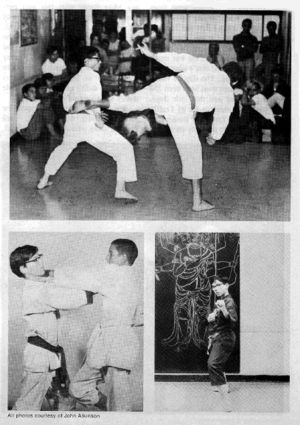

Johnny Atkinson’s name does not ring familiar to most of us today. He is an individual, though, who is known and respected by most of the great martial artists in this country who were active in the mid-70s because they fought him and knew his unbelievable ability and speed.

Johnny Atkinson is one of the true unsung heroes of the developing years of karate as a spectator sport. But today he is relatively unknown. A youthful looking 30-year old, Johnny has continued to teach through the years. His story is an unusual one about the precarious nature of fame in the business of martial arts.

John Atkinson was born in Boston, but moved to the Southern California area when he was two months old. This was a good turn of fate, for it put him in position to meet the people who would later affect his career as a martial artist. He lived in the Sherman Oaks area of the San Fernando Valley, as one of four brothers. He was small as a child, but he was encouraged by his mother to participate in all sports and excel. At barely more than five-feet tall, he made the varsity basketball team at Notre Dame High. He also loved to play softball with his brothers. They pushed one another to the limits of their skills, and instilled in Johnny a will to win.

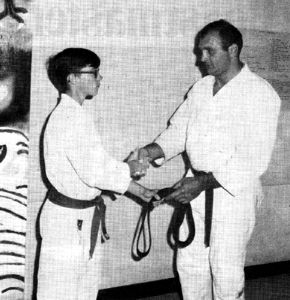

When he was 13 years old, Johnny walked into a small neighborhood karate dojo and was impressed with the art from the moment he saw it. The studio was owned by one of the true pioneers of karate in the U.S., Bob Ozman. Johnny enrolled in classes and there began a long and honored association between the two.”Bob, has remained my friend and instructor through the 17 years that I’ve known him. He’s really become more like a father to me.” says Johnny, of his teacher.

Bob Ozman saw a special quality in his five-foot, two-inch pupil. “He was very fast. He was one of the finest, natural athletes and most dedicated of student that I ever saw.”

Johnny’s test was no easy walk-through. Ozman pitted his student against a six-foot, three-inch, 200 pounder in self-defense techniques. To make things “fair” he gave the big guy a gun. “It wasn’t enough of an edge, though. Johnny succeeded in defeating even this opponent. He was awarded his rank by all judges.Bob worked hard with his young student, giving him the attention that his special abilities deserved. He saw in Johnny an ability and understanding that went beyond his age. And, so, when Johnny was 16 years old, Ozman suggested his student for the rank of Shodan. The group who was going to consider Johnny didn’t want to award him a black belt because they felt he was too young. If they so honored him, they said, he would be the youngest person in the nation to have a black belt, at that time. Bob insisted, however, that he be tested, “as an adult” and not in a junior division. He offered to put his young student up against any adult contender if he could defeat them he should be recognized at the full rank he deserved. Johnny didn’t disappoint his instructor. He competed in the ring with adults who were over twice his size and weight. At the time, remember, there were no weight divisions and no protective equipment. Johnny was awarded his Black Belt at full shodan, at age 16. Cecil Peoples, sparring great from the late 70s, recalls the day that Johnny was tested.” When I first met Johnny, it was 1967. It was at the Internationals; he was already a brown belt and he was beating everybody. He was much younger than me, and that’s what made him so interesting. The day he tested for his black, there must have been 250 people crammed into that little dojo. Everybody was there to see it. Traffic was stopped on Van Nuys Boulevard, because there were so many cars.”

Johnny’s test was no easy walk-through. Ozman pitted his student against a six-foot, three-inch, 200 pounder in self-defense techniques. To make things “fair” he gave the big guy a gun. “It wasn’t enough of an edge, though. Johnny succeeded in defeating even this opponent. He was awarded his rank by all judges.Bob worked hard with his young student, giving him the attention that his special abilities deserved. He saw in Johnny an ability and understanding that went beyond his age. And, so, when Johnny was 16 years old, Ozman suggested his student for the rank of Shodan. The group who was going to consider Johnny didn’t want to award him a black belt because they felt he was too young. If they so honored him, they said, he would be the youngest person in the nation to have a black belt, at that time. Bob insisted, however, that he be tested, “as an adult” and not in a junior division. He offered to put his young student up against any adult contender if he could defeat them he should be recognized at the full rank he deserved. Johnny didn’t disappoint his instructor. He competed in the ring with adults who were over twice his size and weight. At the time, remember, there were no weight divisions and no protective equipment. Johnny was awarded his Black Belt at full shodan, at age 16. Cecil Peoples, sparring great from the late 70s, recalls the day that Johnny was tested.” When I first met Johnny, it was 1967. It was at the Internationals; he was already a brown belt and he was beating everybody. He was much younger than me, and that’s what made him so interesting. The day he tested for his black, there must have been 250 people crammed into that little dojo. Everybody was there to see it. Traffic was stopped on Van Nuys Boulevard, because there were so many cars.”

After the event, Johnny continued to participate in tournaments whenever possible. Unfortunately, the important tournaments had to come to his area if he was going to compete. Of this Johnny comments, “We just didn’t have a lot of money, so I didn’t get to travel like some of the other guys did.” This is probably the single, most damaging factor in Johnny’s not gaining national recognition. The legendary Mike Stone puts this into perspective”. Johnny’s great talent was his quickness. He had a natural speed, he was a top competitor. But, at the time, there were many other good fighters who could travel. Johnny could win, but he wasn’t able to win consistently in the big tournaments because he didn’t get to them. People didn’t see his name often enough.”

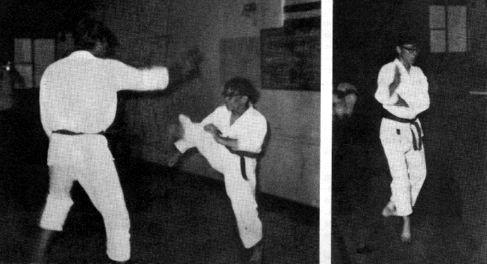

But when Johnny did compete, he was the center of attention. Cecil Peoples talks about this short-lived, small-scale notoriety. “The amazing thing was that he was so little. We didn’t use pads then, and there were no weight divisions. Every time Johnny was going to fight, they would stop all the other “matches” so we could all watch him. He was super fast!”

Johnny, for a short time, was given a chance to compete on a broader scale within the western states. He joined ranks with Bob Burbidge, Benny Urquidez and other fighters on a team that Mike Stone put together. One match in particular will go down in the annals of martial arts history. The moment came when Johnny Atkinson was pitted against Bill “Superfoot’ Wallace (former middleweight, world champion) in what Bob Burbidge calls “the most astounding match I ever witnessed.”

Johnny remembers them match well. “When they told me I was matched up against Wallace they all seemed excited, but I didn’t know who he was. This is probably good, because when they said that he had the fastest kicks around, I just wanted to show everyone that he didn’t.”

The match came down to a single point. Wallace decided to try and speed one of his famous front leg, roundhouse kicks into Johnny’s groin. Johnny responded with the same technique, but reached down deep for a little extra. His kick was to Wallace’s head. His speed was faster and he had beat Bill Wallace. Bob Burbidge continues the story. “The crowd went wild. Mike ran over and picked Johnny up to congratulate him. Johnny looked embarrassed. He didn’t know what he’d done. We were all happier than he was.”

Johnny is quick to point out that, although he sees himself as a fighter, kumite is not his only skill or interest in regard to karate. Besides a deep foundation in philosophy, he has a reputation as one of the fine kata champions of his time. Unbelieveable as it may sound, he actually beat Eric Lee, “the King of Kata” of today, in 1969 in Las Vegas.

Johnny is quick to point out that, although he sees himself as a fighter, kumite is not his only skill or interest in regard to karate. Besides a deep foundation in philosophy, he has a reputation as one of the fine kata champions of his time. Unbelieveable as it may sound, he actually beat Eric Lee, “the King of Kata” of today, in 1969 in Las Vegas.

“Kumite and kata,” Johnny says, “go hand in hand. One helps you develop in the other.”

John grew and expanded with his art, but did not compete with the regularity that he would have liked. He began to manage all three of the Ozman-ryu studios and this shackled him further from entering anything but local competition. He sadly found that his ability as a martial artist greatly exceeded his skills as a businessman when he bought one of the schools in the early 70s and it did not succeed. While it was still in his possession, he began to search for other avenues to blend his karate talents with the business of survival. Luckily, at this time, he was asked to play a small part in a new film that the Urquidez brothers were putting together. The film was entitled, The Fighting Gladiators. It was the usual socky-shlock, but the opportunity showed Johnny that there were other ways to remain in the martial arts and still make a good living.

Another break came for him when he was cast as an extra in the Rich Little film, Another Nice Mess, which was a satire on Nixon and Agnew. During the shooting of the film, the director decided to throw some karate into one scene. The result is a typically Hollywood “Cinderella” story. “By accident they discovered that I was a third degree Black Belt.” When they saw his ability, they were so impressed, they expanded the scene even further. So, what began as a background part, grew into a major segment for Johnny on the big screen.

Johnny was hooked now and began to study acting part-time, while offering his talents as a “hired-hand” to several studios, including Harold Gross, as a sparring instructor.

During one of these instruction sessions, a student not showing much control, kicked Johnny in the hand. A full year later one of his own students was slightly injured during class and Johnny wanted him to go for X-rays, to be on the safe side. The student cleverly agreed to go, but only if his instructor would also agree to get an X-ray. Both were examined. The student was fine. Johnny, however, was found to have a hand that was so badly broken for an entire year that it was near to total collapse. Today he retains a small, two-inch chip of plastic in his hand where bone used to be.

Johnny’s ability to ignore pain and adversity is one of the things which kept him going through the years as he watched his friends and equals rise to the top of celebrity, while his own career remained essentially stagnant.

But this story has positive highlights. Johnny’s life has been a relatively happy one. How many of us could boast of so many friends of such high caliber as Ozman, Urquidez, Stone, Burbidge and Peoples. Johnny relishes his triumphs and continues to help new fighters hone their skills. Ken Firestone, one of his proteges, was rated third at the Internationals this year. And, finally, his acting career may be blossoming due to his tenacity with the martial arts. One of his students, Tim Donnelly, former costar of the series Emergency, has gone into production with producer Brian Fong. They are casting Johnny in a lead role where martial arts play an integral part in the story. Does he think he’s up to the task of feature film acting? “I think So,” Johnny says, humbly. “Anyway, I appreciate the opportunity and I can only do my best.” If he does, noting his past records, we will probably be in for a very fine performance.

Johnny Atkinson passed away in 1999.

This article was first published in Fighting Stars magazine in October of 1982.