History

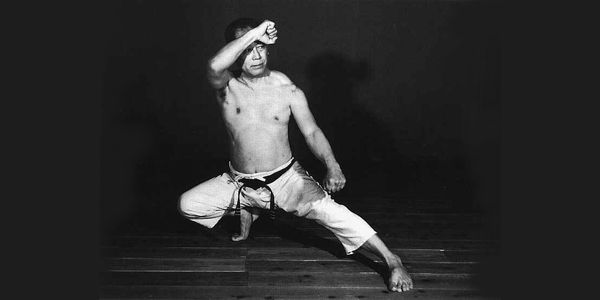

An elaborate code of movements of the arms and hands, and a flowing posturing of the body, “kata”, meaning form, model or structure, uses ritualistic movements to illustrate and record techniques of self-defense.

Although we know that the legacy of old style karate kata can be traced back to China and is an offspring of quanfa traditions, its birth and evolution evades modern researchers. We can speculate that kata took its form from cultural dances, dances which told stories of tribal history, current events, ancestors, heroes, harvests, hunting, war, victory, and religion -hence, an absolute expression of society, governed by historical and cultural considerations.

However, unlike dance, kata, in their relatively static positions and movements are of a utilitarian nature and have become regularized for efficiency and effectiveness, each possessing beauty in their brutal proficiency.

Kata are a cultural phenomenon of human movement acting as a catalog of individual “waza” (self-defense techniques), linked together into one seemingly simple pattern forming a specific reference work that preserves the art and bears the imprint of those who passed down the art to succeeding generations.

Old style karate traditions use kata as mnemonic aids, providing an explicatory outline for applying a set of logical “genron” (principles) and “heiho” (strategies) that can be tested and used in different situations. These principles are to be found in the waza or individual techniques positioned within the larger paradigm.

Waza

Waza is usually translated as technique but it literally means an act, a deed, work or performance and represents a prescribed series of defensive applications found within each tradition’s core curriculum and accumulated within the tradition’s kata.

The defensive applications of the individual waza represent more than blocking, kicking and punching – they comprise of joint manipulation (kansetsu waza), pinning/restraining techniques (katame waza), seizing nerves, attacking tendons, grappling (tuidi waza), attacking anatomically vulnerable points (kyushojutsu), strangulation and choking techniques (shime waza), sweeping and throwing techniques (nage waza), ground fighting techniques (ne waza) and countering attacks (gyaku waza).

Like all things in Japanese culture, karate integrates the principle of “in/yo” (dualism or complimentary opposites). This is often referred to as a “public face” and a “hidden face;” or in the martial arts “omote” and “ura”. In the context of waza, omote means the overt or obvious application of a waza that is readily apparent to the learner. In contrast ura indicates the implied or hidden components that aren’t immediately apparent to the learner. Through constant and repetitive practice of the omote level of waza, attention can thus be appropriately focused and time spent most productively in a beneficial study of the ura level in which alternate uses of the application will begin to reveal themselves.

Methods of Kata Study

The notion of learning and memorizing a vast array of waza or techniques which would accommodate each and every possible attack and variations thereof is impractical and does not constitute a true mastery of kata. On the contrary, old style karate traditions focused the learner’s attention on a few fundamental techniques to help the student understand the underlying logic and basic principles of a particular type of techniques, i.e. joint lock, throw, etc. Therefore, if one comes to understand the underlying principles of one technique of a particular type, that knowledge of the principles will transcend their understanding of other techniques of the same type and the need to memorize countless techniques is negated.

This method of focused study follows an educational process requiring several phases of learning a technique – namely; imitate, study and evaluate the movements of the technique using the pure execution of the waza without variation and internalize the underlying principles of the technique learned (“bunkai”); experiment to accommodate variations in speed, timing, distancing, attacks, entry into the technique, etc. and add to the understanding of the underlying principles (“henka”); and use the principles learned intuitively for the spontaneous application of technique (“oyo”). The three phases of learning kata have been simplified for illustrative purposes but as in all things in life it is much more complicated and should be better viewed as a continuum of these three phases with many reiterations.

This approach to learning has its roots in Japanese culture and relates to the concept of “Shu-Ha-Ri”. Shu-Ha-Ri literally means to; learn by tradition (Shu); break away from tradition (Ha); and transcend tradition (Ri). Shu-Ha-Ri corresponds to the transitions of life, including the phases of learning.

It should be noted that while Kata evolved as a way for the tradition to be preserved for future generations and as a mnemonic aid to be used when practicing alone, the primary mode of instruction of its individual waza was through partner training. Partner training creates a very alive and practical forum to connect “kihon waza” (foundational techniques) previously learned with the execution of the defensive technique. Learning of self-defense and the ability to apply the self-defense techniques rely on partner training.

Bunkai

The term bunkai meaning analysis; disassembly, suggests the breaking down and exploring of waza with an anticipated end result of executing the technique with correct body dynamics, strength and attitude, as well as learning the underlying principles upon which each waza functions. Given this definition, each waza becomes a sort of template, i.e. a reusable tool, used to gain a detailed and in-depth study of application principles through the analysis of a limited number of individual generic self-defense techniques found in kata.

It is important that we learn the waza of our tradition, but the training of waza must be much more than just empty performance and repetition. These waza become works-in-progress; and as we change both physically and in our understanding we come to consider them in new ways. Through the practice of waza we gain a practical understanding of balance, positioning, alignment, timing, distancing, openings, entries, speed, strength, breathing and power. We come to appreciate the varying methods in which one is attacked, our natural response to the attack and the reaction and effect of our technique on the attacker. In addition we begin to understand the basic logic and underlying principles that govern human movement and determine the execution of the technique, i.e. the natural laws of physics, principles of human anatomy and physiology, and the biomechanics of human motion including the generation and transfer of kinetic energy.

In the initial stages of bunkai, the learner lends their attention to the “showake” (details/intricacies) of individual movements. They focus on the details of balance, hip rotation, limb and hip alignment, power generation, muscle expansion and contraction, head and eye positioning, etc. and the basic defensive principle until the movements are remembered and the reflexes are sharpened. This is best done by repetitive practice in which a technique can be replicated and repetitively practiced as understanding is developed.

As one progresses in their study they begin to internalize the “youten” (main points) and “genron” (theory/underlying principles) observed during the execution of a technique. They use this understanding to research and experiment with the principles thereby extrapolating greater lessons for the broadening and deepening of the learner’s understanding of these underlying principles of technique.

Henka

Theoretically, the principles inherent in, and the direct applicability of, a given waza should be relevant to similar situations. However, the applicability is often times negated during a real-life attack due to the fact that a self-defense situation is dynamic in nature and always in a state of flux. The attacker may not enter into an attack in the same manner in which the waza has been taught and will do everything in their power to prevent you from executing the waza. Therefore, the waza must adapt to positional and situational circumstances to be utilized.

“Henka” meaning change; variation; alteration; transition, offers the learner the opportunity to explore differing scenarios in which to enter into and apply the waza and to continue to make the underlying principles understood and reflexive. The henka phase can be said to teach the major variations of these principles leading to a more advanced understanding.

Oyo

“Oyo” is translated as application, and refers to the practical use of the principles derived from a given waza which goes beyond that of the most simplistic interpretations. At this phase the learner can abandon (for the purpose of self-defense) the template we have been referring to as waza and apply the principles to a variety of situations. The template can be saved and re-used to teach another person.

Conclusion

Kata training usually begins with the practitioner being taught the fundamental techniques of karate (kihon waza) after which one learns one waza at a time. The waza is practiced with a partner where they strive for proper form and execution of the technique. Once the mechanics of the waza are mastered the learner begins to pick apart and analyze how and why the technique works. When the principles have been identified and understood, the learner begins to experiment using variables that could happen in a real situation. With methodical study and experimentation, the principles become ingrained in the learner and the principles can be applied to any situation. The relevance of the kata at this point becomes two-fold 1) it can be used to practice the techniques already learned when you are not able to work with a partner and 2) it can be saved and used as a template to aid the learning of another individual.