Hop Gar kung fu is rooted in the Buddhist monasteries of Tibet. Buddhist monks spread the seeds of this ancient art from Tibet through southern China. These spiritual masters developed an understanding of both mind and body through the practice of meditation. It was in this state of consciousness that Hop Gar was conceptualized.

While meditating beside a mountain stream, a Tibetan monk observed a crane and an ape fighting. The ape attacked quickly using powerful circling blows intended to crush the defenses of it’s opponent. The crane moved gracefully in and out of range evading the ape’s outstretched arms. With speed and precision, the crane used its beak and wings to strike openings in the ape’s attacks. The ape was struck in the eye by the crane’s beak and ran into the jungle. Inspired by the techniques and power of the crane and ape, the monk developed an overwhelming martial art he called Lion’s Roar, named after the breath of Buddha.

During the rein of the Ming dynasty, the Chinese oppressed the Tibetan, Mongolian and Manchurian peoples. Being the minority, they were used as cheap labor and were looked upon as third class citizens. They were not afforded the same rights as the ruling majority peoples, the Han. In 1644, the Ming dynasty was overthrown by the Manchurians, thus beginning the Ching dynasty. For the next 276 years, rebellion swept the country.

The Shaolin sect of Buddhism, being Han, aligned themselves with the Ming supporters. The Shaolin Temples became the training ground for Ming rebels. There were two main temples. The northern and original temple is located in Henan province. The southern temple was located in Fujian province. Branch temples were organized in remote areas.

It was in this political climate that the Ching emperor allied himself with the Tibetans. The Tibetan monks were renowned for their fierce fighting style. Fearing a return to depravity under Ming rule, the Tibetan King offered their fighting skills to the Ching emperors. Monks came to the Ching court as teachers, not warriors, refusing to engage in combat. They trained the imperial guards and assisted in protecting the emperors.

Late in the 1860’s, a Tibetan monk named Sing Lung was traveling in the Canton region of southern China. While walking in the countryside, he happened upon a young man practicing kung fu. He quietly watched as the young man went through his routine. Sing Lung returned every day for several weeks to watch. He would sit quietly for hours observing the young man’s practice. In need of a guide and impressed by the young man’s dedication, he approached and introduced himself. The monk offered him a deal; kung fu lessons in exchange for guide services. The young man was offended by the offer. He arrogantly asked what the monk knew about kung fu. Sing Lung asked the young man to strike him. He tried and was discarded with ease. Several times, he attacked the monk only to be thrown aside. Sing Lung evaded punches and kicks with the grace of a crane, then attacked with the power of an ape, destroying his opponent’s defenses. Sing Lung took his balance by continually moving forward against his attacks. The young man named Wong Yin Lum (a.k.a. Wong Yan Lum) became Sing Lung’s student and companion.

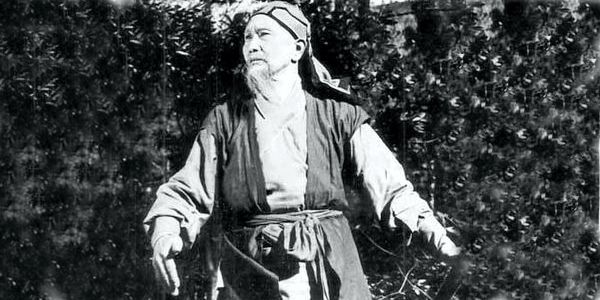

Wong Yin Lum was a master swordsman and master of Lion’s Roar kung fu. He became a personal bodyguard, escorting rich families and dignitaries through southern China. At that time, bandit tribes ruled the countryside. He was known for his lightning speed and powerful hands. He was highly paid by those who wished to reach their destination alive. He came to be known as master Hop (Cantonese for Knight).

Wong Yin Lum is famous for challenging China’s masters to join in a kung fu tournament. He had an open-air stage built in Canton to display his skills for prospective students. Wong Yin Lum planned to open a kung fu school and needed money. This would be the perfect arena to popularize his name. He also expected to make a lot of money wagering on the fights. For one week, he fought all challengers, defeating each opponent decisively.

He moved forward taking his opponent’s balance. Then he destroyed their defenses with powerful blows. Master Wong defeated 150 opponents and then was declared kung fu champion of China. He organized a group of the ten best kung fu masters in southern China. They were called the Ten Cantonese Tigers. Master Wong was the number one tiger.

Wong Yin Lum had two senior disciples, Wong Lum Hoi and Choy Yit Gong. Wong Lum Hoi assisted Grandmaster Wong with running the school. The school was popular and made a living for Wong Lum Hoi and himself. Choy Yit Gong was from a wealthy family and was not interested in teaching. He would later achieve fame as the bodyguard of Dr. Sun Yat Sin, the leader of the Nationalist party of China and was the man responsible for the overthrow of the last emperor of China.

Late in his years, Grandmaster Wong was almost blind and no longer taught. Wong Lum Hoi taught classes and supported Grandmaster Wong. He was considered to be a great kung fu master as well. Wong Lum Hoi had very little time to spend with Grandmaster Wong who lived by himself just outside of town. It was at this time, my teacher, Ng Yim Ming, became a student at the school.

Ng Yim Ming’s family had no money, so at the age of four, he had been given up to a local Peking opera troop. He grew up on the road learning acrobatics, kung fu and acting. Even at an early age he displayed an incredible talent for kung fu. He was fast, agile and flexible. His movements were elegant and flawless with explosive power.

In 1920, at twenty years old, he enrolled in Wong Yin Lum’s kung fu school. He would go to school in the morning, practice in the afternoon, then perform in three evening shows. The years of pain and hard work in the opera had prepared him well for what was to follow.

Wong Lum Hoi taught as much kung fu as his students could afford. Ng Yim Ming not having much money was taught few moves, which he practiced repeatedly while the other students advanced. He never complained and mastered what he was taught. Wong Lum Hoi would send him on errands and have him clean the school as the others trained.

Wong Lum Hoi started sending Ng Yim Ming with food and medicine for Grandmaster Wong. Grandmaster Wong was put off at first, but, he was lonely and he began looking forward to Ng Yim Ming’s visits. They would sit for hours and talk. After a short time, they developed a close relationship.

One day Grandmaster Wong asked Ng Yim Ming to show him what he had learned. Ng Yim Ming asked how the old man would see his kung fu. Grandmaster Wong said he could hear his movements and feel their power. After a few moments, he stopped Ng Yim Ming saying he had learned only a small amount of White Crane. Grandmaster Wong told him to continue going to the school during the day, and then come by his house after nightfall. Ng Yim Ming would spend mornings at the school and evenings performing in the opera. After the last show, he would practice with Grandmaster Wong until three in the morning. This kung fu was not what he had learned at the school. He asked Grandmaster Wong what was the name of this style. Grandmaster Wong had not been given a name for the style. Grandmaster Wong asked Ng Yim Ming to call it Hop Gar, meaning Family of the Knight. Ng Yim Ming studied with Grandmaster Wong for eight years.

Ng Yim Ming joined an opera troop traveling through southern China in 1928. His mastery of kung fu made him an instant star. He dazzled the crowds with great feats of kung fu and acrobatics. His speed and precision were without equal. He had mastered Hop Gar and was making extra money by competing in the streets. He was known as crazy Ming due to his brutal fighting style.

He stayed with the opera troop until 1935, when he moved to the United States. Late in 1938, he joined a group of men being trained as pilots to fight the Japanese in China. This group of pilots later became known as the famous Flying Tigers. He became a fighter pilot flying missions over the south of China. He joined the Chinese Nationalist Army Air Corps in 1941 and worked his way through the ranks to colonel. After the Japanese were defeated, he became the personal pilot and bodyguard of my father, General Ku Ding Haw. They became close friends over the next four years.

In 1949, the Communist forces led by Mao Ze Dong defeated and exiled the Nationalist sympathizers. We went to Hong Kong along with millions of other refugees. I had been learning Choy Lay Fut since the age of seven from Grandmaster Fong Yu Su, but I was forced to quit when we left China. Ng Yim Ming came to our house often for dinner parties. It was at one of these parties that my father asked him to take me as a student. My mother died when I was young and my father was away at war. I was raised by my grandparents and had become arrogant and spoiled. My father hoped Ng Yim Ming’s strict training style would help shape my character.

Ng Yim Ming trained in the tradition of the old masters of the opera. The student was required to live with and work for the master. Ng Yim Ming was reluctant to take on this responsibility, but felt he owed it to my father. In 1950, at the age of 12 years old, I became the student of Ng Yim Ming. My father was always gone on business, so we had never been close. Over the next few years we saw each other less frequently. Ng Yim Ming became my father.

We were often in the company of his best friend Law Wei Jong. He was a Shaolin monk who lived in the Ching Yuan Si monastery on Ding Wu Mountain near Canton. It was a branch of the Fujian Shaolin temple. Law Wei Jong was a scholar and master of many skills. He was an accomplished artist and calligrapher. He was a doctor of herbal medicine and a kung fu master. He represented the monastery when dignitaries would visit, acting as diplomat and guide.

In 1910, a high ranking Tibetan monk visited the temple. He was an elderly man about 100 years old. The monk’s name was Sing Lung. He had come to visit his old friend, the Abbot (head monk). Law Wei Jong acted as escort for Sing Lung. In appreciation, Sing Lung taught him the “Great Five Elements” chi kung exercise.

Ng Yim Ming escorted a lady friend to Ding Wu Mountain once a week for worship services. It was in 1946, on one of these trips that Ng Yim Ming met Law Wei Jong. Every week they would sit, drink tea and discuss philosophy, politics and kung fu. Over the next three years they developed a close friendship. Law Wei Jong left China in 1949, as did Ng Yim Ming never to return.

Ng Yim Ming was a hard teacher expecting all of my time and attention. I awoke at 5:00 a.m. and trained from breakfast until 7:00 a.m., then from 8:00 a.m. until 9:00 p.m. I trained, taking breaks for lunch and dinner. Ng Yim Ming was very secretive about training. If anyone except Law Wei Jong came to our house, we stopped training until they left. Often I would fall asleep only to be awakened after a guest had left to resume training.

Training consisted of forms, meditation, and iron robe. I punched rock filled bags. I beat my body with a bundle of chopsticks. I kicked trees until my legs were bruised and bleeding. We would apply some of Law Wei Jong’s herbs, and I would be kicking trees the next day. Ng Yim Ming would teach me a move, then send me out in the streets to fight. If I lost I would have to train twice as hard, so I learned not to lose. I would join a kung fu school only to defeat it’s teacher, then collect twice my money back to leave. Ng Yim Ming said Hop Gar was a fighting art and must be learned by fighting.

Life was hard in the Peking Opera business of 1950’s Hong Kong. We did not have much money. In 1958, at the age of nineteen, my uncle got me a job as a policeman with the Royal Hong Kong Police Department. Within three months, I was appointed the department self defense instructor. I maintained this position for twenty-one years. I spent five years as a policeman, then sixteen years as a civilian. I quit the police department to become a fireman. After four years, I left to become a bouncer. I found I could make more money in the nightclubs of Hong Kong.

In 1959, after nine years together, I became Ng Yim Ming’s disciple. In 1966, we opened the Hong Kong Hop Gar Kung Fu Headquarters. At the same time, I was learning herbal medicine from Law Wei Jong. We would workout early in the morning, then I would teach at the police academy until noon. I would go to San Shing temple after lunch to work in the clinic. San Shing temple was founded by Law Wei Jong in 1960. I would arrive at the school in the early evening and lead the school exercise until 9:30 p.m. I had to be at the nightclub by 10:00 p.m. and work until closing.

In 1970, Ng Yim Ming left Hong Kong to start a business in San Francisco. I remained in Hong Kong to run the school until I could get a visa from the United States. Ng Yim Ming had a school in San Francisco for about a year and a half. In 1972 he was shot and killed.

I moved in with Law Wei Jong after the death of Ng Yim Ming. I became his disciple in 1973. Over the years from Law Wei Jong I learned the 72 Shaolin kicks, Chin Na, weapons and hand forms. He taught me several chi kung exercises. Of these, the most important was the “Great Five Elements”. Law Wei Jong died December 26, 1989, in Hong Kong at the age of 108.

In 1981, I moved with my family from Hong Kong to Atlanta, Georgia. I opened Ku’s Holistic Health and Martial Arts Center. Currently, I have a Chinese herbal and pressure point therapy office where I specialize in bone and muscle injuries. I continue to teach by appointment and serve as Hop Gar Kung Fu Grandmaster. KU CHI WAI. Ku Chi Wai

As told by Grandmaster Ku Chi Wai