Unfortunately, most civilian martial arts training fall short in the area of team communications and teamwork, because there is an assumption that the martial artist will be a sole defender.

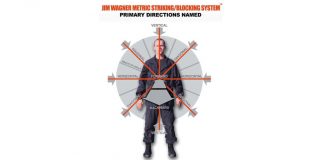

On American warships the front of the ship is called the bow, the rear is called the stern, the left side is called the port, and the right side of a ship is known as the starboard. These words, so I’ve been told while participating in Maritime Interdiction training in the Port of Los Angeles with United States Navy and United States Coast Guard Special Operations teams, revert back to plain English “Front!” “Back!” “Left!” and “Right!” in times of combat. Thus, when you are coming up to a narco-terrorist’s drug smuggling speedboat you don’t bark out, “Turn to the starboard!” but rather, “Turn right!” Similarly, when I was a team leader recently on a Military Police protective services detail for the Governor of the State of California and the top Army General of the State of California, my team had a simple “combat language.” When protecting “the principal” (a term which refers to a diplomat, movie star, high profile prisoner or any VIP, or Very Important Person, needing protection), and an attack is launched against this person (be it an attack with a gun, hand grenade, or a just a pie in the face), we use one of four, to-the-point warnings: “Threat front!” “Threat rear!” “Threat left!” or “Threat right!” Regardless of the means of attack, the counter-assault and evacuation process will be initiated without hesitation based upon the direction called out by the engaging soldier who is member of the team. Thus, police codes, military acronyms, or complex phrases are ditched in times of stress in order to effectively communicate the urgent message, since there might not be a second chance to clarify or repeat it. So what do these two examples have in common, and how does it relate to civilian self-defense?

Teamwork, Teamwork, Teamwork

In military and law enforcement circles, teamwork is an essential element to operational success. To have effective teamwork requires clear and concise communications between members of the team. It doesn’t matter if the team is made up of two police officers making a car stop on a country road or a 140-man counter-terrorist team hitting a compound in a foreign country to rescue hostages or “eliminate” a high-profile terrorist, good communication during conflict is just as important as using the proper tactics and techniques. Right from the start, be it in Boot Camp or the Police Academy, recruits are taught how to properly communicate with each other in routine and crisis situations, and it continues throughout their careers. Unfortunately, most civilian martial arts training fall short in the area of team communications and teamwork, because there is an assumption that the martial artist will be a sole defender. This mindset is evident when we take a close look at most martial arts schools when it comes to sparring (one-on-one), katas (solo performance), and the tournament environment (which is based on sport rules, and again one-on-one). The majority of martial artists train for one-on-one situations or one vs. multiple attackers. Yes, this type of training is necessary, but there are very few civilian schools that teach multiple defenders who must work together for mutual survival, be it against one dedicated attacker or many attackers.

If you, the martial artist, trains only to protect yourself, and you do not train to work and communicate with those engaged in the conflict with you, then the odds of failure increases. Although self-preservation may be the primary action in some group situations, abandoning persons involved in the crisis with you may not be an acceptable or moral option.

Since it is likely that you may be fighting along side others in a real conflict situation, you must incorporate techniques and scenarios that deal with such eventualities into your training regime.

Command Presence

Most people tend to “freeze up” in violent crisis situations. When confronted with harm their voice cracks, their eyes display panic, their breathing is rapid and shallow, and they may display shaking, crying, moaning or other signs of fear. You must be the person who can immediately assume the leadership role, the “voice of reason” so to speak, in a crisis situation. In copspeak this internal control is called “command presence.” Command presence means having “the appearance of calm.” This means a strong authoritative voice, and well thought out actions that once acted upon are carried out as intended. The person who seems to appear self confident and sure of what action should be taken is usually the one people tend to follow.

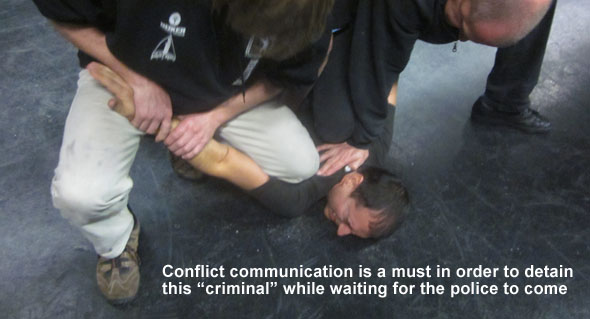

In civilian martial arts training command presence can be accomplished through scenario training. For example, one person assumes the role of aggressor, one person is the defender, and one or two other students are to be protected by the defender because they are afraid or unable to offer any assistance. Just prior to the fight (this could be done with light contact wearing the proper protective gear) the defender must show a strong command presence by ordering his protectees to get to a safe spot in the room or order them to call the authorities on the cell phone. It sounds elementary, but in times of crisis people will just stand there and do nothing. Often times you have to “jump start” some people into action, “Stand over there and call the police. Now!” Just like on warships, or the orders given to a bodyguard team, all communications must be in plain simple language and loud enough to be heard by all.

Direct Control

Let’s say that you must protect a six-year-old child; yours own or somebody else’s. A couple of attackers are trying to harm you and the child. If you just start swinging away without a plan, that child could run off and into the arms of one of the attackers. A “direct control,” communicating through action, response would be to grab the child by the hair with one hand and pull that child to your backside using your own body as a human shield, and hold them there. By doing this you will know where the child is at all times, and you can move together as a unit. Grabbing a child by the hair may sound cruel, but it is the only way to adequately protect the child.

Another example of direct control may be in a situation where you must force a person you want to protect to the ground during a shooting. This may sound easy, but how are you going to accomplish it? Are you just going to tackle them to the ground and then jump on top of them? What if they resist you? These are techniques that need to be practiced before actually applied.

In actual shootings most people just stand around seeking no cover or conceal for the first several seconds until it finally registers in their mind that they are in real danger. Most people interviewed by the police after a real shooting state, I thought it was just fire crackers at first.” This may sound funny, but I’ve actually seen a shooting where everyone stood frozen like a deer caught in headlights as the gunman fired rounds. Anyone caught in that situation is going to be frozen for a moment or two, but with good training and good communications, the response time can be reduced.

One easy direct control technique that you can use to bring someone down safely to the ground in a shooting incident is to get behind the person you intend to protect, reach around their waist with one arm and bend them over with your other hand by placing it on the back of their head and pushing them downward. Once they are “folded,” and you trip them with one of your legs to get them onto the ground, you can order them to stay put (using your command presence) and go back to the fight; or shield them with your own body depending on circumstances.

Until you have actually practiced direct control movements they will not be smooth, or may not even work effectively. That is why in your training you must practice using direct control. One easy way to practice this in a training environment is to have a training partner stand near you, and when the instructor yells out “Bang!” or fires a few air gun rounds, you practice taking that person to the ground a few times. Each time the person you are taking down should be standing in a different position at different distances. By practicing this, you will soon discover what variations of the technique works best for you.

A second example of direct control is to be side by side with a partner ready to take on three “thugs” (students selected as the aggressors). The direct control technique would be to immediately shove your partner toward one of the attackers and give the order, “You take on that guy, and I’ll take these two!” By doing such a move and interjecting conflict communications you have formulated an immediate plan, you have communicated it to your partner using good command presence, and you have begun executing the plan by using direct control. This is conflict language and teamwork at its best.

Follow Through

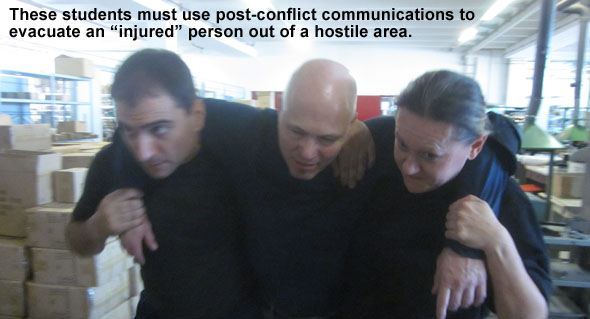

Once a crisis is over you must have the presence of mind to deal with the aftermath, or as we call it in the Jim Wagner Reality-Based Personal Protection system post-conflict: injuries, preserving the crime scene, calling the authorities, evacuating people, or whatever the case may be. Often time survivors are in a state of euphoria, fear, or disbelief and just stand around as their mind and body attempt to establish normal and routine baseline patterns again. However, if you’ve got other people to worry about around you, you don’t have the luxury to just reflect on what just took place like an untrained person would do.

There are many ways to prompt martial arts students to work on their post-conflict responsibilities. One example would be to have an attacker armed with a rubber knife attack two “victims” who need testing. After a few slashes and stabs the attacker retreats from the scene. Immediately after the retreat the students will most likely just stand around and reflect on what had just transpired. However, before lag time can set in the instructor (a second or two after the attack is over) yells out, “Your partner has a sucking chest wound. Render him first aid.” Another example to do after the scenario is to say, “Get on the phone (pretending of course) and call the police and give them the location, a description of the suspect, and the direction and method of flight.” This jump-start command will remind them of what needs to be done immediately after the conflict scenario. Most traditional martial artists or sport-based martial artists just bow to each other after a fight, and that’s that. So, for many who have had this conditioned mindset doing reality-based training is a radical departure from the norm, and constant reconditioning coaching (jump-start commands) are needed.

Post-conflict communications is a great teaching tool because it also teaches the student that a crisis doesn’t just end when the hostilities cease. This is just one more “tool” to teach the full spectrum of conflict; not just the punches and kicks.

The more you incorporate command presence, direct control, and post-conflict communications in your training with other motivated students, the better you’re going to handle real situations involving multiple people you take charge over. Yes, it’s still important to practice sole defense situations, but the odds are greater that you’ll have other people with you during a real self-defense situation. So, why not train for situations most likely to happen. Adding this to your training makes for more realistic training. More realistic training means more realistic responses, which ultimately translates into saving of lives.

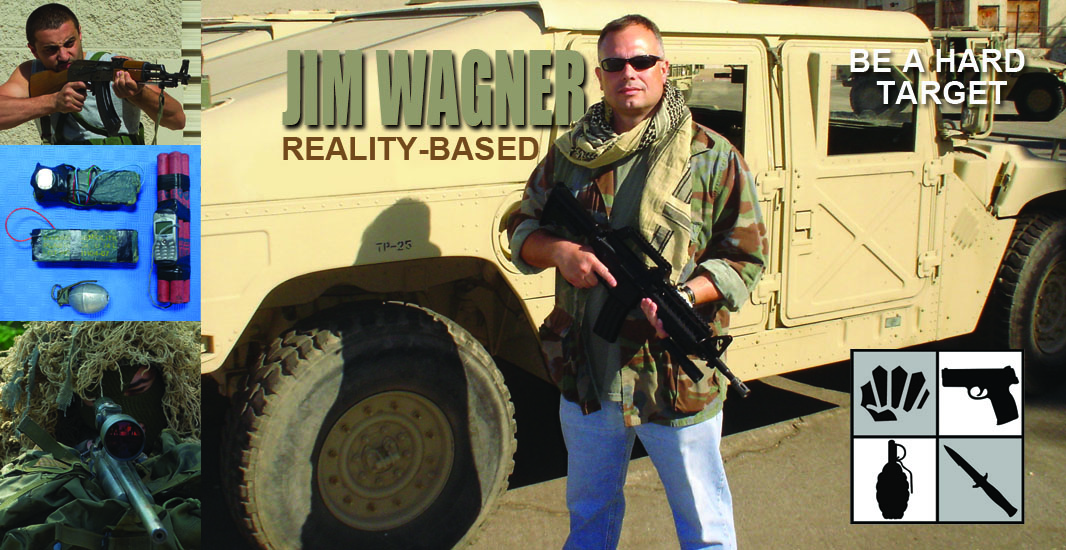

Be A Hard Target.