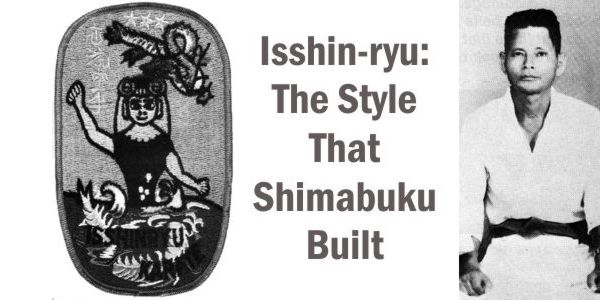

On January 14, 1956, Tatsuo Shimabuku went to sleep and had a vivid dream. In his sleep he saw a vision of a goddess, half woman and half serpent, rising up out of a churning sea. One of her hands she raised in a fist; the other she lowered and kept open, in a universal sign of peace and friendship. Above her it was night, and into the darkness her child, a dragon, ascended into the sky. When Tatsuo Shimabuku awoke the next morning, he was convinced that this dream had been divinely inspired. lt was on this day that he decided to break away from Okinawa traditional styles. He named his new system of karate, Isshin-ryu, (the one heart way). The images from his dream became the symbol of this new style.

So goes the legend of the genesis of Isshin-ryu, a martial arts method that has grown to become one of the most popular styles of karate in the world today. The reasons why this style has gained such popularity in such a short span of years, is as complex, yet as simple as the man who invented it.

The life of Tatsuo Shimabuku was one of total dedication to his beliefs. His story reads like a chapter to an ancient martial arts myth, for his whole life seemed to be guided toward the creation of Isshin-ryu.

The story of all Okinawan styles of karate begins sometime in the 19th century. According to one legend, a shipwrecked Chinese sailor, named Chinto, washed ashore on the island. He was naked, afraid, and without supplies in a strange land. He hid in some caves and at night went exploring. Finding villages, he stole the food he needed to survive. The villagers were, inturn, frightened by Chinto and went to their king for a solution. The king sent his best samurai, Matsumura, to take care of the problem. When Matsumura found Chinto he tried to subdue him with force, but the sailor blocked everything that was thrown at him. Chinto escaped and hid in a nearby cemetery. Matsumura returned to the king and told him that the problem had been taken care of; then he went back to the cemetery and befriended Chinto. He agreed to help the sailor if Chinto would return the favor by teaching him his martial art. In this way, all of the weaponless fighting systems are all supposed to have been derived directly from Chinto’s method.

In the Isshin-ryu style there is one kata that is named after this famous sailor. lt is said to have been taught to Matsumura by Chinto himself. Chinto kata was originally incorporated into the Shorin-ryu system by Chotoku Kiyan. Kiyan was Tatsuo Shimabuku’s first official teacher.

It’s important to note that most styles are able to trace their roots to some historical, mythical character who serves as an inspirational focus. In much the same way, the Buddha is at the heart of all forms of Buddhism, though many people who call themselves Buddhists believe differently than other sects. In this sense, all forms of Okinawan karate trace their origins back to Chinto. The main difference between other Okinawan styles of karate and Isshin-ryu comes in from what some call, “the second link.” At what point, after Chinto, were these various forms standardized? In all cases, except for Isshin-ryu, the originators are found far back in history hundreds of years. Isshin-ryu was developed over a long period, though as a separate style it was born less than 30 years ago. Isshin-ryu is therefore a true modern method based upon ancient traditions and techniques.

To understand his unique situation we should take a closer look at the history of Tatsuo Shimabuku who was born on Okinawa in 1906. Shimabuku’s uncle, Irshu Matsumora was a teacher of shuri-ti and lived in a village about 12 miles from his young nephew. In a rare discussion with some of his higher ranking American students, Tatsuo Shimbakru recalled his introduction into the world of karate. “I was eight years old. I walked the 12-miles distance to try and convince my uncle to teach me karate. When I talked to him, he spit on me and sent me away. The next day I returned and tried again. This time he threw a bucket of slop on me. The next day with a typhoon developing my uncle looked at me like I was insane and asked me why I had come back to him in such weather.” Finally, Tatsuo Shimabuku’s uncle agreed to his young nephew’s request, and so began a four-year casual course of study that consisted of doing menial jobs around the dojo and picking up what knowledge he could in his spare time. At 12, he became associated with Gajoko Chioyu, and was allowed to train formally in kobayashi-ryu. It was then also that he met Kiyan who was famous throughout Okinawa. Eventually Tatsuo Shimabuku became Kiyan’s leading student. About the same time, he met the originator of goju-ryu Chojun Miyagi.

To understand his unique situation we should take a closer look at the history of Tatsuo Shimabuku who was born on Okinawa in 1906. Shimabuku’s uncle, Irshu Matsumora was a teacher of shuri-ti and lived in a village about 12 miles from his young nephew. In a rare discussion with some of his higher ranking American students, Tatsuo Shimbakru recalled his introduction into the world of karate. “I was eight years old. I walked the 12-miles distance to try and convince my uncle to teach me karate. When I talked to him, he spit on me and sent me away. The next day I returned and tried again. This time he threw a bucket of slop on me. The next day with a typhoon developing my uncle looked at me like I was insane and asked me why I had come back to him in such weather.” Finally, Tatsuo Shimabuku’s uncle agreed to his young nephew’s request, and so began a four-year casual course of study that consisted of doing menial jobs around the dojo and picking up what knowledge he could in his spare time. At 12, he became associated with Gajoko Chioyu, and was allowed to train formally in kobayashi-ryu. It was then also that he met Kiyan who was famous throughout Okinawa. Eventually Tatsuo Shimabuku became Kiyan’s leading student. About the same time, he met the originator of goju-ryu Chojun Miyagi.

He devoted himself to learning the goju style, adapting quickly and becoming Miyagi’s best student. When Miyagi moved to China and on to Japan, however, the young Tatsuo Shimabuku was left without a master. So he returned to study the kobayashsi system, this time under the tutelage of Choki Motobua, legendary figure in his own right. It was under Motobu that Tatsuo Shimabuku’s talents finally came to full blossom. At a large martial arts festival in the village of Fatima, he entered the competition and virtually mesmerized the judges with his interpretation of Chinto-kata. He related a lesson to his advanced students about his experience in Fatima, “I was just a farm boy. Many people looked down on me because of the way I was dressed. It teaches us not to judge someone by their appearance, but by their abilities.” After winning recognition he studied the bo, sai and tonfa. His skills in weapons and empty-hand systems continued to gain him a greater reputation in the martial arts. This reputation was at its peak when World War ll struck the island.

Many Okinawans did not want to become involved in what they felt was basically a Japanese conflict. Shimabuku was a businessman and karate teacher at the time. At the very outset of the war his manufacturing plant was completely demolished leaving him bankrupt. He escaped conscription into the Japanese army only by fleeing to the countryside to work as a farmer. His reputation as a karate instructor had spread among the Japaneses soldiers, however, and they began a thorough search of the island for him. When some Japanese officers finally caught up with him, they consented to keep his whereabouts a secret only after he’d agreed to teach them karate. When the war was over, Tatsuo Shimabuku still saw little chance of earning a living in anyway except farming. Although he was now considered the island’s leading practitioner of both shorin-ryu and goju-ryu, he immersed himself in the study of karate only for his own spiritual and physical well-being. It was during this time that he began to experiment with new techniques in both weapons and empty-hand self-defense methods. Before this time the bo, for instance, was handled primarily from the left side. Tatsuo Shimabuku was the first to introduce the right side to equal and important use of the long staff.

Also, it was during this period of his life that he began to seriously consider the idea of a standard system of karate, combining elements from all the various styles. Tatsuo Shimabuku recognized problems that were developing out of the differences between styles, and how each style could be made more effective by joining its techniques with other methods. He consulted with the great teachers of his time, reasoning that the world had developed into a modern, technological and rapidly changing one, and a synthesis of styles was necessary to keep pace with new knowledge. Unification, Tatsuo Shimabuku felt, would enhance the growth of karate as a whole.

At first, there was general acceptance for his ideas, but later the leaders of the various schools began to fear loss of position and authority. If their particular system was no longer to be considered the best style by their students, would they still be considered masters? Soon, the idea met marked resistance. Tatsuo Shimabuku was forced to proceed on his own, and, after the night of the dream that was described at the beginning of this article Isshin-ry was finally given a name. Isshin-ryu, literally translated means, “one heart way.” As can now be seen, the name is particularly appropriate for a style based on the varied knowledge of a man who had dedicated his entire life to the study of karate.

At first, there was general acceptance for his ideas, but later the leaders of the various schools began to fear loss of position and authority. If their particular system was no longer to be considered the best style by their students, would they still be considered masters? Soon, the idea met marked resistance. Tatsuo Shimabuku was forced to proceed on his own, and, after the night of the dream that was described at the beginning of this article Isshin-ry was finally given a name. Isshin-ryu, literally translated means, “one heart way.” As can now be seen, the name is particularly appropriate for a style based on the varied knowledge of a man who had dedicated his entire life to the study of karate.

The style that Tatsuo Shimabuku developed drew heavily from both shorin-ryu (about 80 percent) and goju-ryu (about 20 percent) but skillfully blended the fluidity of shorin-ryu with the powerful striking force of goju. Tatsuo Shimabuku’s understanding of the benefits of the various techniques is better seen in some of the more subtle changes that he introduced into the martial arts. For instance his was the first style to place the thumb on the top of the fist instead of the side. Also, he was not convinced that there was any noticeable advantage to the traditional “twist” punch. He examined the structure of the muscles in the arm and concluded that a punch would be stronger if the fist remained vertical. Also, it was his view that such a punch could be retracted more quickly and without the danger of elbow breaks.

At first, even Tatsuo Shimabuku was reluctant to teach this new method of punching, feeling that the amount of controversy that might be stimulated made such a move unwise. However, bending to criticism was never Tatsuo Shimabuku’s style. He believed that there was a higher power guiding the development of “the one heart way.” He had no choice but to do what he felt was right. Of this he is recorded to have said, “A goodness exists inside my heart. God put this goodness there. It caused me to create Isshin-ryu. We aren’t doing this by ourselves. God is doing it.”

Eventually, this new method of punching was fully adopted by many styles. Today, most tournament fighters would not consider punching in any other way. In fact, many of the ideas that Tatsuo Shimabuku labored his entire life over which we reconsidered innovative and even visionary are now considered commonplace and obvious changes, necessary for karate to keep pace with an ever-changing world.

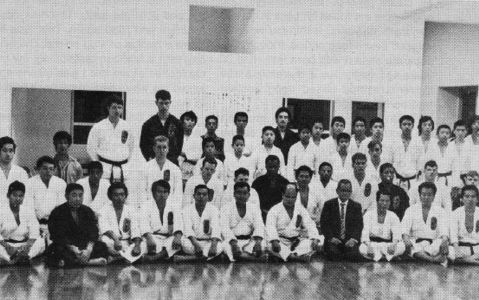

Tatsuo Shimabuku, who was known for his graphic descriptions often compared the training of a karateka with the creation of a fine piece of wood work. This comparison could also be made with the development of a whole style of karate. In this, the first step is the selecting of the wood, the cleaning off of the bark on a rough tree. The student learns, according to his ability, some basic stances and moves. The foundation is laid. The second step is like shaping the wood. During this stage the student demonstrates his willingness and his seriousness. Many are eliminated at this time.The third stage is like the sanding and molding of the wood. The student refines his techniques and may receive the rank of Black Belt. The final stage is like a continual polishing and waxing of the wood. This stage lasts a lifetime. The student begins to understand the Code of Karate (Kempo Gokui) which is the “innermost meaning,” in his own terms. This ancient code constitutes an attitude toward all life, and should be undertaken, according to Tatsuo Shimubuku, only after the student has learned all the kata and entirely devoted himself to the study of karate. In the late 1950s Tatsuo Shimabuku again became a forerunner of modern thinking. He began to accept a great number of serious non-Asian students into his Okinawan dojo. When these students became competent they returned to their homelands, including the United States, and helped to expand the innovative concepts of Isshin-ryu. The Federation of lsshin Ryu was established and grew rapidly as a worldwide organization, and Tatsuo Shimabuku, who traveled throughout the world to promote his philosophies, began to age. As is customary in Okinawan societies, he started to look for a successor from within his own family to carry on the traditions after he was gone. He didn’t have to look far, for his eldest son, Kichero, and his son-in-law, Angi Ueza, had fully adopted the responsibilities of the federation. They traveled along side the founder as well as alone to keep the global network of Isshin-ryu schools on an even basis of competency.

Tatsuo Shimabuku, who was known for his graphic descriptions often compared the training of a karateka with the creation of a fine piece of wood work. This comparison could also be made with the development of a whole style of karate. In this, the first step is the selecting of the wood, the cleaning off of the bark on a rough tree. The student learns, according to his ability, some basic stances and moves. The foundation is laid. The second step is like shaping the wood. During this stage the student demonstrates his willingness and his seriousness. Many are eliminated at this time.The third stage is like the sanding and molding of the wood. The student refines his techniques and may receive the rank of Black Belt. The final stage is like a continual polishing and waxing of the wood. This stage lasts a lifetime. The student begins to understand the Code of Karate (Kempo Gokui) which is the “innermost meaning,” in his own terms. This ancient code constitutes an attitude toward all life, and should be undertaken, according to Tatsuo Shimubuku, only after the student has learned all the kata and entirely devoted himself to the study of karate. In the late 1950s Tatsuo Shimabuku again became a forerunner of modern thinking. He began to accept a great number of serious non-Asian students into his Okinawan dojo. When these students became competent they returned to their homelands, including the United States, and helped to expand the innovative concepts of Isshin-ryu. The Federation of lsshin Ryu was established and grew rapidly as a worldwide organization, and Tatsuo Shimabuku, who traveled throughout the world to promote his philosophies, began to age. As is customary in Okinawan societies, he started to look for a successor from within his own family to carry on the traditions after he was gone. He didn’t have to look far, for his eldest son, Kichero, and his son-in-law, Angi Ueza, had fully adopted the responsibilities of the federation. They traveled along side the founder as well as alone to keep the global network of Isshin-ryu schools on an even basis of competency.

On May 30, 1975, Tatsuo Shimabuku died. Due to the efforts of his son and son-in-law, and the basic intelligence of the Isshin-ryu system his memory has every likelihood of surviving for a very long time. On January 12, 1980, a bronze bust of Tatsuo Shimabuku was placed in the main dojo in Gushikawa City where Kichiro is now in charge. Kichiro said that the statue is an exact replica of his father’s likeness and inspires him to “succeed and continue his will and intentions.” Hundreds of years from now, when many new styles of karate have been created and perhaps faded into oblivion, karate students will gaze at this statue and wonder if the tales of a young farm boy walking 12 miles in a typhoon to be allowed to study karate are true. They will probably wonder if this simple, peaceful-looking man could have really developed a system of karate called Isshin-ryu, based on symbols in a dream. The only evidence they will have will be a statue and an emblem of a goddess, rising out of a churning sea, giving birth to a dragon.

This article first appeared in Karate Illustrated in August of 1982 and was written by Gordon Richiusa and Bob Ozman.