dance, lunging and dodging from side to side. As the battle commences, unlike those of earlier times, it is not a fight ending in death, but an event that promises life-life for an ancient art that is just one more piece of the puzzle being assembled to save the Hawaiian culture.

Lua, the Hawaiian Art of Bone Breaking

By Betty Fullard-Leo