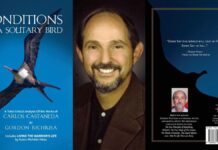

In 1968 Christopher Goedecke (Hayashi Tomio) took his first formal martial arts class. The thrill never left him. Today, martial art is his way of life. A teenage dream exceeded! He holds 8th Dan in Okinawan karate, a fruitful teaching career, and initiation as the Buddhist monk, Hayashi Tomio, that allow him to explore and share Esoteric martial teachings.

When Christopher Goedecke’s fist short story, Wind Warrior, got published in 1978’s, another avenue for his passion opened, writing about the martial arts for children and adults. His books include; Wind Warrior: Training of Karate Champion; Smart Moves: A Kid’s Guide to Self Defense; The Soul Polisher’s Apprentice; The Unbreakable Board; Internal Karate, and lots of articles and short stories for the trade magazines. Current articles are about his favorite subject—the cultivation of Internal Power. With his passion holding strong he promises more books and articles to come.

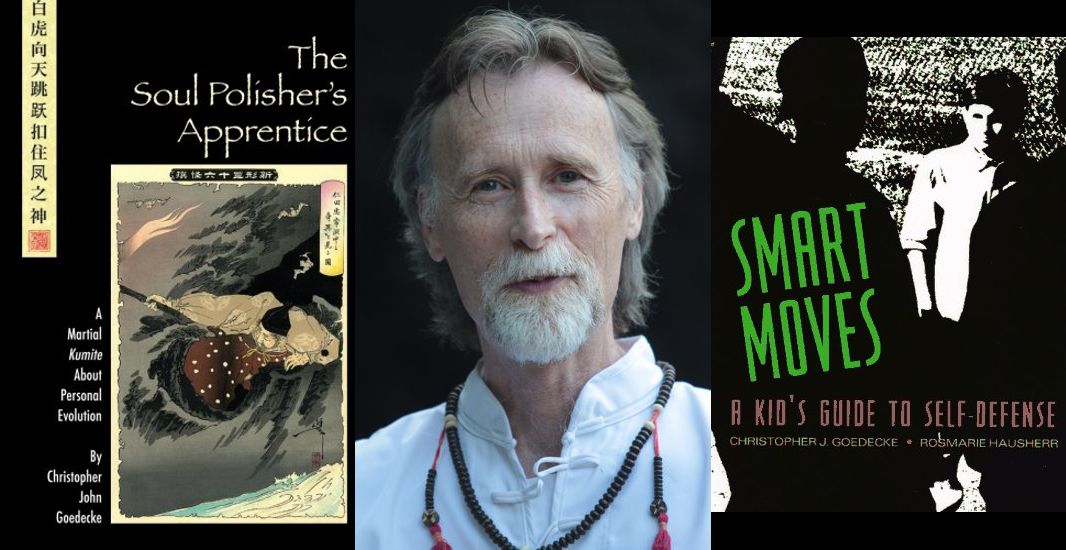

The Soul Polisher’s Apprentice: A Martial Kumite About Personal Evolution

In The Soul Polisher’s Apprentice: A Martial Kumite About Personal Evolution you will discover an American martial renaissance as it claims the heart of Asian fighting arts practice! Become a hae (fly) on the wall in the innermost chambers of martial knowledge. A true, down-to-earth, clearly presented and insightful unfolding of the inner martial journey as it winds through the training hall and into the personal destinies of two contemporary journeymen, Hayashi and White Tiger, who come to embrace the essence of authentic Martial Ways. Penetrating, positive, and refreshing insights are revealed about the nature of martial techniques, rituals, philosophy and spiritual wisdom.

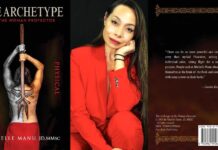

Smart Moves: A Kid’s Guide to Self-Defense

Smart Moves: A Kid’s Guide to Self-Defense is a practical strategy guide enables young readers to prepare themselves mentally and physically for dangerous situations as brought on by bullies and other attackers, and emphasizes self-control, prevention, and communication

Editorial Reviews

From School Library Journal

Grade 4-7-This title puts karate out in the real world, where kids are more likely to be antagonized by bullies and bigots than ninjas and samurai. It covers basic skills, such as stances, blocks, punches, and kicks, then shows how they’re used in self-defense techniques to help a victim escape from intimidating strangleholds, bear hugs, and grabs. While a book can’t take the place of actual instruction, this is a great starting point for learning key points to survival and resolving conflicts, often using nonviolent skills. One of the best sections presents specific dilemmas-a friend loses his temper, a stranger in the elevator seems suspicious, a gang uses peer pressure to victimize others-and their solutions. Numerous black-and-white photographs illustrate the text. A resource list of conflict-resolution sources helps make this not just another stock martial-arts book. Terrence Webster-Doyle’s Facing the Double Edged Sword (Atrium, 1988) is a similar manual with a conflict-resolution bent and a bit more emphasis on nonviolence. Both volumes provide important alternatives to the rampant indoctrination and victimization by violence that today’s children face.

Cathryn A. Camper, Minneapolis Public Library

Copyright 1995 Reed Business Information, Inc.

From Booklist

Gr. 6-8. Self-defense cannot be learned from a book. The practice necessary for learning martial arts techniques is inherently too dangerous to be undertaken by unsupervised kids. Young people are too volatile and immature to make appropriate use of self-defense training. These are certainly valid arguments, but they do not address the acceleration of violence in children’s lives today–in their schools, neighborhoods, and homes–and children’s increasing need to protect themselves. Goedecke, a martial arts instructor, and Hausherr, an author-photographer with many children’s books to her credit, challenge prevailing conservative thought with this “sourcebook of safety and survival strategies.”

At the outset, they encourage kids to join a defense class, and provide plenty of good black-and-white photos of youngsters learning techniques properly with a sensi. Because they also recognize the inevitability of kids’ trying techniques on their own, they do their best to explain the risks and set clear guidelines that unsupervised children can rely on when they practice with peers. The authors begin by explaining the physical effects of anger and by taking a look at the various ways anger can be dealt with. They are conscientious, cautious, and clear as they go on to describe specific self-defense maneuvers, which range from achieving a stable stance to blocking punches and escaping choke holds. Throughout, they forewarn readers, encouraging them to think in advance about threatening situations and opt for nonaggressive action first. Their five-step plan for dealing with bullies is bound to draw some attention, but it’s the book’s final section that will really start kids thinking about personal safety. Eleven authentic, progressively more menacing conflict scenarios, which beg for classroom discussion, are presented, along with suggestions for appropriate responses. This is all very serious stuff. The authors know that, and they make sure their readers do, too, emphasizing over and over that self-defense isn’t about invincibility, striking first, or retaliation–it’s about not getting hurt, and about staying alert, being smart, and acting wisely in a risky world. Stephanie Zvirin

Comments are closed.