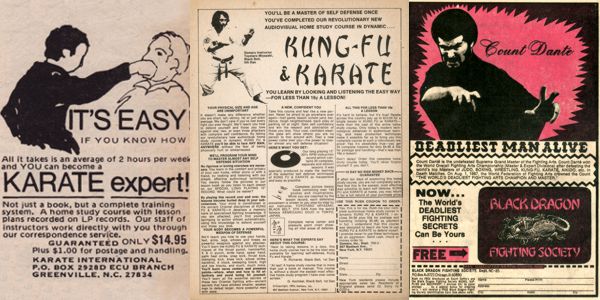

Flip open any martial-arts trade magazine, and you’ll find page upon page of ads for merchants selling instructional books and videos. Learn the ancient techniques of the Taoist sages! Let the grand champion Invincible Warrior™ personally show you how you too can be an indestructible force of nature! Just buy this book or video!

U.S. history alone is filled with stories of people who are self-educated men. No less a personage than Abraham Lincoln became a top-notch trial attorney simply by reading on his own. But is it possible to teach yourself a martial art through a book or a video?

No.

Like those silly ab machine infomercials, the promise of a complete martial art for less than $100 (plus shipping and handling) is a marketing ploy designed to play upon our fantasies of learning something worthwhile. This fantasy can be especially tempting to those of us who don’t live in or near a major metropolitan area and thus have few, if any, choices for martial arts instruction. In New York City or San Francisco or Los Angeles or Chicago, one has many style options and choices for martial arts teachers, and the odds are that you can find and actually train with several that are quite good and even world-class. But if you live in a sleepy farming community in Nebraska (for example), consider yourself lucky to find a single Tae Kwon Do school run by a guy who’s had maybe three years of actual instruction – tops. It’s certainly easier to believe that you can get the good instruction you want by sending away for some instructional materials than to believe that you have no real option if you want to learn something good by actually packing up your entire life and moving.

But that’s a fantasy. The sad fact is that books and videos are no substitute for actual instruction – and if you read the fine print in the books and videos, they’ll tell you the same thing. Training with a real instructor confers advantages that no video or book, no matter how well-produced, can match.

- Instant feedback. As you learn a technique or a skill, there are bound to be little details you miss and get wrong, no matter how assiduously you imitate the image on the page or screen. Over time, these details become ingrained as habits that can diminish the technique’s effectiveness or be detrimental to your health. But a live instructor can spot this and correct it – multiple times, if need be – before it becomes a habit that is difficult to correct.

- Student interaction. It’s all very well to be able to perform a technique in empty space, and another thing to execute it on an actual opponent. This seems obvious when we talk about grappling arts: you can approximate how your arms and legs would need to move in order to execute an arm bar from the underneath (guard) position, but you’ll never be able to do it for real unless you experience and learn how it feels to actually do it on a guy who’s resting his bodyweight on your ribcage, trying to shake your legs loose and choke or hit you with his arms – all at the same time. But it’s true for striking arts too. You can learn how to kick in the air, but do you know how to compensate your balance for when you’re kicking a live, moving target? How about when you miss that live, moving target?

Now, a lot of people figure they can get around this by recruiting a training partner who learns and practices off the book/video at the same time. It’s an admirable effort, but here’s the thing: a technique feels different each time you apply it on a different person. Doing a triangle choke on a tall guy with long wiry limbs presents different problems and opportunities than it does on a short, stocky muscular guy; same for a sweep or a parry. The only way to get a good feel on a technique is the practice it on as many different training partners as you possibly can.

As it turns out, one of the best places to find a large number of different training partners is – an actual school.

- Feel. With all due respect to the movies and films, the best martial arts can only be felt – not seen. A lot of this can be taught by having a live instructor and lots of training partners. But more importantly, it is learned by seeing a technique performed for you in person and feeling an expert perform it on you. Let’s take something a (seemingly) simple as a lead jab. We’ve all seen it done by boxers both pro and amateur. But what about the details? How does the weight and balance shift before, during and after a jab? What about the miniscule little tension-and-release interplay that goes through a boxer’s various arm muscles at the same period of time? What changes in your recovery if your opponent ducks, slips, or weaves? What about if you want to followup with a cross, uppercut, or kick? On a video, especially to a beginner, the differences are nearly indistinguishable. But with a live training atmosphere, you can truly develop an understanding of these issues.

In addition to these three advantages, a school offers a convivial social atmosphere and sense of comradeship that is not only nice, but can serve as a motivator: there have been days in which I made sure I trained because I didn’t want to fall behind relative to my peers. On other days, I went into class not because I was in the mood to train, but to hang out with my classmates. Either way, it definitely helped keep me disciplined.

Does all this mean that I think books and videos are useless in your martial arts education? Absolutely not. These materials can add a valuable component to your training.

- Deeper concepts and history. Sometimes it can be difficult or inconvenient for an instructor to sit down and pontificate at length about underlying philosophies and principles underlying the art. No one goes to wing chun class to learn about Confucius’s “Theory of the Mean” – they want to train and work drills and spar. No one goes into their Brazilian jujitsu class with the intent of hearing how social and political developments in Japanese history led to the development of grappling arts, then judo, before emigrating to Brazil. They want to get on the mats right away. But these concepts and history are important to their respective arts, and are not just more conveniently, but more clearly explained in a video or printed format than in an oral format.

- Differing perspective. Within a style, different masters can have a different approach and perspective to an art. This is natural, as each master learned to make the art suit his or her own needs, personality, and body structure. One has only to look at the Chen, Yang, Sun, and Wu styles of Tai Chih (Taiji) to see evidence of this – even though they each ultimately derived from the same source. The founder of the Wu style was taller and more interested in fighting, and developed and taught his Taiji to fit this profile. The Yangs wanted something that even the elderly could learn, so their form, while it still has some fighting aspects, became smoother and less taxing on the body. Sun Lutang was an accomplished master in two other arts, and his Taiji footwork and body movements were influenced by those other styles. And practitioners of the Chen style, the original Taiji style, were mostly caravan bodyguards and thus adapted their art to maim, injure and kill quickly so that they could defeat hordes of bandits on the dangerous roads of ancient China.

But I digress. Viewing videos or reading books by other masters of your style can thus give you a different perspective on a given technique and its uses, even if the underlying principles are the same. This can give you a fuller understanding of the principles themselves.

- Reference. Of course, books and videos can serve as a reference for advanced students who have inadvertently neglected or forgotten one class of techniques in their efforts to perfect their specialties. A periodic review of a good book or DVD can do wonders to refresh your memory and inspire you to get back to basics.

In an ideal world, everyone who wanted it would have access to a skilled teacher and receive live instruction. Unfortunately, this is often not possible, and many believe that books and DVDs can be an adequate substitute. They are not, and in fact can do more harm than good if they are used as a means of primary instruction. However, they can be useful in supplemental ways.