By Ben Westhoff ~ Sensei Elliot Freeman is surrounded by strip-club bouncers, who are sitting Indian-style in a semicircle around him. A smiling Micheal Ocello, the bouncers’ boss, looks particularly Buddha-like. The men have gathered to learn how to disarm and demobilize the drunken, belligerent, sexually frustrated men they encounter on a nightly basis at clubs like Diamond Cabaret and PT’s, without actually harming them.

“We’re not a martial art,” barks Freeman, “we’re a martial —”

“— science!” yell the men, for whom Ocello has shelled out about 500 bucks apiece to enroll in this intensive, weeklong course, entitled Defensive Tactics Technologies. An offshoot of the Japanese art of aikido, the method focuses on using your opponent’s own strength to neutralize him.

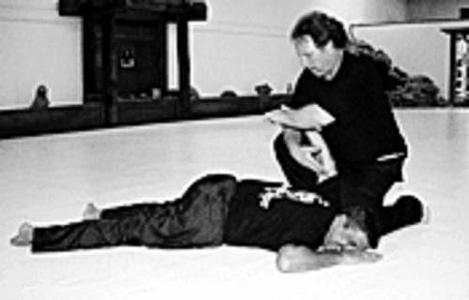

“We’re not concerned with religion,” Freeman goes on. “We’re just concerned with surviving to go home to our children at night.” At his signal, one of the thick-necked bouncers — who looks as though he’d fit right in as a Sopranos extra — stands and then lunges for Freeman’s neck. The instructor deflects him, pivots and within a second has him pinned against the mat.

“A five-year-old girl could do this!” the instructor exclaims.

A New York city native who moved to the St. Louis area more than a dozen years ago, Freeman has been teaching classes at his Maplewood center, Three Rivers Aikido, almost ever since. His belly, mustache and slight lisp are perhaps not befitting of a martial-arts master, but his association to Steven Seagal is. Freeman perfected his craft via the instruction of the ponytailed movie star, considered a foremost non-Japanese aikido expert. Freeman says he met Seagal when he attended an aikido seminar at the actor’s Montana ranch in 1991, which led to an ongoing mentorship. “He’s always been known by his students as a generous, masterful teacher,” the pupil says adoringly.

The strip-club employees have come to learn techniques that will not only spare themselves but their assailants as well. Wary of lawsuits brought by manhandled patrons, Ocello sought a nonviolent approach to handling the out-of-hand.

“Something happens, and there ends up being a fight, and you put your hands on people, and you can get sued,” explains Ocello, president of International Entertainment Consultants, Inc., and one of the nation’s foremost nudie-bar tycoons. “There have been cases where people have actually been killed — not in our nightclubs, but in others — because a fight broke out.”

Ocello says he tried taking his men through other tactics programs but wasn’t satisfied until he found Freeman.

“After going through it, now I think it’s awesome,” the mogul marvels, adding that he plans eventually to have all his male employees at all of his clubs nationwide enroll in similar courses. “It’s something that everybody in the industry ought to consider applying.”

Other industries, too, it would seem.

David Camp, who chairs the criminal-justice department at Culver-Stockton College, invited Freeman to the Stockton, Missouri, school to teach an annual seminar tailored for criminal-justice majors.

“I wanted my students to see that there was an option against the basic hitting, punching and hurting people,” says Camp, who notes that nonviolent disarmament tactics are preferable in an era of videotaped police brutality. “From my experience, it’s the best. I can guarantee you that every single tactic I’ve seen Elliot use works every time.”

Richmond Heights police officer Scott Stebelman says he has used Freeman’s tactics in his everyday police work, with great success.

“When you’re up close and personal with someone — say on a traffic stop — a lot of times you don’t have time to deploy your pepper spray, baton, Taser, or what have you,” says Stebelman, who has been studying with the Maplewood sensei on and off since 1994. “All you have is your empty-hand control, your techniques. What you learn from Elliot is the ability to redirect somebody’s forward momentum. It gets them off their line of attack, and it gives you time to fall back and go to an alternate tactic or weapon. Why kill somebody? Why use that deadly-force option if you can use something a little less violent, but effective?”

Stebelman, who graduated from the St. Louis County and Municipal Police Academy in 1993, says he wishes his instructors had incorporated more nonviolent techniques into the curriculum. “From what I remember, in the academy it was simple joint locks, or straight arm-bar takedowns. It really limited you in your options.”

Sergeant Steve Hampton, who supervises basic training at the police academy, says the school has no plans to implement martial arts into its curriculum. The academy already teaches a nonviolent method to control assailants, Hampton points out. “PPCT [Pressure Point Control Tactics] is the training system that we use. It’s a nationally recognized, legally defensible system that has been in place for years. All these other systems now that are being used have never stood the test of time through the court system.”

The trouble with PPCT, counters Camp, is that it’s ineffective.

“PPCT uses the idea of pain to control an offender,” says the criminal-justice professor. “It’s widespread, and I’ve seen it fail. The problem is that if the person is under the influence of drugs or alcohol, pain’s not going to work. Elliot’s system is using mechanical control, manipulating the wrist and elbow joints. It doesn’t matter if it hurts or not — you still can’t work against it.”

Hampton points to pepper spray and Tasers as other nonviolent methods the police academy advocates. The Taser, an electric stun gun, is generally considered a nonlethal alternative to bullets. But a New York Times story last month called the weapon’s safety record into question, pointing out that the Taser has been subjected to virtually no scientific testing and noting that six people died after being shocked by Tasers during the month of June alone.

The company that manufactures the weapon, Taser International, defends its product. But some area cops, like Columbia, Illinois, officer Justin Barlow, have their doubts.

“Tasers are pretty easy to use, but there’s a lot of people saying, ‘Well, what if you used it on somebody that has a heart condition?'” Barlow himself has been studying with Freeman for the past year or so. “I think that Tasers are great, but as far as trying to control a situation from exploding, I would rather use this.”

Steven Jimerfield, a retired Alaska state trooper who as a member of the American Society for Law Enforcement Training helps disseminate information about the latest self-defense tactics, says aikido and its offshoots aren’t in vogue at training facilities nationwide. “Most law-enforcement officers do not like the martial arts, but everything we teach in self-defense comes from the martial arts,” Jimerfield allows. “I’m not a real proponent of aikido,” he adds. “Most of what I’ve seen of aikido doesn’t work on the street. It requires too much space and room to work, so in a crowded space it’s not going to be very effective. I love aikido — don’t get me wrong, it’s a great martial art — but to be very good at it requires many, many years of training at a high skill level.”

David Camp, meanwhile, is such a strong believer that he signed up his nine-year-old daughter for Freeman’s training.

“She can put grown men on the ground,” he says. “And she has. We have football players in my class here, and she comes and trains with them, and they’re like: ‘Hey, get her off of me!'”

By Ben Westhoff – River Front Times (August 4, 2004)