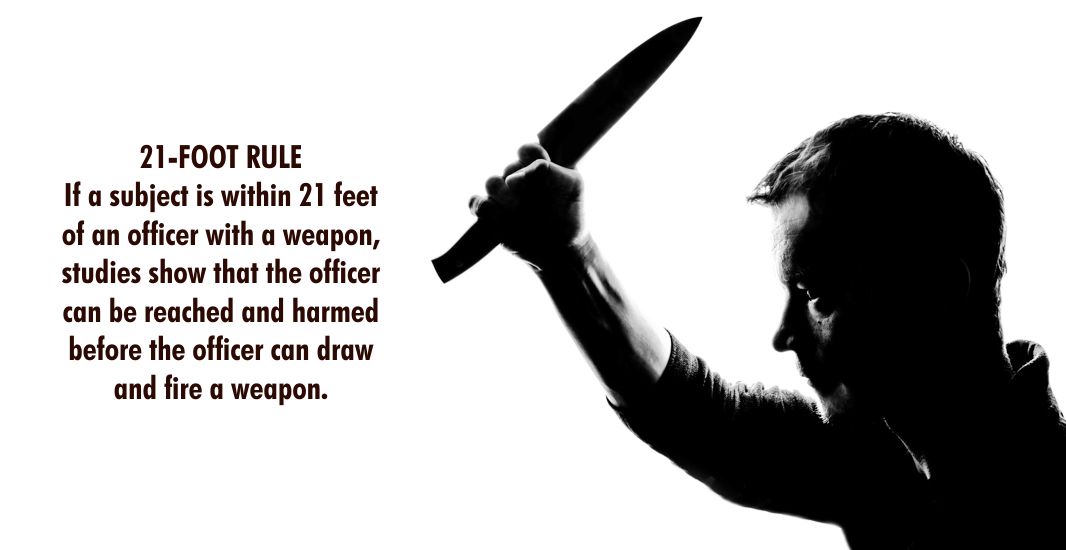

PoliceOne.com Editors Note: For the record, the 21-Foot Rule, when accurately stated, says that in the time it takes the average officer to recognize a threat, draw his sidearm and fire 2 rounds at center mass, an average subject charging at the officer with an edged weapon can cover a distance of 21 feet. Thus, when dealing with an edged-weapon wielder at anything less than 21 feet you need to have your gun out and ready to shoot before he starts rushing you or else you risk being set upon and injured or killed before you can draw your sidearm and effectively defeat the attack.

For more than 20 years now, a concept called the 21-Foot Rule has been a core component in training officers to defend themselves against edged weapons.

Originating from research by Salt Lake City trainer Dennis Tueller “rule” states that in the time it takes the average officer to recognize a threat, draw his sidearm and fire 2 rounds at center mass, an average subject charging at the officer with a knife or other cutting or stabbing weapon can cover a distance of 21 feet.

The implication, therefore, is that when dealing with an edged-weapon wielder at anything less than 21 feet an officer had better have his gun out and ready to shoot before the offender starts rushing him or else he risks being set upon and injured or killed before he can draw his sidearm and effectively defeat the attack.

Recently a Force Science News member, a deputy sheriff from Texas, suggested that it’s time for a fresh look at the underlying principles of edged-weapon defense, to see if they are “upheld by fresh research.” He observed that “the knife culture is growing, not shrinking,” with many people, including the homeless, “carrying significant blades on the street.” He noted that compared to scientific findings, “anecdotal evidence is not good enough when an officer is in court defending against a wrongful death claim because he felt he had to shoot some[body] with a knife at 0-dark:30 a.m.”

As a prelude to more extensive studies of edged-weapon-related issues, the Force Science Research Center at Minnesota State University-Mankato has responded by reexamining the 21-Foot Rule, arguably the most widely taught and commonly remembered element of edged-weapon defense.

After testing the Rule against FSRC”s landmark findings on action-reaction times and conferring with selected members of its National and Technical Advisory Boards, the Center has reached these conclusions, according to Executive Director Dr. Bill Lewinski:

- Because of a prevalent misinterpretation, the 21-Foot Rule has been dangerously corrupted.

- When properly understood, the 21-Foot Rule is still valid in certain limited circumstances.

- For many officers and situations, a 21-foot reactionary gap is not sufficient.

- The weapon that officers often think they can depend on to defeat knife attacks can’t be relied upon to protect them in many cases.

- Training in edged-weapon defense should by no means be abandoned.

In this installment of our 2-part series, we’ll examine the first two points.

1. MISINTERPRETATION

“Unfortunately, some officers and apparently some trainers as well have ”streamlined” the 21-Foot Rule in a way that gravely distorts its meaning and exposes them to highly undesirable legal consequences,” Lewinski says. Namely, they have come to believe that the Rule means that a subject brandishing an edged weapon when positioned at any distance less than 21 feet from an officer can justifiably be shot.

For example, an article on the 21-Foot Rule in a highly respected LE magazine states in its opening sentence that “a suspect armed with an edged weapon and within twenty-one feet of a police officer presents a deadly threat.” The “common knowledge” that “deadly force against him is justified” has long been “accepted in police and court circles,” the article continues.

Statements like that, Lewinski says, “have led officers to believe that no matter what position they’re in, even with their gun on target and their finger on the trigger, they are in extreme danger at 21 feet. They believe they don’t have a chance of surviving unless they preempt the suspect by shooting.

However widespread that contaminated interpretation may be, it is NOT accurate. A suspect with a knife within 21 feet of an officer is POTENTIALLY a deadly threat. He does warrant getting your gun out and ready. But he cannot be considered an actual threat justifying deadly force until he takes the first overt action in furtherance of intention–like starting to rush or lunge toward the officer with intent to do harm. Even then there may be factors besides distance that influence a force decision.

So long as a subject is stationary or moving around but not advancing or giving any indication he’s about to charge, it clearly is not legally justified to use lethal force against him. Officers who do shoot in those circumstances may find themselves subject to disciplinary action, civil suits or even criminal charges.

Lewinski believes the misconception of the 21-Foot Rule has become so common that some academies and in-service training programs now are reluctant to include the Rule as part of their edged-weapon defense instruction for fear of non-righteous shootings resulting.

When you talk about the 21-Foot Rule, you have to understand what it really means when fully articulated correctly in order to judge its value as a law enforcement concept,” Lewinski says. “And it does not mean ”less than 21 feet automatically equals shoot.

2. VALIDITY

In real-world encounters, many variables affect time, which is the key component of the 21-Foot Rule. What is the training skill and stress level of the officer? How fast and agile is he? How alert is he to preliminary cues to aggressive movement? How agile and fast is the suspect? Is he drunk and stumbling, or a young guy in a ninja outfit ready to rock and roll? How adept is the officer at drawing his holstered weapon? What kind of holster does he have? What’s the terrain? If it’s outdoors, is the ground bumpy or pocked with holes? Is the suspect running on concrete, or on grass, or through snow and across ice? Is the officer uphill and the suspect downhill, or vice versa? If it’s indoors, is the officer at the foot of stairs and the suspect above him, or vice versa? Are there obstacles between them? And so on.

These factors and others can impact the validity of the 21-Foot Rule because they affect an attacking suspect’s speed in reaching the officer, and the officer’s speed in reacting to the threatening charge.

The 21-Foot Rule was formulated by timing subjects beginning their headlong run from a dead stop on a flat surface offering good traction and officers standing stationary on the same plane, sidearm holstered and snapped in. The FSRC has extensively measured action and reaction times under these same conditions. Among other things, the Center has documented the time it takes officers to make 20 different actions that are common in deadly force encounters.

Here are some of the relevant findings that the FSRC applied in reevaluating the 21-Foot Rule:

- Once he perceives a signal to do so, the AVERAGE officer requires 1.5 seconds to draw from a snapped Level II holster and fire one unsighted round at center mass. Add 1/4 of a second for firing a second round, and another 1/10 of a second for obtaining a flash sight picture for the average officer.

- The fastest officer tested required 1.31 seconds to draw from a Level II holster and get off his first unsighted round. The slowest officer tested required 2.25 seconds.

- For the average officer to draw and fire an unsighted round from a snapped Level III holster, which is becoming increasingly popular in LE because of its extra security features, takes 1.7 seconds.

- Meanwhile, the AVERAGE suspect with an edged weapon raised in the traditional “ice-pick” position can go from a dead stop to level, unobstructed surface offering good traction in 1.5-1.7 seconds.

- The “fastest, most skillful, most powerful” subject FSRC tested “easily” covered that distance in 1.27 seconds. Intense rage, high agitation and/or the influence of stimulants may even shorten that time, Lewinski observes.

- Even the slowest subject “lumbered” through this distance in just 2.5 seconds.

Bottom line: Within a 21-foot perimeter, most officers dealing with most edged-weapon suspects are at a decided – perhaps fatal – disadvantage if the suspect launches a sudden charge intent on harming them. “Certainly it is not safe to have your gun in your holster at this distance,” Lewinski says, and firing in hopes of stopping an activated attack within this range may well be justified.

But many unpredictable variables that are inevitable in the field prevent a precise, all-encompassing truism from being fashioned from controlled “laboratory” research.

“If you shoot an edged-weapon offender before he is actually on you or at least within reaching distance, you need to anticipate being challenged on your decision by people both in and out of law enforcement who do not understand the sobering facts of action and reaction times,” says FSRC National Advisory Board member Bill Everett, an attorney, use-of-force trainer and former cop. “Someone is bound to say, ”Hey, this guy was 10 feet away when he dropped and died. Why did you have to shoot him when he was so far away from you?””

Be able to articulate why you felt yourself or other innocent party to be in imminent or immediate life-threatening jeopardy and why the threat would have been substantially accentuated if you had delayed, Everett advises. You need to specifically mention the first motion that indicated the subject was about to attack and was beyond your ability to influence verbally.

And remember: No single rule can arbitrarily be used to determine when a particular level of force is lawful. The 21-Foot Rule has value as a rough guideline, illustrating the reactionary curve, but it is by no means an absolute.

The Supreme Court’s landmark use-of-force decision, in Graham v. Connor, established a ”reasonableness standard,” Everett reminds. You’ll be judged ultimately according to what a reasonable officer would have done. All of the facts and circumstances that make up the dynamics between you and the subject will be evaluated.”

Of course, some important facts may be subtle and now widely known or understood. That’s where FSRC”s unique findings on lethal-force dynamics fit in. Explains Lewinski: “The FSRC”s research will add to your ability to articulate and explain the facts and circumstances and how they influenced your decision to use force.”

3. MORE DISTANCE

In reality, the 21-Foot Rule–by itself–may not provide officers with an adequate margin of protection, says Dr. Bill Lewinski, FSRC’s executive director. “It’s easily possible for suspects in some circumstances to launch a successful fatal attack from a distance greater than 21 feet.

Among other police instructors, John Delgado, retired training officer for the Miami-Dade (FL) PD, has extended the 21-Foot Rule to 30 feet. “Twenty-one feet doesn’t really give many officers time to get their gun out and fire accurately,” he says. Higher-security holsters complicate the situation, for one thing. Some manufacturers recommend 3,000 pulls to develop proficiency with a holster. Most cops don’t do that, so it takes them longer to get their gun out than what’s ideal.

Also shooting proficiency tends to deteriorate under stress. Their initial rounds may not even hit. Beyond that, there’s the well-established fact that a suspect often can keep going from momentum, adrenalin, chemicals and sheer determination, even after being shot. Experience informs us that people who are shot with a handgun do not fall down instantly nor does the energy of a handgun round stop their forward movement, states Chris Lawrence, team leader of DT training at the Ontario (Canada) Police College and an FSRC Technical Advisory Board member.

Says Lewinski: “Certain arterial or spinal hits may drop an attacker instantly. But otherwise a wounded but committed suspect may have the capacity to continue on to the officer’s location and complete his deadly intentions.” That’s one reason why tactical distractions, which we’ll discuss in a moment, should play an important role in defeating an edged-weapon attack, even when you are able to shoot to defend yourself.

When working with bare-minimum margins, any delay in an officer responding to a deadly threat can equate to injury or death, reinforces attorney and use-of-force trainer Bill Everett, an FSRC National Advisory Board member. So the officer must key his or her reaction to the first overt act indicating that a lethal attack is coming.

More distance and time give the officer not only more tactical options but also more opportunity to confirm the attacker’s lethal intention before selecting a deadly force response.

4. MISPLACED CONFIDENCE

Relying on OC or a Taser for defeating a charging suspect is probably a serious mistake. Gary Klugiewicz, a leading edged-weapon instructor and a member of FSRC’s National Advisory Board, points out that firing out Taser barbs may be an effective option in dealing with a threatening but STATIONARY subject. But depending on this force choice to stop a charging suspect could be disastrous.

With fast, on-rushing movement, there’s a real chance of not hitting the subject effectively and of not having sufficient time” for the electrical charge–or for a blast of OC–to take effect before he is on you, Klugiewicz says.

Lewinski agrees, adding: A rapid charge at an officer is a common characteristic of someone high on chemicals or severely emotionally disturbed. More research is needed, but it appears that when a Taser isn’t effective it is most often with these types of suspects.

Smug remarks about offenders foolishly “bringing a knife to a gunfight” betray dangerous thinking about the ultimate force option, too. Some officers are cockily confident they’ll defeat any sharp-edged threat because they carry a superior weapon: their service sidearm. This belief may be subtly reinforced by fixating on distances of 21 or 30 feet, as if this is the typical reaction space you’ll have in an edged-weapon encounter.

The truth is that where edged-weapon attacks are concerned, close-up confrontations are actually the norm,” points out Sgt. Craig Stapp, a firearms trainer with the Tempe (AZ) P.D. and a member of FSRC’s Technical Advisory Board. A suspect who knows how to effectively deploy a knife can be extremely dangerous in these circumstances. Even those who are not highly trained can be deadly, given the close proximity of the contact, the injury knives are capable of, and the time it takes officers to process and react to an assault.

At close distances, standing still and drawing are usually not the best tactics to employ and may not even be possible. At a distance of 10 feet, a subject is less than half a second away from making the first cut on an officer, Lewinski’s research shows. Therefore, rather than relying on a holstered gun, officers must be trained in hands-on techniques to deflect or delay the use of the knife, to control it and/or to remove it from the attacker’s grasp, or to buy time to get their gun out. These methods have to be simple enough to be learned by the average officer.

Stapp strongly believes that training in edged-weapon defense should prepare an officer to deal psychologically with getting cut or stabbed, a realistic probability with lag time, close encounters and desperate control attempts. Officers need to be trained to continue to fight, Stapp says. They will not have time to stop and assess how severe the wound is. You don’t want them in the mind-set, ‘I’ve been cut, I’m going to die.’ They must remain focused on stopping the attack, taking out the guy who is the threat to them.”

Checking yourself over for injury after the offender is subdued is important, too, Klugiewicz says. “Some survivors of edged-weapon attacks report that they were not aware of being cut or stabbed when the injury occurred. They thought they had just been punched and didn’t realize what really happened until later.”

5. TRAINING

Assuming it is presented accurately and in context with the many variables that shape knife encounters, the 21-Foot Rule can be a valuable training aid, Lewinski says. As a role-playing exercise, it provides a dramatic and memorable demonstration of how fast an offender can close distance, and it can motivate officers to improve their performance skills. Experiment with it and you may conclude, like Delgado, that 21 feet is not enough of a safety margin for your troops.

You might also use 21-Foot Rule exercises to test tactical methods for imposing lag time on offenders in order to buy more reaction time for officers. These could range from using or creating obstacles (standing behind a tree or shoving a chair between you and the offender) to moving yourself strategically. You’re probably familiar with the Tactical L, for example, in which an officer moves laterally to a charging offender’s line of attack. With the right timing, this surprises and slows the attacker as he processes the movement and scrambles to redirect his assault, and gives the officer opportunity to draw and get on target.

Lewinski favors a variation called the Tactical J. Here, instead of moving 90 degrees off line, the officer moves obliquely forward at a 45-degree angle to the oncoming offender. This tends to be more confusing to the suspect and requires more of a radical change on his part to come after you, Lewinski says. But the timing has to be such that the suspect is fully committed to his charge and can’t readily adjust to what you’ve done. That takes lots of practice with a wide variety of training partners.

If nothing else, training with the 21-Foot Rule will help officers better estimate just how far 21 feet is. Without a good deal of practice, most can’t accurately gauge that distance, Lewinski says, and thus tend to sabotage appropriate defensive reactions.

Don’t forget, though, that most edged-weapon attacks are up close and personal.

That means training must include effective empty-hand-control techniques, close quarters shooting drills and weapon retention. We need to develop the ability to draw our sidearm, get on target and GET HITS extremely fast, while moving as a diversionary measure if possible, says Stapp. Close-range shooting–under 10 feet–will most effectively be accomplished when an officer has developed the ability to get on target ‘by feel,’ without using his sights.

Lewinski also recommends drills to imprint rapid reholstering techniques. Reholstering may become necessary if there’s a sudden change in threat level–say the offender throws his weapon down and is no longer presenting an imminent threat justifying deadly force–and the officer needs both hands free to deal with him.

There’s little doubt that the knife culture and related attacks on officers are dangerously flourishing. Edged-weapon assaults are a staple of the news reports of police incidents from across the U.S. and Canada on the website of FSRC’s strategic partner, PoliceOne.com. Recently an officer in New York City was slashed in the face during a fight that broke out. On a man-with-a-gun call, in Ohio, a state trooper fatally shot a berserk motorist who charged him with a hatchet. And another offender, who called 911 in Pennsylvania to report he was having a heart attack, ended up shot 13 times and killed after commands and OC failed to stop him from lunging at a trooper with a chain saw. In Calgary (Canada) a blood-soaked man waved a bloody butcher knife over his head and charged at constables who responded to a domestic dispute. A suspected rapist attacked a Chicago detective with a screwdriver after luring him into an interrogation room by asking for a cigarette. In the reception area of a California prison, an inmate serving time for trying to kill a cop stabbed a correctional officer to death with a shank. In Idaho, an out-of-control teenager punched holes in the walls of his house with a 15-inch bayonet, then turned on a responding officer with the blade and sliced his uniform before the cop shot him.

Given today’s environment, rather than draw back on edged-weapon training, officers and agencies should be expanding it, Lewinski declares. Edged-weapon attacks are serious and should be taken seriously by trainers, officers and administrators alike. Finding out what works best in the way of realistic tactical defenses and then training those tactics as broadly as possible has never been more needed.

From www.forcescience.org