Many readers have written me in response to “The Link Between Martial Arts and Fitness,” and not all of you were complimentary. In particular, there were a lot of question about whether fitness means different things to a martial artist and an everyday Joe Schmoe. I’ve decided to elaborate on the subject here with this article Fitness for Martial Artists.

Fitness for the general public

Most Americans try to “get fit” in order to look good and to prevent the incidence of diseases that are a result of our lifestyle – sedentary jobs and processed, low-nutrient foods. For many, fitness is exemplified by tight, washboard abs, a shapely rear-end, and (if you’re a guy) nicely bulging muscles. Most others strive for low body fat, a low resting pulse rate, and the ability to bench press 300 or run for one hour straight. A more realistic group might try to emulate an athlete they admire in their own quest for fitness. They want the endurance and stamina of Lance Armstrong, the explosive speed of Michael Johnson, or the power of Jerome Bettis and Barry Bonds.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with any of these goals. It’s natural to want an attractive body, to have bodily statistics that make your physician smile happily at you, or to even come close to replicating the incredible accomplishments of the athletes I just mentioned.

But it’s not really related to function, is it? A popular catchphrase in the workout world these days is “functional fitness.” But let’s face it. The average American does not need a high level of fitness for their day-to-day survival. Many of us spend our days sitting at a desk, and even those of us who perform what might be considered “manual labor” for a living have it considerably easier than our grandparents did. It’s rare that we have to lift heavy things on a regular basis, we don’t have to walk or run very much, and even the average soldier can get away with not being all that fit, since modern warfare involves manipulating sophisticated weapons systems and not blood-and-guts hand-to-hand combat. Functional fitness for most of us means having the energy to stay awake during a boring afternoon meeting; being strong enough to carry our groceries into the house from the car or to play with our kids, and having our internal organs at a state where we don’t have to worry about them exploding at some inopportune moment and killing us.

But for a fighter and a martial artist, “functional fitness” is a problem that we’ve been (excuse the pun) grappling with for quite a while. And for us, being out of shape means not just losing a competition or a fight but getting hurt.

Fighting fit

A fighter needs to have the cardiovascular endurance of a long-distance runner, the speed and explosiveness of a sprinter, the strength of a powerlifter, and the staying power of an infantryman. A fighter also must have superior balance, flexibility, and agility – much like a dancer or a gymnast.

In fact, I would argue that true fighters or combat athletes – MMA fighters, boxers, and wrestlers – are the most highly conditioned people in the world today, unless you count members of military special forces (who, after all, are down-and-dirty blood-and-gut fighters at heart.) And why are these people so impossibly fit? Because they have to be.

How a fighter needs to train

The workout that the trainer at your health club recommends might help you achieve the general fitness goals discussed above. You’ll look good, lose weight, and maybe even gain some measure of success as a competitive athlete.

But it won’t work for a fighter. I know – I learned from experience.

One year, I entered a tournament, and in addition to all my skills training, I also went to the gym religiously. I regulated my diet; I ran and did all sorts of cardio on those nifty machines; I lifted weights on a regimen as prescribed by the gym’s trainer and based on what I had read in those men’s workout magazines that so proliferate our newsstands. And at tournament time, I looked good. I’m not being boastful: I had single-digit body fat, above-average upper-body strength for a guy in my weight class, and a visible six-pack. I could keep my pulse at the prescribed 80 percent of my theoretical max for 45 minutes with little difficulty.

I won my first match easily that year. But it drained me so much that for my second match, I could barely keep my hands up, much less put up a fight. Needless to say, I lost.

After I got over my disappointment, I tried to figure out where I had gone wrong. Perhaps I needed to devote more time to conditioning? But that was ridiculous; I might not have been training full time, but I was putting in 10 hours a week at the gym, in addition to my skills training. By all general standards, I was an extremely fit guy.

But I wasn’t fit the way a fighter should be. The problem wasn’t how much time I was training – in my research on how boxers train, I discovered that they don’t put in significantly longer hours in physical conditioning. But they train smarter, and with the goal of becoming “fighting fit” – not just fit as the public thinks of the term.

I’ve spent the past few years experimenting and researching to see how they do it. I’m not convinced I’ve found the most efficient way yet, but what I do now is immeasurably better than the workouts you’ll read in most so-called “fitness” magazines and what you’ll get from a health club trainer. I can outlast a lot of my training partners when I go to class; many of them will remark that I’m “stronger than I look” or have amazing staying power. The only people who can beat me are those who are good enough to overwhelm me quickly; otherwise, I just wear them out. (Alas, I freely admit that there are still quite a few guys in the schools where I train that are good enough to do so. But they’re friends, and they inspire me to improve my technique.)

The best part of my new methods is, my body feels remarkably pain free; I have very few of the aches and pains that most athletes suffer from. Also, I can work out at home, since I need very little equipment to work every aspect of my game – during storage, all my equipment takes up less than two square feet. In fact, the only reason I still belong to a health club is because I enjoy swimming occasionally – for recreation – and because it’s nice to have access to a steam room and sauna during the wintertime.

I suppose I should tell my fellow students about my smarter training methods, but I like being able to grind them to the ground during training. Hopefully, some of them will read this and figure out my secrets – which aren’t really secrets at all. They’re just not that well publicized.

What I’ve found to be effective

I generally work out three times a week for 40 minutes – that includes cool down time. If I have time on the weekend, I’ll throw in a fourth “workout” that involves something like a jog or a swim – but that’s more for recreation than anything else. That’s one fifth the time I used to need.

There are two basic regimens that I follow, and I generally switch off, doing one exclusively or combining elements from both.

Kettlebells

Kettlebells were once quite popular all over the world, including in Europe and the United States, but had all but disappeared from the Western world for the past 60 years or so. But the Soviets continued to use them, and it is a former Soviet special forces (Spetsnaz) fitness trainer, Pavel Tsatsouline, who re-introduced them to Americans after the Berlin Wall came down. According to an article in the Christian Science Monitor, they’re currently used by many U.S. elite units, who discovered them when they found (in friendly post-Cold War joint training exercises and drills) that their Russian counterparts were so much more fit that tasks that had our boys dropping from exhaustion barely made the Russians break a sweat. The secret was kettlebells.

Embarrassingly enough, for all the expensive equipment U.S. companies have developed that supposedly help us get fit – Nautilus machines, elliptical trainers, stairmasters, etc. – it’s a centuries-old Russian-designed hunk of cast iron that really does the job. Kettlebells are basically moderately heavy cannonballs with thick handles on them. They range in weight from 36 pounds (new lighter versions for women have recently been introduced) to 88 pounds.

I won’t go into how to use a kettlebell in this article; that subject is discussed at length and very well at https://www.dragondoor.com and at https://www.cbass.com/Kettlebell.htm.

Here are the advantages of using a kettlebell:

- Kettlebells are very, very effective. They build whole-body strength, and especially develop the legs, back, and core muscles very well. You learn how to use these muscles in conjunction, which is a major requirement for every fighter and athlete.

- What’s more, you get stronger without adding heavy muscle mass, which can slow you down and make you look like a steroid freak.

- I’ve also found that using kettlebells increases practical endurance by leaps and bounds. I’m not talking about the ability to run marathon — who needs to do that in the real world? — but the ability to keep fighting for long periods of time. (More distastefully, using kettlebells also means you can help your buddies move furniture for a much longer time without collapsing.)

- And for fighters trying to drop weight, kettlebells ramp up your metabolism very quickly. When I first used kettlebells, I found myself constantly ravenous, and it was an effort to keep my portions the same as they were before.

- Kettlebells are far cheaper than a gym membership. Two kettlebells, an instructional DVD, a kettlebell book, and shipping will run about $250. That sounds like a lot, but in New York City, that sum barely covers six months of gym fees. Those kettlebells will last your forever.

But, alas, there are also disadvantages to using kettlebells:

- It takes careful training before you can use a kettlebell confidently. You’re basically heaving a large heavy chunk of iron around, and if you use improper form, you can very easily lose control of it. That means you might drop or hurl it accidentally on your head, your feet, your TV, your priceless Ming vase, etc. You get the idea.

- While kettlebell training is very efficient — you can get huge results in minimal training time — it also hurts like hell. When begin using them, painful blisters will develop on your palms and bruises will appear on your forearms. And if you’re pushing yourself as you should be, you’ll collapse in a painful heap after every workout, and sometimes throw up. (But don’t worry, an hour later you’ll feel great.)

- Kettlebells don’t travel well. That means that if you’re on the road a lot or want to stay in shape on vacation, you’re going to want to find another alternative.

Combat Conditioning

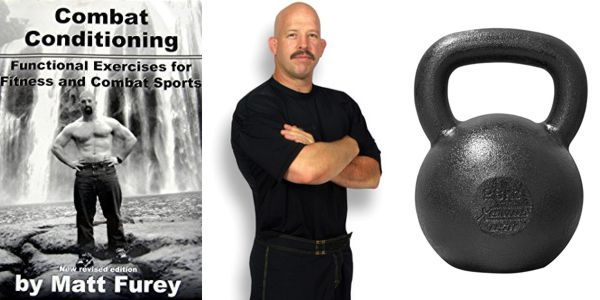

The second method I found doesn’t bring results as quickly as kettlebells do, but it is still very good. It also offers some advantages that kettlebells don’t. It’s a system of bodyweight exercises called Combat Conditioning. The name was coined by Matt Furey, a noted wrestler and shuai chiao fighter who learned them from an old-time pro wrestler. (And by pro wrestler, I don’t mean an entertainer who performs staged “fights” such as Hulk Hogan or the Rock. I mean an old timer who wrestled for real when wrestling was a real, legal sporting event. [Editor’s note: By law, all U.S. wrestling matches must be staged and have a pre-determined victor. Real, non-Olympic and non-collegiate wrestling was deemed too brutal early in the 20th century.]) Ultimately, the core of the exercises in Furey’s Combat Conditioning come from the training done by the legendary wrestlers of India such as Ghulum Mohammed, aka the Great Gama. They include specialized bodyweight squats and pushups and a wrestler’s back bridge. You can find more about this regimen at www.mattfurey.com/combat-conditioning.

Although kettlebells yield spectacular results, I always go back to Combat Conditioning because it offers many benefits as well.

- CC relieves joint pain like nobody’s business. Like many active but aging people, I experience various types of knee pain whenever I’ve been overdoing the running or the mat work. But instead of resting and icing it (and letting my conditioning slip) as most doctors tell you, I return to Combat Conditioning, and the knee pain goes away. The exercises are also great for preventing shoulder injuries and improving one’s posture.

- Secondly, Combat Conditioning is a great way to stay in shape while traveling. None of the exercises require anything more than your own body and perhaps a sturdy chair; this means you don’t have to depend on musty, rusty, crappy hotel gyms to stay in shape.

- CC also helps develop superior body awareness, which is especially helpful for grapplers. This body awareness also makes my body feel really good — unified, powerful, light, and indestructible. There are just a few disadvantages to CC.

- CC is as effective at burning fat as other methods, such as kettlebells or just plain running.

- Because CC involves working with only your bodyweight, it is difficult to get significantly stronger in a short period of time.