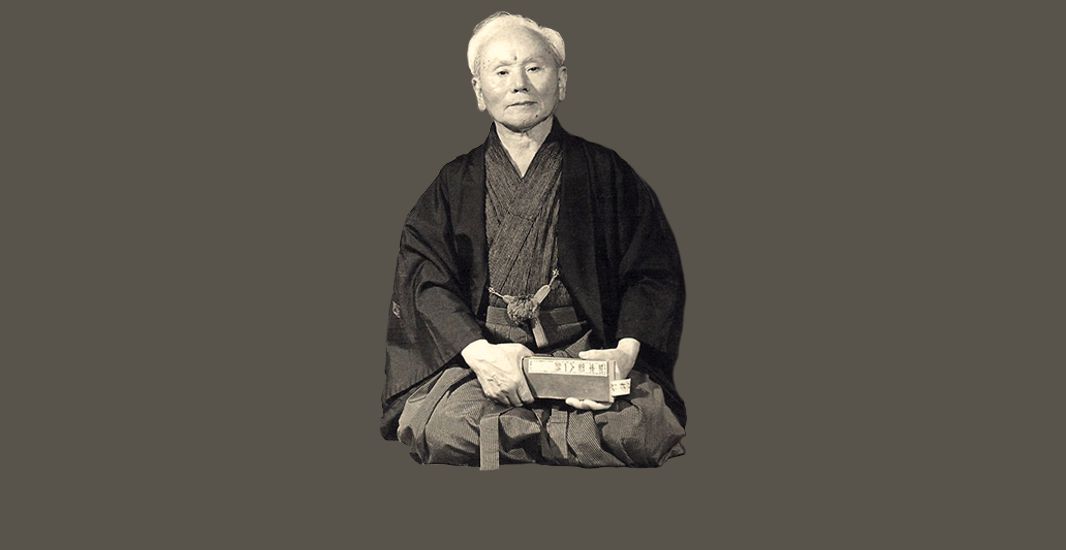

The great karate master Gichin Funakoshi was a key pioneer in the development of modern karate. In fact, he was the “prime mover” in bringing traditional Okinawan karate to Japan. He himself was caught in the great wave of social change sweeping through Japan and its prefectures. His contributions include authoring several of the first publications describing the previously secret art of karate, strengthening the connection between character development and karate training, and the development of modern teaching methods. Master Funakoshi supported the realization that karate would evolve from a provincial fighting system to a prominent member of the modern Japanese martial arts.

Stirrings of Change

Funakoshi was born at the beginning of the Meiji Period (1868), a period of considerable change throughout Japan. Meiji means “Enlightened Rule” and with the reigns of power transferring from the Shogun back to the Emperor, modernization and social change became the order of the day. This was a time of considerable social change and exposure to new ideas. This period led to a new view of Japan in the modern world.

Because Funakoshi reached adulthood during this volatile period, he had great opportunity to witness and consider the nature of change within society. By his actions, Master Azato, one of Funakoshi’s primary teachers, demonstrated his insight regarding change during this period. Azato demonstrated his support for change by cutting his topknot off when they were first declared illegal. This enlightened view toward the reforms of the Meiji Period probably influenced Funakoshi.

The clandestine practice of karate persisted through the early years of Meiji. This would change also. Karate was about to come out of the dark and into the light of day. It didn’t take long before many prominent and influential members of society took notice of karate and its virtues. This departure from secrecy to open contribution to society should be viewed in the context of social changes brought on by the Meiji Period. Karate was being changed from merely a fighting art to an art which improves human beings through rigorous and challenging endeavor.

The value of karate as a means of self-improvement was a key point which Funakoshi became expert at describing when lecturing about karate. He widened the scope in regards to who should practice karate. He stated that karate “should be simple enough to be practiced without undue difficulty by everybody, young and old, boys and girls, men and women.” His opinion that karate training can contribute to both mental and physical health must have some genesis in his recovery from poor health during early youth. He further described benefits of practice in the following way. “Karate-do is not merely a sport that teaches how to strike and kick; it is also a defense against illness and disease.” Because of this way of viewing the value of karate, it began to make the all-important transition from jutsu (technique) to do (way).

One of the areas were Funakoshi exhibited a pioneering outlook was in his appreciation of different styles of martial art. Azato demonstrated an open mind toward the other martial arts by encouraging Funakoshi to study them also. There was considerable rivalry between some of the schools of karate, with some claiming superiority due to their Chinese influence (ch’uan fa) and others claiming superiority because of their Okinawan heritage (tode). One of the chief areas of contribution by Funakoshi was to look beyond this situation of inter-style competitiveness and seek a synthesis of the best aspects from the different styles.

Given the open minds of his two primary instructors, Azato and Itosu, Funakoshi was in an ideal position to appreciate the strong points of the various styles of karate and begin integrating them together. He had been exposed to the different styles of the two masters, Shorei through Azato and Shorin through Itosu, and had trained with many of the other prominent Okinawan karate masters of the day. Funakoshi had become the most eclectic karateka of his day.

A Period of Transition

Karate was to undergo an important transition during the Meiji Period. It was time to evolve away from its secretive and lethal past and move into a new phase of public interest and contribution to society. It was perceived that karate had much to offer to a rapidly changing society during the upheaval created by Meiji Period reforms. In fact, the public’s interest in karate was aroused by several key events during this new phase of development.

The commissioner of public schools, Shintaro Ogawa, strongly recommended in a report to the Japanese Ministry of Education that the physical education programs of the normal schools and the First Public High School of Okinawa Prefecture include karate as part of their training. This recommendation was accepted and initiated by these schools in 1902. So began a long, fruitful, and continuing relationship with the educational system. Funakoshi recalls that this was the first time that karate was introduced to the general public. Thereafter, karate was successfully incorporated into the Okinawan school system.Gichin Funakoshi

To what extent did Funakoshi, due to his background and personal familiarity as a teacher within the Okinawa educational system, play a part in this development? It seems evident that this new policy demanded an even-handed, unbiased approach to representing and teaching karate so nobody was offended by omission. Funakoshi performed the task of primary spokesman for Okinawan karate with the capability of a seasoned diplomat.

To what extent did Funakoshi, due to his background and personal familiarity as a teacher within the Okinawa educational system, play a part in this development? It seems evident that this new policy demanded an even-handed, unbiased approach to representing and teaching karate so nobody was offended by omission. Funakoshi performed the task of primary spokesman for Okinawan karate with the capability of a seasoned diplomat.

Some years later, Captain Yashiro visited Okinawa and saw a karate demonstration by Funakoshi’s primary school pupils. He was so impressed that he issued orders for his crew to witness and learn karate. Then, in 1912, the Imperial Navy’s First Fleet, under the command of Admiral Dewa, visited Okinawa. About a dozen members of the crew stayed for a week to study karate. Yashiro and Dewa were thus responsible for the first military exposure to karate and brought favorable word of this new martial art back to Japan.

During the years 1914 and 1915, a group that included Mabuni, Motobu, Kyan, Gusukuma, Ogusuku, Tokumura, Ishikawa, Yahiku, and Funakoshi gave many demonstrations throughout Okinawa. This practice would have been quite unheard of during the earlier period of secrecy. It was due to the tireless efforts of this group in popularizing karate through lectures and demonstration tours that karate became well known to the Okinawan public.

In 1921, the crown prince Hirohito visited Okinawa. Captain Kanna, an Okinawan by birth and commander of the destroyer on which the crown prince was traveling, suggested that the prince observe a karate demonstration. Funakoshi was in charge of the demonstration. This was a great honor for Funakoshi and further established him as a prominent champion of Okinawan karate. It was shortly before the crown prince’s visit that Funakoshi resigned his teaching position, but maintained excellent relations with the Okinawan school system.

It was the Japan Department of Education which, in late 1921, invited Funakoshi to participate in a demonstration of ancient Japanese martial arts. In order to make the greatest impression, something more than a demonstration was called for. With significant assistance from Hoan Kosugi, the famous Japanese painter, Funakoshi published the first book pertaining to karate, Ryukyu Kempo: Karate. This book was forwarded by such prominent citizens as the Marquis Hisamasa, the former governor of Okinawa, Admiral R. Yashiro, Vice Admiral C. Ogasawara, Count Shimpei Goto, Lieutenant General C. Oka, Rear Admiral N. Kanna, Professor N. Tononno, and B. Sueyoshi of the Okinawa Times.

Soon, Funakoshi was balancing his time between early university clubs (such as Keio and Takushoku), a main dojo, and speaking and demonstration requests. His age ranged from 50 to 60 over this period — he was supposed to be approaching the autumn of his life and was instead introducing karate to Japan!

Funakoshi’s background as an educator was helpful for presenting ideas in concise and systematic fashion. Funakoshi pioneered the organization of karate instruction into three fundamental categories of practice: kihon, kata, and kumite. In fact, practice of kumite was rather new and aroused great enthusiasm among the young university students. Competition between university karate clubs helped fuel the interest in kumite and the popularity of karate.

Once in Japan, the universities became fertile ground for karate study. Was this also a result of Funakoshi’s educational and intellectual background? Was it because karate represented a wonderful blend of physical and mental challenge, combined with a sense of tradition and history? The popularity among the intellectually inclined was very fortunate for karate. The university groups helped transform karate from a mysterious, arcane art to a scientific martial art and modern sport.

Master Jigoro Kano, the father of modern judo, was instrumental in acknowledging karate as a valued Japanese martial art and in encouraging Funakoshi to stay in Japan. Even several sumo wrestlers became students of karate-do during this early period. They clearly recognized a noteworthy and potent martial art. During a period where Funakoshi wasn’t able to use floor space at the Meisei Juku, H. Nakayama, a great kendo instructor, offered Funakoshi the use of his dojo when not in use.

Later, the time came when constructing Funakoshi’s own dojo was ripe. About 1935, supporters gathered sufficient funds to construct the first karate dojo in Japan and in 1936 it was dedicated as the Shoto-kan. By now, many initial students who trained with Funakoshi earlier and had moved to other cities due to work, had also created a demand for instruction throughout the country. With the acceptance of karate by other established martial arts and with a growing number of dedicated students, the introduction and popularization of karate in Japan was now well underway.

Important Influences

Funakoshi was an advocate of karate’s health benefits. His strong conviction that karate training can enhance physical health must have been influenced by his dramatic recovery from poor health during early youth. Funakoshi may have subconsciously realized that karate-do, when seen as a well-rounded and highly challenging form of exercise and health maintenance, would greatly expand its public appeal and value.

Other qualities had to be learned before Funakoshi could become a successful pioneer. He gained a great sense of humility and modesty from Azato and Itosu. “If they taught me nothing else, I would have profited by the example they set of humility and modesty in all dealings with their fellow human beings.” These qualities were clearly evident when, struggling to make a living upon arrival in Japan, Funakoshi swept the floors and grounds of the Meisei Juku.

The quality of humility was fostered by his two primary instructors. As Funakoshi stated, “Both Azato and his good friend Itosu shared at least one quality of greatness: they suffered from no petty jealousy of other masters. They would present me to the teachers of their acquaintance, urging me to learn from each the technique at which he excelled.” All indications are that this demonstration of humility and respect made a life-long impression on young Funakoshi.

He learned valuable diplomacy skills as a young school teacher. As an example, he was asked to mediate a dispute involving two different factions by the village of Shaka. The issue was political and stemmed from Meiji reforms. Tact and intelligent arbitration was required to resolve a vexing situation. Also, his wife became known throughout their Okinawan neighborhood as a skillful mediator. When the neighbors grew quarrelsome, it was often Funakoshi’s wife who interceded on behalf of reason and peace. He had great respect for his wife and probably learned from her diplomatic qualities.

Because of his study with the other prominent karate masters of the day, his integrity and fairness, and his respected position as an educator, Funakoshi evolved into the primary Okinawan karate “public relations” spokesman. He represented a unique blend of well-rounded physical expertise, intelligence, foresight, and conviction. He was articulate, sensitive to tradition and propriety, appropriately humble, and conveyed a sense of balance. Funakoshi felt the pull of Japan and found a nation fertile with eagerness for a martial art with the depth of challenge that karate-do represented. This is surely part of the reason Funakoshi had difficulty ever leaving Japan to return to his family in Okinawa.

Summary

The Meiji Period represented a time of great social change in Japan and consequently Okinawa. With the covert aspect of karate practice no longer necessary, it was soon perceived that karate had much to offer to a rapidly changing society. Karate underwent a profound change — it evolved from merely a fighting art to an art which improves the character of its practitioners. This adaptation from a purely self-defense art to a method of self-improvement was probably a response to the social changes initiated by Meiji reforms.

Master Funakoshi described the new notion of karate in the following manner. “Karate is not only the acquisition of certain defensive skills, but also the mastering of the art of being a good and honest member of society.” This statement indicates the importance of self-improvement and contribution to a better society. No longer could “good” karate be defined simply as a fast punch or powerful kick. Qualities of character were also now a part of the equation. This concept is captured concisely by Funakoshi’s statement that “Karate begins and ends with courtesy.”

Funakoshi performed the task of primary spokesman for Okinawan karate with the capability of a seasoned diplomat. He expertly guided karate through a transition from a clandestine, provincial, feudal period, fighting system to a modern, widely-practiced member of the Japanese martial arts. His efforts and foresight provided the foundation for the wide appeal and eventual internationalization of modern karate.

The importance of Master Funakoshi’s accomplishments and contributions cannot be understated. Rather, events such as described below seem to poignantly capture Funakoshi’s sense of achievement.

“I still vividly recall every single moment of that day when I, with half a dozen of my students, performed karate kata in the imperial presence. The impoverished Okinawan youth who used to walk miles every night to his teacher’s house could hardly have foreseen, even in his dreams, such a high point in his karate career.”

At the end of his life, Funakoshi remembered this event as significant. Events such as this came to signify the emergence of karate as a traditional Japanese martial art. Events such as this also signify the pioneering role that Master Funakoshi so expertly performed.

Bibliography

- Funakoshi, G., Karate-Do Kyohan: The Master Text

- Funakoshi, G., Karate-Do: My Way of Life

- Haines, B., Karate: History and Tradition

- Mattson, G., The Way of Karate

- Musashi, M., A Book of Five Rings

- Nakayama, M., Dynamic Karate

- Nishiyama, H., Karate: The Art of Empty Hand Fighting

- Okazaki, T., Textbook of Modern Karate

- Random, M., The Martial Arts

- Rielly, R., The History of American Karate

- Turnbull, S., The Book of the Samurai

© 1992, Bruce D. Green, Japan Karate Association of Boulder,

4373 Apple Ct., Boulder, CO 80301 tel: 303/442-3289