Kuntaw is an ancient art of native Filipino hand and foot fighting using both hard and soft techniques. It is one of the oldest self-defense arts devised by Filipino Muslim royalty prior to the Spanish regime. Long before the coming of the Spaniards to the Philippines, systems of unarmed (kuntawan) and armed (kali) fighting were being taught and developed. Kuntaw is a Filipinized term for the martial arts. However the type of kuntaw which was passed down to the lower classes of the country later on was accepted more as a national sport than as a fighting art.

Kuntaw is an ancient art of native Filipino hand and foot fighting using both hard and soft techniques. It is one of the oldest self-defense arts devised by Filipino Muslim royalty prior to the Spanish regime. Long before the coming of the Spaniards to the Philippines, systems of unarmed (kuntawan) and armed (kali) fighting were being taught and developed. Kuntaw is a Filipinized term for the martial arts. However the type of kuntaw which was passed down to the lower classes of the country later on was accepted more as a national sport than as a fighting art.

The particular styles of kuntaw practiced by Filipinos since the 14th century are considered a secret fighting art. There are two distinct arts involved in this, first sikaran, which deals alone in the use of foot techniques, second is kuntawan, which is the combination of hand and foot techniques.

“The art originally consisted of only soft, open hand techniques with emphasis on holding and locking while striking with either hand or feet”, explained kuntaw Grand Master Carlito A. Lanada. “After World War 11, the Japanese, Okinawan, and Korean arts came to the Philippines. This gave me an opportunity to see different hard styles of martial arts. I studied them, borrowed what I needed, and synthesized them into my own techniques. No one style contains all the answers nor a magic formula which can transform a weakling into human a fighting machine. What I did was revise the old to satisfy the new. I was willing to try something different in my school for the sake of my students to help them grow to his or her fullest potential. I chose to expand and modernize the art and added hard techniques to the style. This made kuntaw into a hard/soft style with avenues of response to any kind of attack.”

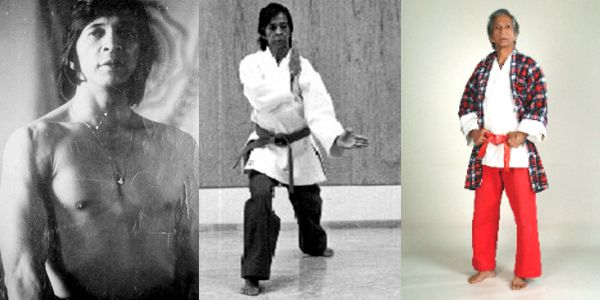

One has only to watch the 71-year-old martial arts master in action to realize the effectiveness of his art. At 5’ 5” his slight but firm physique, is very deceiving. Soft spoken and humble, Lanada moves like a snake or a tiger, depending upon which technique he is doing. Blinding fast kicks and punches land with incredible power and pin-point accuracy as he switches from soft blocks to hard counters in the blinking of an eye.

“In kuntaw, the study of vital points of the human body and how to him them is a special art in itself, which is called kuntaw sapol, meaning hitting the vital points,” said Grand Master Lanada. “These points are broken down into three categories: primary, secondary, and temporary. There are a hundred or more vital points in the human body, but many of these can only be reached by an acupuncturist’s needle. The points we emphasize are the easiest to get to and are where nerves, sensitive bones, breakable joints, and vital organs are located. An expert (dalubhasa) in this art can easily damage his enemy by just lifting his hands or feet to hit the vital point of the attacker.”

The history behind the Grand Master of this art is as fascinating as the art itself. As a young boy living in Japanese occupied Philippines during World War 11 Lanada was a guerrilla, fighting along side of his family and fellow countrymen.

The youthful commando was used as a messenger. Carrying vital information in hallowed out coconuts he repeatedly walked through Japanese camps ferrying top-secret orders under the enemy’s nose. Had he been caught, death and torture would have been a certainty.

For more than an hour I watched in awe as Grand Master Lanada executed technique-after-technique with his senior black belt Master Bud Cothern of San Diego California. It was truly martial arts poetry in motion.

“The man is amazing,” said Cothern about his teacher. “Can you believe how fast and powerful he is? After more than 20 years of watching and learning from him I am still in awe of his speed and power.”

Grand Master Lanada’s flawless form comes as much from a blood line as it does hard work and training. For it was his ancestors who founded the art of kuntaw during the time of Magellan and Spain’s rule over the Philippines. Forced to abandon their fighting art or be punished by law, Filipinos had to train in secret. The art was kept alive primarily in the southern Philippines until finally, following the ban of the Spanish occupation, a man by the name of Yuyong Henyo left Mindanao and moved to Luzon bringing with him the knowledge of kuntaw. Yuyo’s last name Lanyada was changed to Lanada per Spanish decree of having a Spanish surname.

“For centuries the deadly fighting art of kuntaw was passed from father to son,” said Grand Master Lanada. “When my grandfather, Amang Huenyo, left the island of Mindano and settled on Luzon he brought with him his knowledge of the art of kuntaw. He taught my father who in turn taught me and as legal heir I continue to pass on the art of kuntaw. The legacy of my ancestors will be kept alive through my students and family”.

In addition to the many punching, kicking, striking and sweeping techniques in kuntaw is the art of stick fighting. Arnis de mano-kali, “harness of hand”, is the best known and most systematic fighting art of the Philippines. Originally known as kali, arnis centers around three distinct phases: stick, blade, and empty-hand combat. As a fighting art arnis had three forms of play: espada y daga (sword and dagger), in which a long wooden sword and a short wooden dagger are used; solo baston (single stick) where a single long stick made of wood or rattan cane is employed. And sinawali, a native term applied because of the intricate movements the two sticks resemble the criss cross weave of a pattern used in walling and matting.

“Arnis/kali is most effective in close-range combat,” explained Grand Master Lanada. “In training we have three principal methods. One is the pansalag which teaches the artistic execution of the swinging movements and striking for offense and defense. The sanga at patama is next. Wherein the striking, thrusting, and parrying in a prearranged manner are taught. Finally the labanan totohanan, fighting for real. Kuntaw arnis has many different styles incorporated into it and has kept up with the modern arnis concept. Locks and takeaways are a major part of this art and lend themselves to be used in self-defense applications. Striking and parrying skills must therefore be developed with the utmost dexterity. The expert use of the legs to offset balance and throw an opponent must be perfected. Unlike other martial arts that make use of the entire body, early kali as well as modern arnis emphasizes the use of the stick and hand-arm movements. Many of the ancient techniques and weapons have been modified to prevent injury to students.”

As in other martial arts kuntaw also places a great deal of emphasis on internal power. This is accomplished through breathing exercises and meditation. According to Grand Master Lanada this is the true source of an individuals strength and must be exercised and trained properly and regularly.

“There are two kinds of strengths,” said Grand Master Lanada. “First is the outer physical strength, which fades with age. This strength is cultivated through exercise. Second is inner strength (kusog pang lo-ob), which is by far the most powerful of the two. The kusog pang lo-ob is a force within us all that can be performed by will power. No one can really explain the true kusog pang lo-ob, but it can be learned and performed through regular kuntaw training in combination with breathing techniques. It is not a process to be hurried. Much patience is required to develop this skill but it is well worth the wait and the effort.”

Overall the fundamental tactics and principles of the kuntaw style are very practical. There are no hidden movements or techniques in their forms. The purpose of each block, punch, kick or counter is well defined within the kata with an emphasis on excellent basics being the key to success.

“My goal in teaching kuntaw is not for offense but for defense,” explained Grand Master Lanada. “What I am trying to teach is street-wise self-defense. I am not grooming students to master the arts for exhibition or public display, but rather to learn self-preservation while improving yourself as an individual”.