As I began preparing my thoughts for this article I struggled with the best way to title it. The word recalcitrant can describe a student in different. Clearly when we teach younger children they can be disobedient and fail to pay attention. However the focus of this article is not on the younger students, but those who are teenagers to adults. I would also like to state at the beginning not all students meet the focus of this article.

Over the past couple of days I’ve been involved in discussions with fellow martial artists about a variety of subjects. One of my senior AKS black belts recounted a situation he had had with some former students whose reaction to a black belt level testing didn’t meet with their idea of what should have been appropriate. It reminded me of situations I’ve encountered in years gone by with students who felt they were smarter and more experienced than their teacher. They failed to understand the importance of patience in developing one’s skills and knowledge. Key among these skills is control.

My senior student, Dr. Rob Debelak, pointed out a cultural aspect to the discussion involving a lack of respect on the part of today’s students, coupled with a “me first” attitude. He reminded me of the patience and discipline we were required to have when we first started our training. He also provided a couple of examples: Think back to the 1970’s movie Kung Fu where the student stood outside the training hall for days on end waiting to be invited in to learn. At one point the boy was invited in along with several others and provided food. The other boys eat at once, while the younger did not. The other boys were excused, but the younger boy was kept behind. When the teacher asked him why he hadn’t eaten the boy replied it wouldn’t have been proper to do so until the teacher had first been served and gave them permission to start.

The contemporary dilemma, (my AKS black belt with the family who didn’t feel the training was realistic enough) brings to light this lack of respect. It seems one member of the family in my black belts class, having read a particular author’s view about realistic training, didn’t feel the test challenged the knowledge and skill level of those being reviewed for promotion. They felt the parties were already aware of what was to take place (e.g. they had rehearsed their movements and responses). Their Sensei explained the necessity for those preparing to test for a specific rank must work with the person or persons who would be assisting them during the test. This would result in less chance of injury to either party during the test when their adrenalin would be at its peak.

It appears the interpretation of this author who had had such an influence on this student (and family) espoused a philosophy of not holding back during training in order to ensure the training was as realistic as possible. The student, seeing the merit of this felt the way she and her family were being trained lacked in the necessary level of realism, albeit failing to understand the increased risks of injury that would surely result because they lacked any real ability to control their techniques.

To put this story into an even clearer picture, the student and her family were all below the rank of green belt. That’s right – a student with less than a year of training was attempting to correct her teacher who has several decades of training and experience.

Back in the late Seventies, early Eighties, stationed in Germany during my first assignment in that country, and after having conducted classes on the German economy for several months I was approached by some young German students who felt my style of training was too militaristic. They felt coming to attention and bowing was too subservient among other things they were required to do during our training sessions. Needless to say, I was somewhat taken back by this affront. Their lack of respect for my years of experience and me as a person, being at least twenty years older than they were, was truly amazing. In the end those students were not invited back to train under me.

How should we deal with students who demonstrate such levels of disrespect by criticizing our teaching style? What is the best way to explain our particular teaching methodology? This will vary depending on how insulted we may feel when it happens, and how much patience we’ve learned over the years. Clearly those of us who are older and have many years of experience as sensei will handle the situation (s) differently than our younger, less experienced counterparts. I’d be lying if I told you I didn’t have a strong urge to put them on their collective butts.

The key point though, that seems to have been lost by the students in the above examples, (besides the obvious lack of respect in their upbringing,) is a trust in the skill level and knowledge of their teachers. Those of us who are parents with grown children can recall when they (then kids) thought they had all the answers, only to find out mom and dad were a lot smarter than they had given them credit for once they had moved out and were on their own. That’s when the parents receive that phone call indicating the light has finally come on for the budding young adults.

Teaching realism requires students to first develop basic skills and knowledge of blocking and striking techniques. Coupled with this is the simultaneous development of their character, which was the key point in Dr. Debelak’s recall of the movie. As the student’s skill and abilities improve they are able to practice with other students in a paced manner that allows them to continue growing in their use of these maneuvers without causing harm to their fellow practitioners, or being injured in return. They also grow in respect and appreciation for their training partners and instructors. At some point down the road, when they’ve become a good Brown Belt, they have a better ability to control their techniques. It’s at this point we begin to expect them to execute their techniques with greater speed, power and control when using them against an opponent. Additionally, as senior under Black Belt students, they serve as good examples for the newer members of the school.

When I competed in my first tournament in May of 1966 in the National Guard Armory in Washington DC, we didn’t have hand and foot pads. About the only protection we wore was a nut cup. Some did have shin protectors, but the majority didn’t. Sure there were injuries: people got teeth loosened or knocked out, or a bloodied or broken nose. However, the vast majority of us had a clear understanding of the importance of control and worked hard to develop it. We also demonstrated the respect we’d been taught by our sensei, which further enhanced the teachings and expectations of our parents.

I feel today’s students have become focused on their own personal desires and goals. They have no real understanding or appreciation for basic respect and courtesy. They also lack the understanding of the importance of control because they’re all padded up when they spar and the need for control is less important and seldom emphasized. Like the student who felt the training was not as realistic as it should have been failed to comprehend, without the ability to control our techniques one moment and not another is what differentiates the true martial arts practitioner from the street thug. These skills are developed over time while practicing control with fellow students and going all out on the heavy bag.

There is a key difference that sets true martial artists apart. The development of humility and self-control results from the process of training over the many months and years leading to becoming a true Black Belt. If one’s focus is only on fulfilling his or her immediate goals of self-satisfaction and aggrandizement, there is little to no concern or respect for others; a sad fact witnessed in various venues.

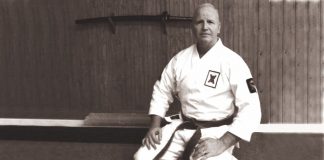

I remember my teacher Sensei Ernie Lieb would kick a cigarette out of a student’s mouth during demos for audiences with little to no knowledge of the martial arts. His abilities were illustrative of years of discipline, dedication to his training, and respect for the instruction of his teachers. Spectacular “yes!” The foundation though, was one of respect a quality much needed in students of our day and age.

So how do you see it? What examples do you have of a similar nature? How did you handle a student who feels you’re not providing them the kind of training they feel they should be getting? Perhaps your response here might be a window to your own views on respect (or the lack thereof).

PS A special thanks to Dr. Debelak for his assistance in helping me word smith this article into one of focus and meaning.