The skill of stick fighting and the use of sticks as handy weapons dates back to the beginning of mankind. The stick gained an advantage over the stone because it could be used both for striking and throwing. When dealing with martial arts, in many countries, there is a special place for fighters skilled in stick fighting. This includes India, China, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, countries of Africa, Europe, the Americas etc.).

The short stick is a handy weapon and has been used as a means of self-defense against animals and later against attackers. The short stick is better than the long stick primarily because it is easier to carry and use and therefore was a means of self-defense used in all countries of the world in long times past.

The main advantage of the stick over other weapons is its simplicity in handling. With the short stick one has the ability to apply techniques quickly in defense against one or multiple attackers, and the ability to keep the opponent at a certain distance. The short stick also allows easy transformation from a tool to a weapon.

Although the skill of fighting with the stick was well known all over the world as a martial art with a specific name, it has remained so in only a few countries.

In ancient Greece and Italy the use of the stick was more common with shepherds. The Romans used the stick for fighting, but it was not a skill that caught on. During the military campaigns of Charlemagne (768-814) European peasants also used the stick for self-defense. In feudal England the skill of short stick handling was a part of the education and upbringing of young men.

Fighting with the stick as the means of self-defense actually appeared in most of Europe after 1096 when the first Crusade began. There were some records of stick fighting in England. The legend of the fight between Robin Hood (Longsdale) and Little John (the skill called singlestick) comes from that time.

In the 16th and 17th century duels (fighting with the sword) as a way to solve conflicts became very common in Italy, Germany and England. However, the country with the largest number of duels was France. Historians confirm that during the period from 1589 until 1607 more than 4000 people died in such fights, mainly from the officer corps and aristocracy. During this time there were many of officers applying the stick for protection.

The stick had been known as a means of self-defense since ancient times. However, the stick’s use as a martial art began to spread throughout Europe around 1700 and eventually it became accepted as a means of self-defense, not only by farm men, but also by the aristocracy. This skill was most appreciated in England.

Consequently the European aristocracy from England, France and Switzerland, later in other parts of Europe eg Italy, Spain and Portugal, and less often in Germany, Scandinavia and Russia, used the stick as a handy means of self-defense.

The fight with the stick is called bataireacht in Ireland, while a similar fight in Spain is juego del palo (in Basque-makila), in Portugal jogu do pau, in Italy scherma di bastone and in Venezuela juego del garote. In England there are famous stick fights known as singlestick (cudgels) or quarterstaff from Berkshire… the fight with the stick is also called…

Japan (Kendo), India (Kalaripayattu), India-Sikhs (Gatka), Philippine (Arnis, Eskrima, Kali), Brasil (Maculele), Trinidad (Calinda), Japan (Bo-jutsu), Thailand (Krabi krabong), China(Gang), Korea (yong bong)…and many others.

The stick has gradually evolved from its first use as a means of self-defence into a part of aristocratic costume accessory and thus carrying the stick was considered gentlemanly

(walking sticks). The custom of stick carrying as a sword replacement survived with European aristocracy until the middle of 19th century, in some countries eg England and France stick carrying lasted until the beginning of 20th century.

Stick carrying was also fashionable in some colonial states in the Americas (the USA, Canada, Mexico, Brazil etc.).

Plenty of members of the aristocracy and bourgeois gentlemen used the stick for their own protection, however the value of the fighting skill itself as a national and traditional value was maintained in only a few countries in a modified and transformed way.

A good example of the value of stick fighting skill is in England around 1850 where this discipline was called cudgelling, backswording or most often singlestick. The skill’s aim was to counterbalance punching ie boxing. Nevertheless, this martial art didn’t become popular so it was only the police who trained in the art. Stick fighting in England was present in some boxing clubs at the beginning of 20th century as a part of self-defense training (bartitsu used a sturdy umbrella), but gradually stick fighting fell into oblivion.

In France around 1800, with the appearance of savate (French boxing), the practitioners started exercising with a short stick (la canne in French) or with a longer one called le baton

(a bit older and different kind of fight).

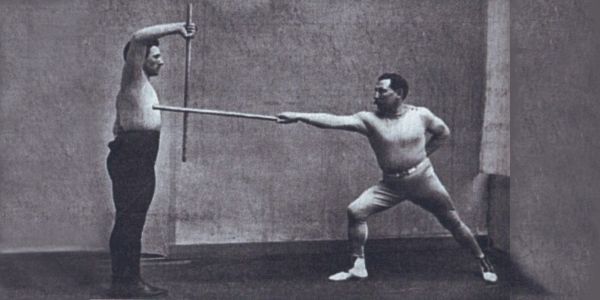

La canne was invented by French officers and noblemen in 18th century and they were the first to use it for self-defense. The stick replaced the sabre and the skill itself resembled fencing.

Unlike la canne, the martial art with a longer stick – le baton, came from peasants and shepherds. The same skill began to be used by many of the French citizens for self-defense in 17th century.

In 1817 a public demonstration of la canne was performed in the theatre Ville Lumiere (Paris). Since then the police started to practice it in Toulouse and Paris where a certain master called E. Vidoca was their instructor.

The first book about the discipline “Loze de Toulouse” was written by J. Le Boucher in 1850.

Later there were many savate masters systematized stick fighting skill la canne. Among the first masters to recommend it were E. Larribeau and C. Lecour. In 1845 Charles Lecour (1808- 1894) wrote the first manual on savate rules, presenting 180 techniques from la canne, as well. This martial art was also promoted by French masters G. Pavigneron and J. Charlemon (a savate promoter as well). It is said that round 1850 there were about 250 la canne instructors. The savate master Joseph Charlemon passed down his knowledge to his son Charles Charlemon who later became a famous savate and la canne master, as well.

It is important to mention Owen Swift and Jack Adams, the two masters of savate and la canne who showed exceptional knowledge in 1838, as well as one of the former leading masters of these martial arts Michel Casseux (1794- 1869).

Savate masters used another name for la canne discipline – canne chausson.

Another la canne promoter was a Swiss named Pierre Vigny (Paris 1866- Geneva 1917?), who taught bartitsu in London from 1901 to 1904. Unfortunately, Vigny modified and changed the la canne discipline by adding some elements of the English martial style of quarterstaff together with some procedures from the self-defense techniques of bartitsu (bartitsu-created by E.W. Barton-Wright). In 1920 the English officer Henry G. Lang taught elements of la canne discipline in India but again mixed with bartitsu variations.

Thanks to the savate master Charles Charlemont (1862-1944), savate, and therefore la canne skill, was introduced at 1924 Olympic Games in Paris. In 1900 the master A.C. Cunningham started teaching la canne in America, also, in 1940, the skill was taught by Charles Yerkov. At that time the famous master Roger La Fond taught the discipline in France.

Unfortunately during the period between 1924 and 1950 this martial art declined and the number of practitioners was drastically reduced. A few remaining masters wanted to save la canne skill and knowledge but, on purpose or not, they mixed various le baton techniques and joined them to la canne. The la canne skill, rather neglected and forgotten, came back between 1950 to 1970, rediscovered by the master Maurice Sarry (1935- 1994). He repeated the mistakes of his predecessors by combining certain techniques from le baton and bartitsu (quarterstaff) and mixing them with la canne (thus it is not the authentic form of la canne). Moreover, the skill of self-defense (the primary aim) got a new sport character.

The stick used in la canne skill is 85cm to 105 cm long (very rarely the length was from 80cm to 110cm). The best length regularly is 95 cm. The stick weighs between 150 and 300 grams depending on the material of which it was made. The stick used to be made of high quality wood, hard and shockproof (burned beech, oak or chestnut). The wood was often dried in order to achieve additional strength and resistance.The stick handle had mostly a spherical shape (Baroque stick) made of some metal like silver, ivory or gemstones, specially carved and ornamented. It was usually hooked to the stick by a brass or nickel ring with a screw for wood. Sometimes the handle was made in some animal forms eg duck, goose, lion, dog, horse, snake, eagle etc., in a certain form of hammer and even in a form of a devil. The human imagination used in the stick making was and still is astonishing.

The stick used in le baton discipline is 140cm to 170cm long. Very rarely it could be longer but not more than 180cm. The weight of the stick is 400 cm maximum. It had to be made of high quality wood, hard and shockproof but light as well. Almost all of the fighting techniques were performed so that the stick was held with both hands throughout the fight. This technique is very similar to the stick fighting techniques in Spain, Portugal, Venezuela and some African countries (the fighting technique with a longer stick held by both hands).

Some authors of articles on la canne as well as some masters claim that there are only 6 basic techniques mutually combined. Such a statement is not completely correct because some old fencing techniques are missing. The technique of la canne is unique in the world, and the la canne master has to know fencing technique very well, especially the discipline of the foil. There is also a certain la canne technique similar to the fencing technique with a sword called rapier (a long and pointed sword), the one known as rapier-sword style. The master of la canne must apply the old fencing technique, which is no longer used in modern fencing. It doesn’t mean that such a technique is wrong, bad or useless in self-defense. On the contrary, it has a century long tradition and has been used through countless ages in various situations. In fact savate and la canne were invented for only this purpose.

Nowadays la canne has a sport character so that there are many stick fighting competitions organized worldwide. The competitor’s goal is to give two strokes that the opponent can’t evade. The name of this discipline is – canne de combat. It uses a rather distorted la canne technique (an attractive and modern technique with plenty of jumps or vaults). Most sportsmen who practice la canne at present are not acquainted with savate technique. All in all, if you are interested in stick fighting you can take part in this sport.

It is interesting that currently there are more la canne experts, or those that claim to know a lot about it, in countries other than France, including in Portugal, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, Canada, Australia and the USA and even in Lebanon, Senegal, and Mauritius.

It can be said that the performance of la canne today is not authentic: from greeting the opponent to the taking of the initial position. Also both the defensive and offensive techniques are not authentic, consisting of a lot of jumping. The sticks that are used are diverse, some are too long, some are rounded in the upper part (so called shepherd or hooked sticks), others haven’t got the handle that suits the la canne discipline.

There are practitioners who perform le baton discipline attempting to reassure us that it is actually the same as la canne. They also exercise the use of two sticks (batons), or turn the stick round the arms like majorettes or circus artists (twirling). They neither know the basic elements of savate or fencing technique. What they do is certainly not la canne.

Today the highest quality sticks are made in Germany and one of the best kinds of wood for this purpose is American walnut (burnt walnut, particularly dried). Such a stick is more resistant to vibrations and more solid than others. Nevertheless, some masters want unique sticks even with a metal blade inside (sword–rapier).

Regardless of numerous variations while performing the sticking fight la canne, the skill itself is attractive for modern practitioners, the number of which is constantly growing. Among them are those who will help us rediscover the old authentic discipline of la canne and reintroduce la canne to the general public (eg Maurice Sarry : le secret “La Rose Couverte“). They will restore la canne’s luster and reputation, which it surely deserves, in the world of martial arts.

Finally, instead of conclusion:

EN GARDE – SALUT DES ARMES – BALESTRA – FLECHE – PASSATA – TOUCHE

David “Sensei” Stainko

Master of Kinesiology

7th Dan MMS