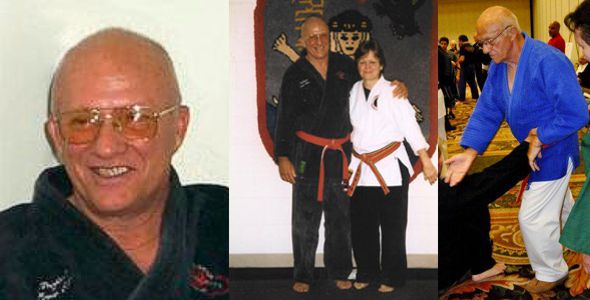

Professor Ernie Cates has been tossing other people’s weight around for more than five decades. At age 14 he began jujitsu training then in 1954 as a Marine, Cates continued his jujitsu training in Japan, Korea and while stationed in Okinawa he began studying judo under Matsumoto Sensei.

“In 1956 I was a member of the 5 man U.S. Armed Forces Team that succeeded in winning the Ryukyu Islands Championship that has always been held by the Japanese police teams,” Cates recalled proudly. “After that I trained in Japan at the Kodokan.”

Among Ernie Cates many accomplishments in the sport of judo includes his seven consecutive years as the winner of the All Marine Corp Judo Championships in his weight group. Concurrently, he went on to win Grand Champion defeating all other weight group winners for five years in a row, in addition to twice winning the Inner Service Championships. In 1963 he won the Southern United States, AAU Grand Championship.

Professor Ernie Cates has taken a lifetime worth of discipline and knowledge and created his own style called, Neko Ryu Jujitsu. “Neko means cat in Japanese and is based upon the natural movements and alignment of the body much as a cat moves,” Cates says. “A cat moves without effort; by aligning its body it has tremendous agility and power. A cat can jump approximately seven times its height at its shoulders from a sitting position. It can also carry three times its body weight in its mouth while climbing up a tree. Cats don’t get in shape by doing push-ups and pull ups; a cats strong because it stretches properly and utilizes its natural inner strength.”

Taking a cue from the agile feline, Cates uses ki to energize the flow of the body’s energy to align the muscles properly which produces the tremendous strength necessary to accomplish the movement. Although working from a strong jujitsu and judo foundation Cates explains that his style of Neko Ryu is best compared to the early combative style of Aikido as practiced by Tomiki and Tohei Senseis.

“Aikido is a beautiful art but even the staunchest practitioner of aikido will tell you that it takes years of practice before you can take an unwilling opponent to the ground and subdue him using the graceful flowing movements that blend attacker and defender into one.” Cates said. “We teach the same principles in Neko Ryu but we use short cuts and all of our techniques have a completion. What might require four or five aikido movements we have modified to a single continuous movement.”

Demonstrating one of his short cuts Professor Cates refers to a technique against a grab. In Aikido they will use a double tai sabaki (turning twice) to put a person down. Instead, we just enter into the opponents centerline, bring the arm up in an arc under their chin and take them down,” Cates explained. “If I have a businessman or soldier that wants to learn a system of self defense in a 4-hour short course of intense instruction, he can walk out the door and be assured that he can effectively defend himself against an untrained attacker.”

The differences between an Aikido technique and Nekyo Ryu technique are as subtle as a change of body positioning. His “short cuts” are a direct result of years of training which he has evolved into a system that embraces the best of what he has learned while discarding the superfluous.

“Many of our techniques are based upon judo and jujitsu principles,” Cates said. “Take O-soto-gari (major outer reaping throw) for example; we teach the detail of using the toe pointed down instead of up. This enables you to sweep your opponent’s leg with an upward arcing motion rather than driving the heel into the back of the opponent’s lower leg.”

In judo, players usually push, pull or tug on their adversaries’ gi to break his or her balance to set up a throw. In Nekyo Ryu none of these traditional maneuvers are used to achieve kuzushi (body control).

“We maximize the understanding of balance and kuzushi. Kuzushi is a matter of off-balancing, “Cates explained. “Instead of pushing or pulling, you relax and use your entire body as you come in for the throw. Thus, you move your entire body weight as a single unit. In the case of osoto gari the leg becomes a natural part of that movement as you go past your opponent. It’s as if you were walking past them and by aligning your body with theirs, it will cause a shift in their weight and balance that will cause them to tip, and if you tip a balanced pole at the top a half inch it will fall over by itself, and that’s what happens to a person during the movement of kuzushi.”

After years of traditional training that encompassed falling, punching, kicking, and joint locking techniques Cates has endured his share of injuries that include multiple surgeries on his shoulders, knees, and elbows. He claims that if he knew back in 1955 what he knows now none of those surgeries would have been necessary.

“I am constantly running into individuals that tell me, ‘I can’t do this because of an injury.” Cates said. “After watching different martial arts disciplines it was clear to me one glaring difficulty was the lack of proper warm up, which over time is what creates serious injuries. If I had known how to warm-up properly I would never have endured so many injuries.”

Professor Ernie Cates went on to say that he’d watch people do sit-ups, push-ups, jumping jacks, and kicking and punching drills, all of which may break a strong sweat and strengthen the muscles, however, not accomplish proper stretching and loosen the entire body.

“Too many instructors confuse quality with quantity by making the warm-up process ridiculously hard.” proclaimed Cates. I have witnessed instructors boasting about how “tough” their warm ups were which just leads to students who are tired, muscularly fatigued and mentally exhausted. It is at this point that students are prone to serious injury.” Warm ups done improperly tighten the muscles rather than increase flexibility, muscular control and preparation for a concentrated workout.”

“The karate classes would snap a kick straight out and bring it back without realizing that each one of those power kicks to the air without any resistance is slightly separating the knee. Granted, a very small separation, but multiply that over a period of years of kicking several hundred times a class will eventually produce a knee problem. Same thing with their punches, each one is extending the elbow and over extending the shoulder. Martial artists, after following this traumatic warm-up routine will little-by-little turn themselves into cripples.”

Ernie Cates said that the same kind of injuries occur in judo during uchi koma (repetitive movements for a throw) drills where students repetitively drive fast and hard into their opponent attempting to jack them up into the air. According to Cates this creates two problems, first they’re cold and not warmed up properly thus setting themselves up for an injury, and secondly, if they possess a faulty habit, every time they drive into their partner at full speed they reinforce the faulty habit. And when that happens, two people get hurt; the person doing the throw and the person being thrown.

Professor Cates insists that his method of doing warm-ups will increase a martial artist’s longevity by allowing them to train well into their senior years, thus he jokingly refers to his techniques as geriatric judo. Also, by warming up in this manner, the martial artist can practice his techniques correctly and build good skills.

“I call my warm-up technique Snake and Blanket,” said Cates. “It is actually mat work done at half speed and one-quarter strength, no power is exerted. You start out back-to-back then begin grappling movements without using any power.”

The person on top is the blanket, always trying to cover the person on the bottom who is attempting to “snake” his or her way out and into the blanket position. The key to doing this is not to be overly competitive. By maintaining a slow but steady series of movements both the snake and the blanket get a thorough warm up without putting any stress on their joints or muscles while increasing flexibility.

“By using grappling movements you will utilize every muscle that you would use if swimming,” said Cates. “You will slowly stretch the tendons, ligaments and your muscles. In doing this you increase your heart rate and also learn that pinning the individual, arm baring them or choking techniques isn’t a matter of power, it’s a matter of principle, body placement and movement.” “If you master the principle, the technique happens.”

Professor Cates teaches according to the motto put forth by judo’s founding father Jigoro Kano when he said of his sport “Judo is maximum efficiency with minimum effort.”

“Today most martial artists are doing just the opposite,” said Cates. “They’re practicing with maximum effort and ending up with minimum efficiency. So we have put together a form of warming up and a form of doing uchi komi whereby you don’t slam into each other, instead you come into the technique slowly allowing you to concentrate on the proper angle of the throw, to perform and understand the entire principle and in doing so enhance your ability and skills.”

Another skill Ernie Cates has perfected over the years is Shime-waza (choking techniques.) He freely admits that for decades he’d been working under a misconception when it came to the medical science behind the choke.

“Choking techniques are misunderstood in all of the martial arts,” said Cates. In 1990, while giving a lecture in Florida, on strangulation technique I talked about cutting off the blood supply to the brain by collapsing the carotid artery. Following the lecture I was approached by a well known heart surgeon who corrected me. He explained that the choke was not a blood-strangle but rather a nervous reaction to a danger signal that is sent to the brain.”

The heart surgeon went on to say that the carotid artery is well protected, by a carotid sinus which surrounds it and that sinus is a barrel receptor. When pressure is put upon the carotid sinus the nerves send a message up to the brain saying that the artery is about to be cut off so the brain automatically protects itself.

“The brain protects itself the same way a very sensitive individual would if you told that person his mother just died and he passes out,” Cates explained.

Ernie Cates insists that chokes should be applied as if imitating a silken cord. “Applying a choke with power defeats the purpose of a choke,” says Cates. “You don’t want to choke someone as if you were using a piece of lumber. The forearms and hands are relaxed so uniform pressure can be applied to the vital areas, subsequently putting pressure on the nerves that make the individual pass out.”

In addition to “soft hands” the person doing the choke must have full body control of his or her opponent for the technique to be effective. According to Professor Cates complete control is imperative for a choke to work.

“During ground work for example, if a person is in the top mounted position applying a cross lapel choke and leans forward the choke will work, however if the person on the bottom simply hooks the opponent’s foot, leg or hip, controlling a part of his body he will not able to make an effective choke. It’s very subtle but he can’t apply the choke because he cannot align his body properly.”

“The ultimate goal of a martial arts instructor is to provide for their students longevity in their disciplines. To approach teaching and proper training using the mind, body and spirit, thereby developing character and integrity.”