Possession of profound knowledge is of great value.

Katsu Kaishu (1823-1899)

While researching the history of martial arts, I am often impressed by the sustained dedication and conscientious exertions displayed by the early non-Japanese writers. Not only did they introduce Japanese martial arts to the world but at the same time they also provided the international community with an access route enabling scrutiny of Japanese culture. The efforts of the below-mentioned four scholars and British Jujutsu pioneers clearly demonstrate this phenomenon.

Before 1850, few Japanese had detailed knowledge of jujutsu and hardly any non-Japanese had even heard of the name. One of the first ever major reports to appear in the US English language press described a display of jujutsu held at Eiichi Shibusawa’s summer residence in Asakuyama on August 5, 1879. This event was staged in honour of US President Ulysses Simpson Grant’s visit to Japan during his world tour. Incidentally, one of the youths performing jujutsu that day was eighteen-year-old Jigoro Kano. Somewhat later, a further significant boost to publicity came with the inclusion of an article on jujutsu that appeared in Lafcadio Hearn’s famous book Out of the East: Reveries and Studies in New Japan that was published in 1897 by the Houghton Mifflin Company of Boston, U.S.A.

The majority of those Japanese who did have some understanding of jujutsu at that time often lacked the essentials, thus there was widespread ignorance as to its exact nature. The main reason for this dearth of detail was that jujutsu skills were kept secret. All written documents, or densho, that were extant were vague in case they fell into the wrong hands thus this documentation purposefully gave little clear factual information. Unlike judo, the finer points of the numerous jujutsu tricks were jealously guarded and passed on only by word of mouth. Because of this tradition, techniques were, whenever resorted to in battle, effective, since the ignorant, hapless victim of an attack had little reliable means of defending himself. Those of the non-samurai classes who wished to learn the art had to first locate a master and if accepted by him, pay a tuition fee for each technique taught. However, tradition had it that it be given only to trustworthy men of perfect self-command and unimpeachable moral character.

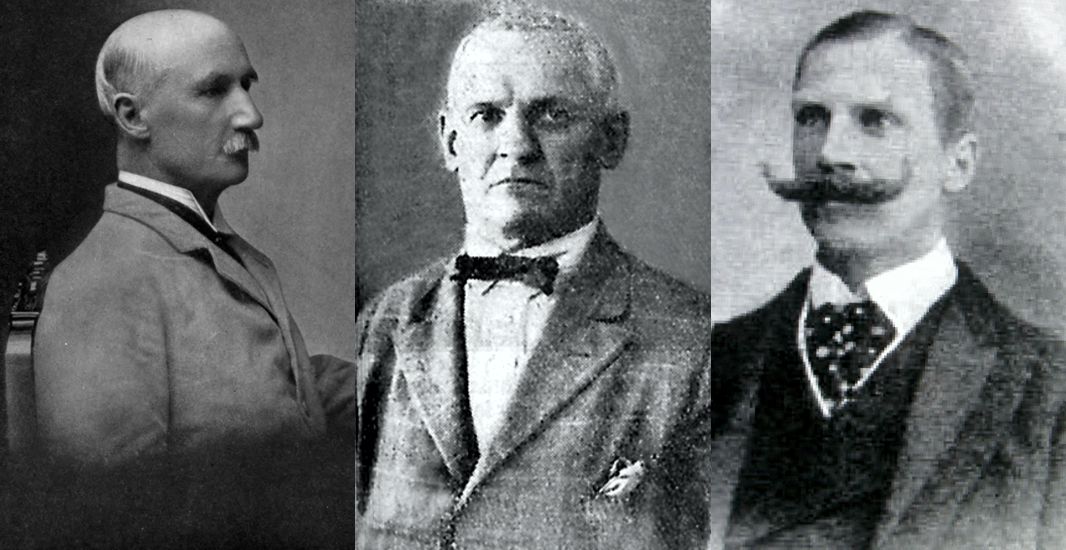

Dissimilar to many styles of wrestling, jujutsu know-how does not usually call for much strength in order for it to be effective; rather speed and accuracy in delivering atemi strikes to the exact location are required for maximum effect. The skilled jujutsuka therefore acquires through training some detailed knowledge of anatomy. Among the first Englishmen to take serious interest in jujutsu and introduce it to other nations were Captain Francis (or Frank) Brinkley (1841-1912), Francis James Norman (1855-1926), Edward William Barton-Wright (1861-1951) and Earnest John Harrison (1873-1961). All four British jujutsu pioneers were scholars, especially Brinkley and E.J. Harrison who wrote not only on jujutsu but also quite extensively on other aspects of Japanese culture, which included architecture, language study, art, ceramics, history, manners, customs and so forth.

Francis Brinkley was an Anglo-Irish newspaper proprietor who resided in Meiji-period Japan for over 40 years. He was moreover, for varying stints, a diplomat, educator, prolific writer and translator. In 1867, Brinkley first went to Japan. Later, he and his son, Jack Ronald Brinkley (1887-1964), contributed greatly to education and to Japanese culture. Son Jack, by the way, joined the Budokwai in later years and met Gunji Koizumi (1885-1965) and served the British military in India where following World War II he met Trevor Pryce Leggett (1914-2000).

Francis Brinkley was an Anglo-Irish newspaper proprietor who resided in Meiji-period Japan for over 40 years. He was moreover, for varying stints, a diplomat, educator, prolific writer and translator. In 1867, Brinkley first went to Japan. Later, he and his son, Jack Ronald Brinkley (1887-1964), contributed greatly to education and to Japanese culture. Son Jack, by the way, joined the Budokwai in later years and met Gunji Koizumi (1885-1965) and served the British military in India where following World War II he met Trevor Pryce Leggett (1914-2000).

Francis Brinkley was born at Leinster, Ireland, in 1841. His paternal grandfather, John Brinkley, was a bishop and the first Royal Astronomer of Ireland, while his maternal grandfather, Richard Graves, was a Senior Fellow of Trinity College and Dean of Ardagh, County Longford. Brinkley studied at the Royal School Dunganon and at Trinity College, Dublin, and was reportedly at the top of his class in mathematics and classical studies. After graduation, he entered the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, and earned an appointment as an artillery officer. Brinkley was posted to Hong Kong where he was engaged as adjutant to the British Hong Kong Governor General, Sir Richard Graves MacDonnell, who was a relative. In 1866 on his way to Hong Kong, he had occasion to visit Nagasaki, Japan, where he happened to witness a duel between two samurai. The victor covered his slain adversary with his ‘haori’ coat and then knelt beside the corpse in pray. Brinkley was apparently so impressed by this gesture, that it motivated him to make Japan his permanent home. In 1867 therefore, he returned to Japan where he remained for the rest of his life.

Attached to the British-Japanese Legation in 1867, and still an officer in the Royal Artillery, he was assigned assistant military attaché to the Japanese Embassy. In 1871, however, he resigned his commission and took up the post of foreign advisor to the new Meiji government. He later taught artillery science for five years at the new Imperial Japanese Navy’s Gunnery School at Etajima, Hiroshima Prefecture. In 1878 he was invited to teach mathematics at the Imperial College of Engineering which afterward became part of Tokyo University. He gave instruction there for two and a half years. Brinkley studied and apparently quickly mastered the Japanese language.

During the Meiji period, there were three English language newspapers in circulation, all of which were published in Yokohama. One was the Japan Mail (later to merge with The Japan Times), which Brinkley owned and for which he was chief editor between 1881 and 1912. His Japan Mail was widely read in the Far East. It was mainly by means of his newspaper that he was able to help introduce jujutsu and other aspects of Japanese culture internationally, support both the Anglo-Japanese Treaty, and the revision of the unequal treaties concluded between Japan and several other nations.

Francis Brinkley produced his famous 12-volume work China and Japan (J.B. Millet Company, Boston, 1902); eight volumes of which are focused on Japan and four on China. Volume three contains pages mentioning jujutsu. He says, “The science starts from the mathematical principle that the stability of a body is destroyed as soon as the vertical line passing through its centre of gravity falls outside its base. To achieve disturbance of equilibrium in accordance with that principle, the jujutsu player may throw himself on the ground by way of preliminary to throwing his opponent. In fact, to know how to fall is as essential a part of this science as to know how to throw. Checking, disabling by blows delivered in special parts of the body, paralyzing an opponent’s limb by applying a ‘breaking moment’ to it, all these are branches of the science, but it has its root in making an enemy undo himself by his own strength.”

While there is no indication that he actually practiced jujutsu, he obviously spent considerable time analyzing the techniques and theory in a capable manner. He describes how jujutsu shared the decadence that befell all the military arts of the samurai with the onset of the Meiji Restoration and how an eminent educationist, Professor Jigoro Kano, revived it, teaching gratuitously at two large institutions.

Towards the end of his life, Brinkley wrote popular English language text books for Japanese students. He, together with Fumio Nanjo and Yukichika Iwasaki, compiled an English-Japanese dictionary. He also wrote A History of the Japanese People that was published posthumously by The Times in 1915. This book dealt mainly with fine arts and literature from the origins of the Japanese people through to the latter half of the Meiji period.

In 1912 Emperor Meiji died. Both General Maresuke Nogi and his wife together followed him by committing ritual suicide (seppuku) on the day of the emperor’s funeral. Brinkley’s last report was, “On General Maresuke Nogi,” which was sent for publication in The Times of London. One month later Brinkley himself died at the age of 71. His funeral was attended by many dignitaries, including Speaker of the House of Peers, Iesato Tokugawa, the Minister of the Navy, Makoto Saito, and Foreign Minister Yasuya, which clearly indicates how much respect the Japanese hierarchy, had for him.

The next of our British jujutsu pioneers of interest is another Francis, this time Francis James Norman (1855-1926) a military man in the 11th Hussars and an avid scholar of Japanese martial arts who was born in British India at Mooltan in the Punjab (this city name is now spelt Multan and is in Pakistan) Norman therefore spoke Urdu as well as English. He had great interest not only in jujutsu, but more so in kenjutsu and later kendo. He lived in Japan from 1888 to around 1902 and later published The Fighting Man of Japan: the Training and Exercises of the Samurai (Archibald Constable & Co., London, 1905). His book contains chapters on jujutsu, sumo, kenjutsu, Japan’s military history, and on the education of military and naval officers and other insights into Japanese society. Norman was apparently urged to write his book at the request of The Japanese School of Jujutsu in London to assist Yukio Tani and Taro Miyake in popularizing jujutsu in the UK. Norman was highly regarded as one of the foremost and keenest kenjutsu exponents of his time. Judo expert E.J. Harrison who lived in Japan at about the same time as Norman said this of him: ‘Perhaps the only foreigner who ever took up kenjutsu seriously is F. J. Norman, late of the Indian Army, a cavalry officer, and expert in both rapier and saber play. Norman was for some years engaged as a teacher of English at the Etajima Naval College, and while there devoted his attention to the Japanese style to such good purpose that he speedily won an enviable reputation among the Japanese, and engaged in many a hard-fought encounter. Some other foreigners have practiced, and doubtless do practice kenjutsu for the sake of exercise, but I am not aware that any one of them has won distinction in Japanese eyes.’ (E. J. Harrison, The Fighting Spirit of Japan, T. Fisher Unwin, 1913)

The next of our British jujutsu pioneers of interest is another Francis, this time Francis James Norman (1855-1926) a military man in the 11th Hussars and an avid scholar of Japanese martial arts who was born in British India at Mooltan in the Punjab (this city name is now spelt Multan and is in Pakistan) Norman therefore spoke Urdu as well as English. He had great interest not only in jujutsu, but more so in kenjutsu and later kendo. He lived in Japan from 1888 to around 1902 and later published The Fighting Man of Japan: the Training and Exercises of the Samurai (Archibald Constable & Co., London, 1905). His book contains chapters on jujutsu, sumo, kenjutsu, Japan’s military history, and on the education of military and naval officers and other insights into Japanese society. Norman was apparently urged to write his book at the request of The Japanese School of Jujutsu in London to assist Yukio Tani and Taro Miyake in popularizing jujutsu in the UK. Norman was highly regarded as one of the foremost and keenest kenjutsu exponents of his time. Judo expert E.J. Harrison who lived in Japan at about the same time as Norman said this of him: ‘Perhaps the only foreigner who ever took up kenjutsu seriously is F. J. Norman, late of the Indian Army, a cavalry officer, and expert in both rapier and saber play. Norman was for some years engaged as a teacher of English at the Etajima Naval College, and while there devoted his attention to the Japanese style to such good purpose that he speedily won an enviable reputation among the Japanese, and engaged in many a hard-fought encounter. Some other foreigners have practiced, and doubtless do practice kenjutsu for the sake of exercise, but I am not aware that any one of them has won distinction in Japanese eyes.’ (E. J. Harrison, The Fighting Spirit of Japan, T. Fisher Unwin, 1913)

Norman was evidently therefore the only non-Japanese kenjutsuka who trained diligently at that far off time. Unlike Western fencing, what seems to have intrigued him most was the educational and spiritual potential which he believed that one could cultivate by training in the budo arts. Norman mentioned the following in his book: ‘Much advantage might accrue to his native country from the introduction of exercises so admirably calculated to improve the physique and also the morale of its youth and manhood.’ One striking difference between British culture and Japanese soon became apparent to Norman. In Japanese martial arts, there is no such thing as ‘fair play’. For instance, if a man happened to drop his weapon during a tussle, his adversary would immediately take full advantage of the situation and deliver the decisive blow, a clear indication of the variance between sportsmanship and warfare. Thus, the Japanese had firm belief in ‘all is fair in love and war’ and ‘the end justifies the means’.

In 1898 a British civil engineer, Edward William Barton-Wright (1861-1951), returned to England after three years spent in Japan working on the construction of a railway. He had become aware of jujutsu, trained, and took great interest in the art becoming our next British jujutsu pioneers. In an effort to introduce jujutsu to the British public, he combined it with the best elements of a range of other fighting systems including boxing, wrestling, fencing and savate styles into a unified whole that he named Bartitsu, a new art of self defence. This name was a portmanteau of his surname and that of ‘itsu’. In order to boost the appeal of this new art he gave public demonstrations, interviews, and wrote a series of magazine articles that appeared in Pearson’s Magazine between 1899 and 1901. He later opened his own school naming it ‘Bartitsu Academy of Arms and Physical Culture’, which was located in Soho, London, and became known informally as the Bartitsu Club. To boost recognition further, he contacted Professor Jigoro Kano (1860-1938), founder of the Tokyo Kodokan, and requested his assistance in finding jujutsu experts who would be willing to come to Britain to teach. Although Yukio Tani became the most popular and successful of the jujutsu experts, Kano was apparently reluctant to recommend him because he thought that his knowledge of English was inadequate to the task. Also, of note, many of the first classes of British students keen to learn jujutsu were in fact young women. This was the time of the suffragettes, who were often attacked by men and sometimes by police officers when they were campaigning for women to have the right to vote.

In 1898 a British civil engineer, Edward William Barton-Wright (1861-1951), returned to England after three years spent in Japan working on the construction of a railway. He had become aware of jujutsu, trained, and took great interest in the art becoming our next British jujutsu pioneers. In an effort to introduce jujutsu to the British public, he combined it with the best elements of a range of other fighting systems including boxing, wrestling, fencing and savate styles into a unified whole that he named Bartitsu, a new art of self defence. This name was a portmanteau of his surname and that of ‘itsu’. In order to boost the appeal of this new art he gave public demonstrations, interviews, and wrote a series of magazine articles that appeared in Pearson’s Magazine between 1899 and 1901. He later opened his own school naming it ‘Bartitsu Academy of Arms and Physical Culture’, which was located in Soho, London, and became known informally as the Bartitsu Club. To boost recognition further, he contacted Professor Jigoro Kano (1860-1938), founder of the Tokyo Kodokan, and requested his assistance in finding jujutsu experts who would be willing to come to Britain to teach. Although Yukio Tani became the most popular and successful of the jujutsu experts, Kano was apparently reluctant to recommend him because he thought that his knowledge of English was inadequate to the task. Also, of note, many of the first classes of British students keen to learn jujutsu were in fact young women. This was the time of the suffragettes, who were often attacked by men and sometimes by police officers when they were campaigning for women to have the right to vote.

In 1901, three jujutsuka, Seizo Yamamoto, brothers Kaneo Tani and Yukio Tani (1881-1950) arrived in the UK. After a short stay both Yamamoto and Kaneo Tani left and returned to Japan. Yukio Tani, however, remained and shortly thereafter he was joined by the skillful Sadakazu Uyenishi. Besides teaching well-to-do Londoners, they also began successful careers as music hall entertainers by issuing challenges for prize money to opponents of any size and weight. Tani allowed his opponents freedom to use all techniques that they wished. His only insistence was that they wear a jacket. This was, of course, the one advantage that he needed for his many opponents be they wrestlers or boxers were invariably much larger than he. In addition to jujutsu, the Bartitsu Club became the headquarters for a group of fencing exponents led by a Captain Alfred Hutton. Capt. Hutton taught fencing techniques mainly to actors, who sometimes needed to perform realistic combat fencing for use in drama scenes.

Barton-Wright encouraged members of the Bartitsu Club to study a range of the major hand-to-hand combat styles taught at the Club. The purpose being to master not just one but each style well enough so that they could be used if needed in self defense. This process was similar to the modern concept of cross-training. He stressed the use of a walking stick as the first mode of defence; followed if need be by the all-in grappling style of aggressive combat in order to defend oneself.

Despite his great enthusiasm, however, Barton-Wright seems to have been a mediocre businessman for by March 1902, the Bartitsu Club ceased teaching martial arts for some reason. One of his instructors, William Herbert Garrud, the gymnast, boxer, wrestler and author of The Complete Jujutsuan published in 1914, and husband of Edith Margaret Garrud (1872-1971) suggested that both the enrollment and the tuition fees had been too high. Or perhaps, Barton-Wright had simply overestimated the number of wealthy Londoners who shared his intense interest in such exotic self-defence systems. Also, at this juncture rumour had it that money issues had arisen between Barton-Wright and his instructors who subsequently parted company from him. In 1904 therefore, Yukio Tani and Taro Miyake set up their own dojo at 305, Oxford St., London, and named it, The Japanese School of Jujutsu. They published a book, The Game of Jujutsu in 1906, the same year that they closed down their school. Other instructors also left Barton-Wright. The Swiss wrestler Armand Cherpillod returned to Switzerland and introduced jujutsu to Germany and other European countries. The French La savate and fencing expert Pierre Vigny also left and opened his own school.

Nevertheless, displays of jujutsu prize fighting remained popular entertainment at music halls all over Britain, especially so between 1900 and the late 1920s. Barton-Wright, however, chose to embark on a new career, that of a physical therapist in which he specialized in innovative forms of heat, light and radiation treatment for patients suffering from a variety of aliments.

The name Bartitsu might have been almost completely forgotten if it were not for a reference to it made by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in one of his popular Sherlock Homes mystery stories. For in 1903, Conan Doyle had revived Holmes for a further story, The Adventure of the Empty House, in which Holmes explained his victory over arch enemy professor Moriarty in their struggle at Reichenbach Falls by the use of ‘baritsu’ which did not exist outside the pages of the English editions of The Adventure of the Empty House and in a 1901 London Times newspaper report entitled ‘Japanese Wrestling at the Tivoli’ which covered a Bartitsu demonstration in London but the name was misspelled as “Bartisu”. Perhaps Conan Doyle took this misspelled word from The Times and used it in his novel.

Barton-Wright spent the remainder of his career as a physical therapist focused on sometimes controversial forms of therapy. He continued to use the name Bartitsu, however, with reference to his therapeutic businesses. In 1950 he was interviewed by Gunji Koizumi for an article that appeared in the Budokwai newsletter, and later that year he was presented to the audience at a Budokwai gathering in London.

Barton-Wright was obviously a man ahead of his time. He was among the first Europeans known to have studied Japanese martial arts, and was almost certainly the first to have them taught in Europe. He was therefore a pioneering promoter of mixed martial arts or MMA contests, in which experts in differing fighting styles compete under common rules. He died in London, UK, in 1951 at the advanced age of 90 years, and according to Richard Bowen, he was buried in a pauper’s grave.

Finally, a man who had an immensely varied career was that of the intrepid journalist Earnest John Harrison who was born in Manchester, UK, on 22, August 1873. His parents separated shortly after his birth for he recalled that he vaguely remembered his father but had no recollection of his mother. He was raised by an uncle, J.S.R. Phillips, who became nationally known as the editor of The Yorkshire Post newspaper in Leeds. Harrison seems to have taken after his father who was athletically inclined and ranked the best boxer in the Manchester Athenaeum Club. As a boy he became an avid wrestler, especially favouring the Cumberland and catch-as–catch–can styles, in which all holds are permitted. As did most children in those days, he seems to have had little formal education for he had to go to work at the age of fifteen. He was employed at the Manchester Reference Library and while there he became an admirer of the works of Shakespeare and Thomas Macaulay. This experience no doubt helped him greatly in his future career as a journalist. He became an expert stenographer and typist and studied French. At the age of 19 he left England for New Westminster, British Columbia, Canada. He became a newspaper reporter for the Vancouver News-Advertiser and in 1896 he had the good fortune to interview Mark Twain in Vancouver. His report of the famed man was subsequently telegraphed throughout the USA. While in Canada, he continued with his wrestling and was coached by a well-known lightweight named Jack Stewart. He left Vancouver for San Francisco and got a job on the San Francisco Call. Just before a major earthquake struck California in 1897, his ship departed for Japan.

Finally, a man who had an immensely varied career was that of the intrepid journalist Earnest John Harrison who was born in Manchester, UK, on 22, August 1873. His parents separated shortly after his birth for he recalled that he vaguely remembered his father but had no recollection of his mother. He was raised by an uncle, J.S.R. Phillips, who became nationally known as the editor of The Yorkshire Post newspaper in Leeds. Harrison seems to have taken after his father who was athletically inclined and ranked the best boxer in the Manchester Athenaeum Club. As a boy he became an avid wrestler, especially favouring the Cumberland and catch-as–catch–can styles, in which all holds are permitted. As did most children in those days, he seems to have had little formal education for he had to go to work at the age of fifteen. He was employed at the Manchester Reference Library and while there he became an admirer of the works of Shakespeare and Thomas Macaulay. This experience no doubt helped him greatly in his future career as a journalist. He became an expert stenographer and typist and studied French. At the age of 19 he left England for New Westminster, British Columbia, Canada. He became a newspaper reporter for the Vancouver News-Advertiser and in 1896 he had the good fortune to interview Mark Twain in Vancouver. His report of the famed man was subsequently telegraphed throughout the USA. While in Canada, he continued with his wrestling and was coached by a well-known lightweight named Jack Stewart. He left Vancouver for San Francisco and got a job on the San Francisco Call. Just before a major earthquake struck California in 1897, his ship departed for Japan.

Arriving in Yokohama in 1897, he gained employment as the sole reporter and news editor for Brinkley’s Japan Herald and at the age of 23 began training in Tenjin Shinyo-ryu jujutsu. Later, moving to Tokyo, he joined Jigoro Kano’s Kodokan and trained almost daily in Kodokan judo. In 1911 he became the first foreign-born person to achieve a black belt shodan grade. The following year he published The Fighting Spirit of Japan that was one of the early English-language books to describe both Japanese martial arts and aspects of Japanese culture from the perspective of a non-Japanese.

During the First World War (1914-1918) Harrison joined the military and was chosen as an officer in the Chinese Labour Corps from December 1917 to July 1918. He was next transferred to Military Intelligence on the strength of his knowledge of Russian and was sent to Archangel with the Allied Expeditionary Force. After demobilization in 1919 with the rank of Lieutenant he was appointed to a post as secretary on the British Mission to the Baltic Provinces, serving in Riga, Latvia, Reval and Estonia, and afterward designated Vice-Consul in Lithuania where he saw considerable fighting in both Estonia and Lithuania. He left Lithuania in 1921 to take up a position as press secretary for the Lithuanian legation in London where he worked until 1940.

During the Second World War he served for four years in the Postal and Telegraph Censorship as an Examiner for Russian, Lithuanian and Polish languages. Following the end of the war, he and his second wife Rene (his first wife was Cicely Ross, the sister of fellow judoka Dr. Arthur John Ross of Australia) and their daughter Mrs. Aldona Collins had financial difficulties. The fall of Lithuania to Soviet forces at the end of World War II meant the cancellation of his Lithuanian pension that was due to him after some 20 years’ service. This was a cruel blow, which left him and his wife in greatly reduced circumstances. They made their livelihood, as best they could, by running a guesthouse. Harrison, then aged 67, struggled to augment his somewhat meager income by writing. He also found it necessary to keep up his knowledge of Japanese, Lithuanian, Russian, Polish, French, plus some German and Spanish. T.P. Leggett once remarked that Harrison, an exercise buff, was the toughest man he had ever met. Even late in life he would rise at 7a.m. sharp, shave, bathe in cold water, and go through half-an-hour’s physical exercise, most mornings doing as he recalled 20 or more push ups.

Following the end of World War II Harrison continued to participate in judo practice at the Budokwai where Gunji Koizumi eventually awarded him 4th dan on 7 January 1956 at age 82. Most of his books from 1921 to 1940 were centered on Lithuanian affairs. Similar to the above-mentioned scholars, E.J. Harrison was an accomplished linguist, journalist and translator. He published some 30 books including works on Lithuanian topics, Russia, physical training, karate, wrestling, jujutsu as well as eight books on judo. He died in London on 23, April 1961 at the advanced age of 87.

What struck me most while researching the achievements of these extraordinarily adventurous and energetic British jujutsu pioneers was that they obviously felt duty-bound to introduce not only jujutsu, the art of war, but also the salient arts of peace in Japanese culture for the enlightenment of the international community. For this reason alone they deserve some recognition.

Finally, a quote from a distinguished multi-talented philosopher, mathematician, writer, political activist and Nobel Prize winner:

Love is wise, hatred is foolish.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970)

References:

The Father of Judo, B.N. Watson, Kodansha International, 2000, 2012

Judo Memoirs of Jigoro Kano, B.N. Watson, Trafford Publishing, 2008, 2014

The Fighting Man of Japan F.J.Norman, Introduction A. Bennett, Bunkasha International, 2013

A Résumé of My Chequered Career, E.J. Harrison, Journal of Combative Sport, 1999

Saving Japan’s Martial Arts, C. M. Clarke, Clarke’s Canyon Press, 2011

100 Years of Judo in Great Britain, Vol. 1, Richard Bowen, IndePenPress, 2011

IL Padre Del Judo, (Italian) B.N. Watson, Edizioni Mediterranee, 2005

Memorias de Jigoro Kano, (Portuguese) B.N. Watson, Editora Cultrix, 2011