This veteran smith has devoted 35 years to perfecting the 1911!

Everyone is familiar with the, phenomenon of mid-life crisis, and it seems to be an unavoidable event for one and all-even ace gunsmith Terry Tussey.

Tussey is a pistolsmith well known in Southern California shooting circles for tuning police pistols and building “business guns” of the Colt 1911 variety. A working gunsmith for 35 years, Terry narrowed his focus to the aforementioned services a couple of decades ago and seemed content in his niche, but recently he is showing signs of having finally snapped under the pressure of contemporary society.

Tussey didn’t swing out wild as some men do-leaving their families, adorning themselves with gold chains and chasing younger women-but his departure from the established norm was just as radical for him: he began building exotic raceguns.

I guess it started with a compensated gun here and there, then a couple of optically and gunscribes nowadays to refer to the most current and exotic configurations of pistols used in speedshooting competitions.

Then I’ll backtrack a little to point out that for many years the “street guns” that Tussey built were the raceguns of the day. In fact, it was 1980 before John Shaw would use his Clark Pin weighted muzzle to win the IPSC Nationals and any major differences became visually apparent between the full-blown competition guns and a stock Colt. Finally, I suppose it’s clear that I’ve taken this opportunity to have my fun with friend Tussey, but let me state now that he is one of the few men I know personally who truly understands how the “knee bonz’ connected to the shin bonz”‘ when it comes to the 1911- design semi-auto pistol.

This fundamental knowledge is evident when you converse with the man, and his meticulous nature is easily recognized when examining his work.

Terry has not really abandoned his former stock-in-trade work, and in fact he is as busy as ever in that venue. The raceguns are but a small part of his repertoire, which includes something as simple as a “Tussey Reliability Package” on the 1911, or it can range out to the aforementioned racegun.

The bread-and-butter work from Tussey Custom begins with the Reliability Package, which includes the normal complete inspection, function check and ramp/throat job but also involves other operations.

Additional work includes polishing the breechface of the slide, beveling its bottom edge and polishing the underside rail of the slide that rides over the top cartridge in the magazine before it picks it up on the return stroke. Tussey also scoops out the disconnector well with a special scraper from Brownell’s that assures the disconnector floats freely.

Tussey checks and assures the barrel chamber dimensions by cleaning it up with a finish reamer. Using a tap handle and doing it by hand gives him the feel of the job.

Terry comments that more often than not he discovers problems with all but the most expensive match barrels. This is generally traceable to two factors: worn reamers used in manufacturing or chamber distortion caused when the barrel hood was roll-marked.

Adjusting extractor tension and function testing the gun finishes the job, and those extra touches make all the difference -evidenced by the fact that one of Tusspy’s favorite demonstrations at the gun shows is to cycle a magazine full of empty cases through one of his guns. That sort of tells it all right there!

Making them work is one thing, but making them shoot is another.

“Accurizing” is a popular buzzword that encompasses a whole spectrum of operations, but authorities agree that the three most important areas are the trigger, the sights and the fit of the barrel.

Good trigger jobs are often described as feeling like the shooter’s finger has “just snapped a glass rod” or as “surprising you with every shot.” This is fine for the bull’s-eye target shooter but hardly recommended for speed shooting or business guns, which require a little more sear engagement to be safe and practical in their intended applications.

The trigger on my custom .45 from Tussey breaks cleanly at nearly 4’/ pounds, but Tussey’s skill and the Wilson Ultralight Match Trigger combine to make it feel more like three pounds. I have shot some of the best handgun groups of my life with this gun, and I actually went so far as to have him build in a little takeup to the pull as an extra precaution-so don’t lean too heavily toward light trigger pulls as an absolute requisite for accuracy.

This gun is a 1991 Colt that Tussey worked over with parts exclusively from Wilson’s Gun Shop. The pistol came with the Series 80 safety mechanism, which Tussey would have refused to disable if I had asked-although I didn’t. (Terry and I agree with Bill Wilson’s comment in his book The Combat Automatic that “it’s really not such a stupid idea to have a gun that won’t shoot you in the butt if you drop it.”)

The big gripe with the Series 80 safety is that many smiths can’t seem to get an acceptable trigger job with the trigger/firing pin interlock parts in place. Tussey has no problem achieving a commendable state of affairs with all safeguards intact, but he’s the first to admit that it takes a good deal more time than it takes with a pre-80 gun.

One of the reasons for this is that all the safety interlock parts have to be checked for fit, polished and have critical bearing edges beveled to eliminate the common problems of catching, sticking or that sensation of parts “stacking up” until the gun fires.

Tussey has a supply of Series 80 parts, and he interchanges pieces until he finds a set that interacts properly, then polishes them out and fits all to the specific gun.

Pre-Series 80 work is normally quicker and easier in most instances, although I did recently watch Terry spend over an hour getting a proper sear-to-hammer engagement on a gun. It turned out that the Springfield frame and sear positioning didn’t line up well with the Colt hammer being installed, resulting in sear contact on one side only.

The gun seemed to function correctly. The hammer (for now) would not “bounce down” when the slide was slammed shut, and the trigger broke cleanly-but Tussey’s deft trigger finger noticed something wrong, and sure enough, the marked parts showed no evidence of contact on the one side. The Dye-Chem marking finally testified to proper mating of the parts, but not until Tussey had lowered the one side of the sear until the piece looked deformed.

A pistolsmith of lesser experience and diligence than Terry Tussey would have never known the difference!

Sights are, have been and always will be a personal issue. Tussey will install just about anything you like, but he prefers the Millett adjustables on guns that wear movable fixtures because the rear sight body dimensions are concise and consistent, making it a simple trick to cut the slide and do the installations.

My Tussey/Wilson .45 wears the Millett adjustable night sight, which uses the bar-dot-bar elements in the sight picture, eliminating any confusion under stress about which dot goes where!

Fixed-sight Tussey guns wear either the Novak or Millett rear unit, and again Tussey uses the Millett front sight blades because they can be installed (and removed again) after the slide has been plated or blued, making it easy to zero the fixed-sight guns to a certain load.

Barrel installation and fit in the 1911 is an art of its own. This is because the barrel not only needs to lock up snugly, but it must also be centered within the slide. A simple concept, but one overlooked by many and misunderstood by many more.

Locking the barrel up tightly provides the mechanical assurance that it will shoot to the same place every time within the limits of the tube itself; however, in order to get the piece to shoot along the line of the sights, the barrel must be parallel to and centered underneath those sights!

Technically, a gun can be zeroed only at one exact range. This is due to any offset of the barrel-to-sights, and the elliptical flight of the bullet.

Sight settings create a zeroed startpoint for elevation at some given range, and eyeball estimating proper drop with pistol cartridges at extended ranges is nearly impossible. However, it is easy to see that lateral off-kilter barrel-toslide/sight alignment is why your 1911 shoots so far to the left or right when you plink away at the rock in the dirt bank 100 yards away. Some extreme cases will even need a click or two of windage to go with elevation changes between 25 and 50 yards.

Tussey formerly used a sized and de-primed cartridge case to regulate his barrel installations, chambering same and sighting through the firing pin hole in the stripped slide to center hole-to-hole on the rear end. Nowadays he uses a gauge made for the purpose from Brownell’s.

Here is where I’ll mention that Terry does a welded-barrel accurizing job that replicates the fitting procedures used with the oversize match barrels.

The normal weld-up technique merely builds up the bottom lugs of the barrel, and then uses longer barrel links to jam the breech end of the tube up into the slide. Tussey does it differently, using a TIG welder to prevent hot spots or detempering the barrel steel, and having the three sides of the barrel hood extension built up. He also has two “pads” laid into the channel of the barrel locking lug just ahead of the chamber.

Fitting the barrel is the same then for new match or re-welded units, with Tussey measuring out the subject slide and precisely milling the barrel hood to mate into that chamber area window. Vertical relief and lateral alignment is a matter of fitting oversize lugs (or those welded pads) with a proper lug file until the barrel is centered on the firing pin hole.

There is an exception here with Clark or other barrels that don’t use the “new” National Match design shallow bottom lugs in their design. These barrels are intended to be set completely up into the slide, and an offset firing pin bushing (also from Clark) is used to redirect the tip of the pin to a center-strike on the primer.

Centering the chamber on the firing pin not only helps align the barrel, it also helps produce a more consistent pin strike-therefore creating more positive and consistent ignition of the cartridge. Not a big issue for a .45, but an important matter for the guy using hot loads and rifle primers in his 9×21 or .38 Super.

On the other end of the barrel, the bushing or barrel-cone fit is what separates the men from the boys here, and Tussey does his on a good-sized lathe, hand-finishing with his trusty Electer tool.

Okay! Okay! The guy can build a gun! But what about these raceguns?

Well, I defend my lengthy preface by pointing out that like any work engine designed for rough use, the 1911 relies upon being fitted to a certain set of tolerances and fed a standard fuel-at which point it delivers a consistent level of performance.

Changes in the system are just that, an alteration-to a previously balanced mechanism, and if another point of balance is not achieved, you get a gun that doesn’t work or can even be dangerous.

This sounds simple enough, but there are plenty of horror stories about problem guns making the rounds of owners and “qualified gunsmiths” in any shooting clique to belie that first impression. I myself know shooters who have lived through the nightmare with hot-rodded guns, and many of you have probably witnessed the same. So, what is pleasantly unique about Tussey’s guns is that not only do they work, but he knows why! Terry brings this comprehensive view of the system forward with him when we deal with altered projects, that is, raceguns.

I also understated Terry’s background with the compensators and such, since he has actually been building them for years and today offers a variety of compensated competition and personal pistols-notably his Stealth Comp unit, which is carved out of the front of the slide, leaving the pistol at standard exterior dimensions.

(My favorite of Tussey’s personal guns is a cute little Officer’s ACP with its normal .45 ACP top end and another very trick .38 Super unit that is made from a cut-down Commander slide. Featuring a Stealth Comp, it is the same size as a standard Officer’s ACP but a lot more shootable. Tussey’s hand-made magazines hold eight rounds, making it a potent nine-shot pocket gun!)

High-capacity aftermarket frames have been the rage for some time now, and a peek at the Gun Digest Book of the .45 (Dean Grennell, DBI Books) will show Mr. Tussey in there doing a plain vanilla build-out on one of the first units from Para-Ordnance for the author.

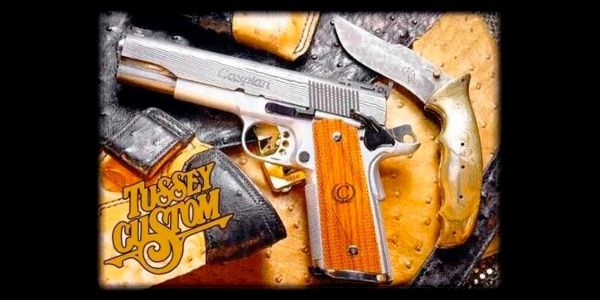

Terry works with all three highcapacity aftermarket frames, his finished products being such that Caspian Arms borrowed the racegun built on their frame seen here for their display at the 1993 SHOT Show.

I am in the queue now for some attention from Terry regarding my new modular receiver from Tripp Research, which I want to have mixed together with a compensated Caspian Hybrid -top end in .45 ACP

Tussey also has been experimenting with the skeletonized slides in different permutations, having some successes in his endeavors, -which includes the normal T handles and so forth.

The jury is still out on the best way to relieve the part to lighten it without sacrificing its structural integrity, and the sub-calibers (9×21 and .38 Super) are quite load-sensitive.

Anyway, Dear Reader, I didn’t format this article in such a backward and short-ended manner to be coy or precocious. I did it because I presumed you’d already waded through all the standard racegun adjectives many times before-and that this time you might appreciate hearing the views of a relatively littlecelebrated, but still very competent, pistolsmith.

Certainly his guns do all of those expected things in terms of accuracy, dependability and shootability that you read about monthly-but you already knew that, didn’t you?

If the Art Department and I have done our job, the pictures should convey at least the minimum 1,000 words each about craftsmanship, innovative design, attention to detail and aesthetic styling.

Finish work like this doesn’t make them shoot any better, but I’ll tell you, it’s a sure indicator of the rest of the effort-and I think at least I shoot better with guns like this!

I wouldn’t have believed there could be such a talented guy available at reasonable rates who wasn’t overrun with business until I met Terry, and in spite of my own good sense, I’m going to spoil that by letting out the secret.

The good news is that Tussey himself still has a decent turn-around time on work-and the better news is that there may be a Terry Tussey near you! All you need to look for is a guy with a few decades of experience, an encyclopedic knowledge of the 1911-creature and a commitment to excellence!

Custom Pistol Tuning With Terry Tussey

By Paul Hantke

Handguns Magazine

January 1994