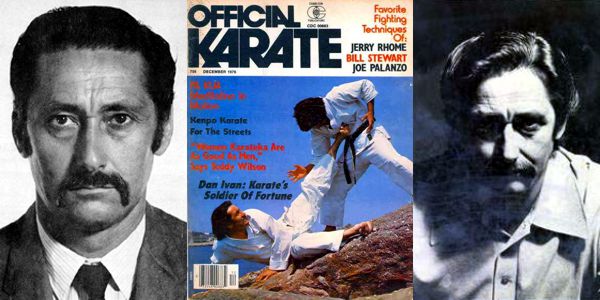

This article by Robert Hunt is about Dan Ivan, martial arts pioneer and icon, taken from their 35 years of friendship and apprenticeship, some long nights of taping, and from Robert Hunts own memoirs. Mr. Ivan began training in Japan in 1948 and spent his life in the martial arts world. The quotes in italics are Mr. Ivan’s own words from things he has written or tapes I have made. Robert Hunt

As I walked through the neighborhood of fallen concrete buildings and remaining ashes of those that burned, the smell of hibachi cooking permeated the air. Looking around in the darkness I could see small flickering flames, fires built in cans to keep warm.

The light bulb swayed back and forth on one almost bare wire, tossing random illumination on the dark staircase below. Dan Ivan stared down the staircase and wondered if karate was worth the risk. The bombed out buildings had the feel of a concrete graveyard and who knew what the shouts from down below meant? Finally he mustered up the courage to take a few tentative steps down and crouched to catch a glimpse of the room. It was filled with Japanese in white karate uniforms and they didn’t look all that happy. It was three years after the end of the war, miles away from where most Americans wandered and worlds away from any place Dan Ivan had ever been.

He eased his way down the stairs until he found the bottom and stood there stationary, not sure what to do. A room full of deceptive Japanese gazes rotated his way and he was certain, at least very afraid, that wartime memories might still prevail. The teacher was short and solid, with shoulder length hair. He held up a hand to stop class and walked toward Dan. Dan bowed, the teacher bowed and Dan offered that he had been studying Judo on the Army base. This teacher happened to know that one and, after a very pregnant pause, finally nodded. He welcomed Dan to sit and watch and went back to teaching class. The brief tension passed and Dan began a friendship with Gogen Yamaguchi, AKA “the Cat”.

But where does one even begin to tell Dan Ivan’s story? And where do you go with it? A more complex person would be hard to find and a person with a more colorful life doesn’t exist. So I guess I’ll begin somewhere around the beginning, and end somewhere around today and see where it all goes.

Trains pass through Alliance, Ohio working their way to almost anyplace else they can find that isn’t Alliance, Ohio. To you and me it would be a dismal place. Danny Vargo sat and watched those trains pass by and listened to their mournful wail at night, and he longed to hop one and go somewhere, almost anywhere. He still does, I promise you.

He was born in eastern Ohio, not far from the Ohio River and in the general area where Dean Martin grew up. It wasn’t an easy life, but who knew? You lived it. You survived. To him life was exciting.

Life was always one big adventure for me. I started hopping freight trains when I was about nine or ten years old, which later developed into more serious situations with the law. That’s why in 1945, at age 15, the Police in Alliance, Ohio dragged me into the Army Recruiting Office. With their help and some forged documents, I ended up in basic training, then off to Guam and the South Pacific.

His mother was a hard working cook who raised most of the kids in the neighborhood, but his grandparents, the Vargos, raised him. At about ten years old he became bored with it all and started to jump on those trains just for the ride through his town. He would hop a boxcar as the train slowed at one edge of town and hang on until the train started to speed up on the other side. One day he just never got off. After that he spent years riding the rails around Depression ravaged United States, living off the land, the people and his ever-present wit.

Eventually he was given the choice of the army or Depression era justice and arrived in Japan shortly after the Second World War. Somehow he got involved in language school, learned Japanese, joined the CID, (the Criminal Investigations Division of the Army), and spent the next years studying karate, judo, kendo and aikido and tracking American military criminals around Tokyo. He hung out with Don Draeger and practiced survival at its root – in the dirty, death filled streets of Tokyo’s underworld.

Walk with attitude, strut and swagger, something I learned as a kid…

That was Dan Ivan in those days. At 130 pounds, he wasn’t big enough to be threatening, so he did it with attitude. And he was tough. One time a few years ago (when he was 70) he was visiting my home in Phoenix. His back was turned to me. I snuck up on him and casually grabbed his shoulder. I felt the muscles in his arm contract like an electric charge and he spun around to face me (when he was 70). He didn’t do anything. He just smiled. But deep in the back of those Transylvanian eyes I got a glimpse of dirty Japanese streets and hard times and somehow I felt that he was probably happiest in Japan, in 1948, a gun on his hip and life in the raw laid out before him.

You can give a litany of his martial arts training, but why? He was there in the beginning and studied from storied instructors – karate with Obata, a karate master in the true sense, and Gogen Yamaguchi, then Aikido with Gozo Shioda. Karate, itself, only found its way to Japan in the 20’s, only really took root in the 30’s, came to almost a complete halt in the war years and began in earnest thereafter. That’s when Mr. Ivan’s career collided with destiny.

A young Japanese man confronted me, blocking my path. Back home in Ohio this was the way fights start, so I laid into him first with an Osotogari leg hook throw, something I was developing at the Kodokan for the past few months. A good throw, but my adversary, flat on his back, practically bounced back up and hit me in the mouth with a straight right hand. I took notice that a semi circle of men formed around me, obviously his friends. My plan was to dump him and split. No way could I handle all of them. Instead, he and his friends took off, disappearing into the crowds that were gathering. That seemed like a good idea, so I did too.

Fifty years later Mr. Ivan still talks vividly about those times. Fights, stakeouts, beatings, betrayals, the proximity of death. Karate wasn’t a game for him on a clean, matted dojo floor like it is for most of us. It was survival on the filthy streets of Post War Japan. He talks about going down to Okachimachi looking for heroin peddlers, people who trafficked in the infamous “China Snow”. Most humans have never even seen heroin let alone dug a peddler out of a rat hole. Now Okachimachi is a stop on the Tokyo railroad line but, in those days, it was a cardboard box town that could be rearranged in a few minutes to keep intruders out – or in. He recounts the fear he had going in, of confronting the bosses there. But, when you get to know him, you can only think that maybe that fear was what kept the blood pumping through his veins.

His later years are more renowned – one of the first karate schools in Southern California, karate productions at the Japanese Deer Park, a million dollars in Real Estate, Movies, Las Vegas Productions, Tournaments, enough accolades to fill several lifetimes. But late at night in his quiet, humble house in the desert outside of Palm Springs, that’s not what he talks about. Japan is what he talks about, and life in the maelstrom of adventure.

Things in Ueno-Asakusa machi were volatile, the war weary residents had no more regard for the Police than they did for me. It was understandable, the entire nation was starving, and when you don’t have a place to sleep or food for your children, then…

He tested for his Kendo black belt not sure of what to do. He had traveled all night. He was tired. He was on unfamiliar ground, but he wasn’t going to give them an inch. He screamed and attacked. They stared at him like he was some bizarre demon, but they gave him the belt. He still thinks that Kendo training is a great way to learn to fight.

You learn to close distance quickly.

When Mr. Ivan talks about fighting, you listen for a while, then you realize that he isn’t talking in the abstract, he’s recounting fights he has had. “Attack the eyes, then the legs, then the throat or solar plexus. That way you take away the vision, the legs and the breath.” I thought he was talking about kata or something, but he was talking about the scum he did battle with and how he survived.

I have sat and listened on countless evenings while Dan Ivan talked about his life and his adventures. I taped many of them. Sometimes I walked away laughing, other times I walked away wondering what kind of childhood could temper such a human. But I always walked away talking about it. It was always something different. Sometimes I shook my head. Sometimes I lamented not helping out more. But I never walked away bored.

I was born and raised during the ‘depression’ in United State, a time when we had too little to eat, no jobs and a bleak future. Frankly speaking, everything that happened to me before entering the Army could have earned me a long jail sentence. From the very beginning, I empathized with the Japanese.

A few years ago Mr. Ivan was awarded an eighth degree black belt from the International Martial Arts Federation. A Zen priest handed him the award, a descendant of Tokugawa the first Shogun of Japan. Mr. Ivan was proud. He was impressed that someone of that stature had presented him an award. But what could that Zen priest possibly offer Dan Ivan? A number? A piece of paper with Japanese writing on it? Stature in the martial arts community? He is the man who embodies stature, not from paper awards, but from a lifetime of training and respect. He is a man who has witnessed life first hand, who has seen more than you or I in our wildest dreams could ever imagine. That high-bred Zen priest, contemplating life from a polished hard-wood floor, has nothing to offer this human who has contemplated life from the inside out and the bottom up. Who should present whom the award?

Most karate people are fakes and if you ask them and they are truthful, they will admit it. Most couldn’t fight their way out of the proverbial paper bag, not because they aren’t tough, but simply because they’ve never faced anything resembling death, the great equalizer. I haven’t and I’ve been studying for forty-four years. I’m not sure what I would do if faced with someone who actually wanted to end my precarious life. But Dan Ivan does. He knows exactly what he would do. He’s already done it.

A hundred and fifty years ago Okinawan Bushi used karate to defend themselves, bring bad guys to justice and fight the good fight. But not long after that, karate became little more than the hobby we pursue today. Dan Ivan’s life is one of the closest I can find that parallels the lives of those early Okinawan Bushi. He faced life and death, defended himself with his martial art and fought the fight, good or bad

I scrunched up in the corner, gripping my club in my right hand. Tears began to flow uncontrolled, but silent – dry tears. The bums at the other end of the boxcar wanted to see some weakness from me, then they would attack to take any valuables I might have. It was something I learned how to do, remain stoic, expressionless, cry on the inside, but never let anyone see. At that very moment I was a real thirteen year old, missing my Mother, Grandmother and Grandfather back on Homestead Avenue in Alliance Ohio.

Mr. Ivan started his dojo in Southern California in the mid-fifties and was always recruiting students. He wore long hair in those days, years before it became fashionable. Once a car-load of tough guys cut him off in traffic. He chased them for a while until they pulled over. He stepped out, his long hair blowing in the wind, and strolled to the side of their car. Apparently they guessed right that one lone, skinny guy with long hair must have been a little nuts to go after a car full of toughs so they decided to stay where they were, locked the doors and roll up the windows almost to the top. Mr. Ivan pulled karate business cards out of a shirt pocket and slipped them through the cracks at the top of the windows, trolling for students anywhere he could find them.

Dan Ivan created many of the karate “masters” who populate today’s magazines and stories. He promoted them in the early days and put them in the forefront. One old Japanese hadn’t even been in a dojo for 20 years when Mr. Ivan introduced him back into the art, got him going again, set up a tournament for him and promoted him simply because he had been around in the old days. The guy, now deceased, has almost become an icon in the karate world. If it weren’t for Mr. Ivan he would still be a reprobate. I was there, I saw it happen.

Magazines need people to write about, so they create heroes. That’s all right, we all like success and Mr. Ivan has been written about as much as any. But there is a difference. Dan Ivan lived the life, and walked the walk. He owes who he is to no one, no magazine editor or tournament promoter. No one created him, he created himself, faced death and lived to tell about it.

I was just a two-bit juvenile gangster back in Ohio, now suddenly its like the universe wanted to shape me up, give me a major attitude adjustment.

Dan Ivan, now in his seventies, lives a secluded life in the California desert facing his own date with eternity. He takes it day by day and hopes for the best. The same perseverance and determination that kept him alive in Post War Japan keeps him alive now, and life still holds the same adventure it always did. In the quiet desert night, I sit and listen to old stories, knowing that they will not always be there to hear, and trying to absorb as much detail and feeling as I can, and to understand what made this person what he is today and why. Coyotes occasionally howl. I think they know who we are by now. The night descends further around us. I take a deep breath and contemplate eternity.

It’s hard to know someone. People aren’t easy to understand and Mr. Ivan is more complex than most. I don’t judge, I just listen and I try to be the best friend and student I can. That’s pretty much all I can do. When I give him this manuscript to look over, he will tell me to change it, that he will be embarrassed by it, ashamed to walk down the street, but I won’t change it. This is the truth as close as I can find it.

It was a cold dismal night in Tokyo, 1948, during the American Occupation of Japan. I had entered the Ueno, Asakusa district, a ravaged war-torn no-mans-land, off limits to allied personnel. It was off limits for good reason, a breeding ground for criminals, whose primary source of income was the black market, robberies, prostitution and general illegal activities. Of course that described nearly all of Japan during that time, except here it was a little different. It was teeming with residents who had little use for a round-eyed Yankee like me, especially the homeless veterans of the war that still harbored resentment and hatred for Americans. Little did I know at that time in my life that destiny might have already charted my course. Despite my hostile surroundings, I was at the right place at the right time and on the precipice of a new life.

Editors Note: Dan Ivan Sensei passed away on Wednesday, November 14, 2007 of bone cancer at the VA Medical Center in Loma Linda, California.