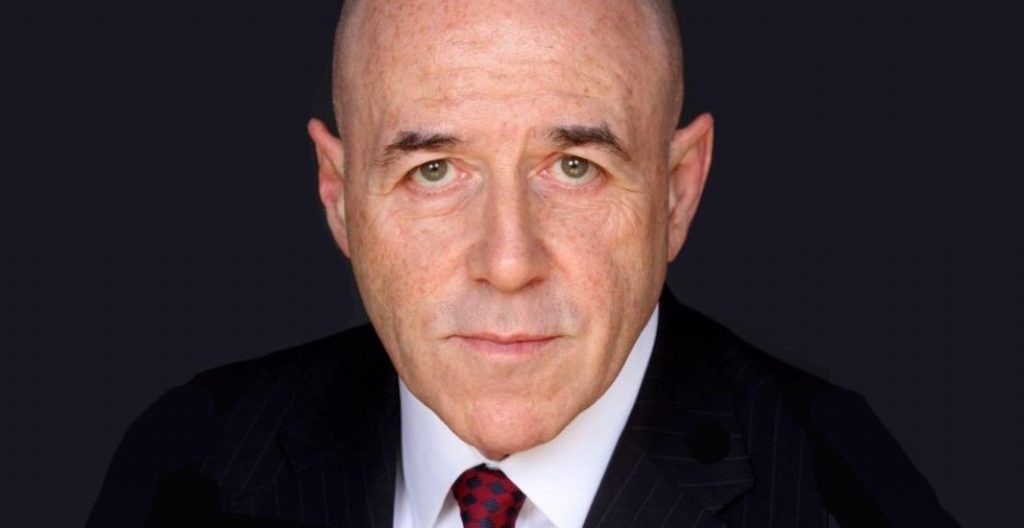

Stephen Oliver: Master Bernard Kerik has been training in martial arts since 1969 and he has accomplished an awful lot in martial arts as well as in his career in many, many, many ways. And without giving you a full recap, as you know, former Commissioner in New York City Police Department, former Interim Minister of Iraq, to help rebuild their police force, and close confidant of Mayor Guilliani in the crisis of 9/11 and the reconstruction of that. And I’d like everybody to stand up. Welcome and bow to Master Kerik.

Stephen Oliver: Master Bernard Kerik has been training in martial arts since 1969 and he has accomplished an awful lot in martial arts as well as in his career in many, many, many ways. And without giving you a full recap, as you know, former Commissioner in New York City Police Department, former Interim Minister of Iraq, to help rebuild their police force, and close confidant of Mayor Guilliani in the crisis of 9/11 and the reconstruction of that. And I’d like everybody to stand up. Welcome and bow to Master Kerik.

Bernard Kerik: First, I want to say thank you to Master Smith and Master Oliver, for the honors they gave me last evening. (Bernard Kerik was promoted to Master Kerik, 5th degree Black Belt by Master Jeff Smith and Master Stephen Oliver).

I also wanted to say thank you for the invitation to be here.

How many people were here last night? You’re going to have to hear some of this again.

How many people were with me in the other room? Okay. So I’ve got to repeat everything I said yesterday, in one form or another. So you may fall asleep. At the rate you’re going, you may fall asleep anyway.

A couple things I want to start with. Master Smith, Jeff Smith, when I started in the martial arts in 1969, I was 14 years old. I was intrigued by the arts. I grew up in an environment that was not such a nice one. I went to a high school that was not such a nice one.

How many people in this room have seen the movie “Lean On Me,” Joe Clark, Eastside High School, walking around with a baseball hat and a bull horn? I was in that school long before Joe Clark. Before Joe Clark got to clean it up, I was one of the students.

So it wasn’t really a learning environment and I tried to focus on other things. One of the principle things I started to focus on was the martial arts.

In 1969, when I began, and Master Oliver began, we trained as hard as we could. We tried to follow the right people, the right instructors. I had some phenomenal instructors in New Jersey and New York City. I ultimately went to Korea. I trained in Korea for about a year and a half. I’ve been back there several times since.

But when I was 14 and this all began, I used to read every month, religiously, read Black Belt magazine, Karate Illustrated, anything that had to do with the arts.

And ironically, that guy’s picture was on the cover every time I picked up the magazine. World champion, world kickboxing champion, world point contact fighter champion, the best of the best of the best. Jeff Smith was and is one of the best in the entire world.

And ironically, I never got to meet him. I got to see him fight. I watched him in person. I watched him on television, but I never got to meet him until after September 11th. And that was one of the biggest honors in my lifetime, because he was somebody that I admired, I watched. I watched his career grow. I watched him grow. And it was a great honor to meet him and to ultimately become very good friends with him.

Through Master Smith, I met Master Oliver. I have to tell you, I’ve been involved in the arts since 1969, and I’ve trained with some of the biggest names in the world.

When I was in Korea, I trained with the world tae kwon do demonstration team. I trained in Chuncheon, which is the world tae kwon do headquarters. I trained with some of the best.

But I’ve learned a lot about instructors in this country, in Korea, and around the world. And that is everybody has an agenda, one way or another. Not many people in the world of martial arts, especially in the commercialized world of martial arts, where we people have opened schools and businesses and created a livelihood for themselves, not everybody takes the traditions that were created in the arts and maintains them.

But I can tell you that what you’re going through between yesterday, today and tomorrow, in my opinion – and Master Smith and I talked about this last night – is probably some of the most aggressive training, aggressive testing and aggressive teaching in the arts that I’ve ever seen.

And I’ve been all over.

So I want to commend Master Oliver for his commercial awareness, for what he has done for the arts, but more importantly what he’s done for you.

For the black belts that are testing, this is a real test, an extremely difficult test. But you can guarantee, when you walk away with your first degree or more, you can guarantee it was well- deserved, it was well-earned. Nobody gave you just a piece of paper. You didn’t buy it and pay for it. This is something that was deserved, that you worked extremely hard for, and you should be commended for being here.

As I took some of the photos outside and I look at the faces of some of the people that stood there for photos, they’re tired. How many people aren’t tired? Not too many.

I’ve got to tell you, me and Master Smith, we’re exhausted, and we haven’t done anything. Really, we’re just here to visit.

So I give you an enormous amount of credit for what you’re doing. And I really have to commend Steve Oliver for what he has done for the arts and for you, the students in his schools around the country.

Nobody does this. Believe me when I tell you, nobody does this. Nobody has the following he has. Nobody has the camaraderie he has. Nobody is insane enough to give a test for 48 hours.

But that’s what makes this so great, so good, so real, and something that you all should be extremely proud of.

With that, I think we should give Master Oliver a big hand.

For the next few minutes, I want to talk to all of you a little bit about me and where I came from, and how I have gotten to where I am today. And maybe help you learn a few lessons in life that will help you.

Some of the sort of executives that I spoke to yesterday, you may have heard some of this already, too bad. You have to hear it again. But for the rest of you, I’ll try to tone it down and speed it up a little bit. But if you take anything away from anything that I’m going to stand up here and say today, I want you to listen, pay attention, and take away a few things.

One, you are receiving some of the best training in the country, by some of the best professionals. And you have an opportunity to do things in life that many other people do not, because you are learning things that other people don’t learn.

And it’s been such a pleasure to walk through this resort over the last few days, get on an elevator with a 10-year-old child who doesn’t know me, doesn’t know who I am, get on that elevator, they get on and I say, “Good morning,” and they say, “Good morning, sir! Good afternoon, sir!” I hold the door for them, they say, “Thank you, sir,” 10 years old, 9 years old, 11 years old.

It’s a great pleasure to get to witness and see and feel that. Because in the environment we live today, respect, integrity, honor is not always taught in a household. But it’s something you’re learning in your classes from day one, and it’s something you’re going to have for the rest of your life.

I received my 1st degree black belt when I was 16, almost 17, and I’ve been in the arts ever since. And I’ve had some tremendous jobs in my lifetime.

I ran one of the biggest jail and prison systems in the country, Riker’s Island. I ran the New York City Police Department, 55,000 people and a $3.2-billion budget. I’ve worked for Mayor Guilliani, I’ve worked for President Bush.

You know what? Still, to this day, I walk into meetings and I hold the door open for someone, even in the positions I’m holding, and somebody will walk in right behind me and not say thank you, forget about the sir. They have no respect. They don’t understand it. And it makes a tremendous difference.

I have a 20-year-old son, and we will go somewhere, when I’m with my son, and someone will say something to me and I’ll say, “Good morning, sir! Good afternoon, sir!” My son will say,

“Who was that?” “I don’t know. I don’t know who it is.” “But you called him sir.” “That’s okay. It’s okay thing to do, because it’s a sign of respect.”

And people notice, especially for the young kids in this room today, people notice. Every time you say that, every time you say thank you, every time you say sir, every time you show someone a sign of respect, particularly at the ages you are, people notice. And they instantly have a different perspective of who you are and what you are.

As you grow, and this is for everybody in this room, don’t ever think there’s anything that you can’t do. There’s nothing you can’t do. If you want to do it and it’s in here, it’s in your heart and you feel it, it’s just like getting your black belt. How many people thought that 2 years ago, 3 years ago, 4 years ago, 5, 10, how many people thought you would win, earn, be awarded, be the recipient of a black belt?

I never did when I was younger. I had it here. It was something I wanted. But it was one of those things that was so far distant, I didn’t know if it would ever happen.

For me, when it happened, it wasn’t enough. I wanted the next.

For me, when I became a New York City Detective, I wanted the next step.

Sometimes, when you want the next step and you get it, you look back and say, “I should have stopped at the last one.”

When I became the New York City Police Commissioner, I could remember being appointed, being sworn in, in front of thousands of people on the steps of City Hall in New York. My family, my friends, my colleagues, Mayor Guilliani told me, “You know what? We have 18 months to go. It’s going to be smooth sailing. Crime has to come down a little bit more, but everything’s going to be fine.”

About 3 weeks later, I get a briefing from the Intelligence Division, who tells me that the United Nations is holding their 75th annual summit and there’s going to be 234 heads of state from all over the world coming to New York City.

And I ran over to City Hall and I told the mayor, “I thought you said it was smooth sailing! This is the biggest gathering of heads of state anywhere in the world, at any one time.”

Who’s responsible? I was. Something happens, it’s my fault.

Looking back then, was it difficult? Yes. Was it a challenge? Yes. But it was something that had to be done. I took that step and I did it.

You guys can do the same thing. Whether it’s the police department, whether it’s your school work, whether it’s your high school or college, or whether it’s in the professions and the jobs you have today, be a leader. Don’t be a follower. Be a leader.

For the younger kids in the class today, you’re going to go through school for many, many years. Hopefully, most of those years you will enjoy. And you’re going to get to see other kids that are in your school, kids that they want to be leaders too, but maybe not in the right direction, maybe not doing the right things.

You have an advantage over those kids, all of you. All of you younger girls and guys in this class, you have an advantage because you’ve been taught right from wrong for the last 2, 3, 4, 5 years. You know what’s right and what’s wrong, what’s good and what’s bad. And you also know if you have a question, if you’re not sure, if you don’t think you know the right answer, whether it’s good or bad or right or wrong, you have an advantage. Because that night, when you go to train, you can go to your instructor and you can talk to them in confidence and ask them. You can go home and talk to your parents and ask them.

Your parents, a lot of times, you look at a child in today’s society and you don’t know where their parents’ head is and you don’t know what they’re thinking about. But when I look around this classroom and I look at the kids in here, and I look at what you’re doing today and all of the parents and supporters that are in this room with you, I have absolutely no doubt in my mind that you’ll get the right answer. Maybe some other kids won’t. You will get the right answers.

So if there’s some kids in your school that want to do a certain thing and you think it’s the wrong thing, 1) you do not do it; and 2) you make sure it’s the right thing to do. How do you do that?

You ask your parents, you ask your other kids that you train with, and you talk to your instructors at school and you ask them. They’ll give you the right answer. They’ll tell you which way to go. They’ll tell you the right thing to do.

Make sure you do that. Don’t be a follower, be a leader. Be a leader. This country needs leadership. Our governments need leadership. Our companies need leadership.

For all of the adults in here, I give you a lot of credit. I’ve watched, over the last 24 hours, some of the training, I remember those days. I got my black belt when I was 16, 17 years old, and about a year, year and a half later I went to Korea. And I was in pretty good shape, I thought, when I was here in the US.

And then I went to Korea and I had no conception of what their training was like, what their drills were like. And I got to learn a lot about a work ethic, about dedication, about integrity, and about real, dedicated, hard training.

I give you a lot of credit for what you people are going through, for what you’re going through today.

Take that same work ethic to the field in which you work. Take the leadership traits you learn in here to the field in which you work. And it doesn’t make any difference what the job is. It makes no difference. Whether it’s working in a Home Depot or Wal-Mart, working for IBM or Citi Group, running your own school or a number of schools, no matter what you do for a living, try to be the best. Maintain integrity. Maintain credibility. And try to push what you learn through this mechanism, this learning tool. Try to push it on the others around you. Because nobody knows, particularly the adults in here, you know right from wrong. You know what’s good and bad.

When I was younger, I didn’t have anybody to go to. I didn’t have a mentor or a tutor. And my lifestyle at home was very different. So my guidance, my support mechanism, it all came from my martial arts instructors, one after another, and I had several.

There was a point in my martial arts career I jumped around like a jackrabbit. I would train with somebody for 6 months, I’d see somebody else that I thought was better, I’d go to train with them. One instructor after another, I would take the best of the best from those instructors and I would learn from them. And it put me on the right path.

And the adults will understand this probably a little more than the kids. But in I guess 1985, I became the Warden of the Passaic County Jail in New Jersey. It was a jail that held 1,100 inmates. I was only 30 years old and became the Warden. It’s an extremely big job, one of the top law enforcement officials in the country. And my mother and father came to the swearing-in.

My mother was interviewed by the press. You should never talk to the press. Never. I just want to clarify that. But if you do, you’d better make sure you know what you’re saying.

My mother, she wasn’t press savvy. So the reporter sticks a microphone in my mother’s face and says, “Your son is only 30 years old. He’s the Warden of this jail, one of the top law enforcement positions in the State of New Jersey. What do you think?” My mother’s response? “I always knew he was going to wind up behind bars, but I wasn’t sure what side.”

It is funny now. It wasn’t funny then.

She was absolutely right. There was a time that I could have gone either way. But I became the Warden. Why? Because of the martial arts. Because to those instructors. Because an instructor sat me down one day and said, “Look, you quit school. You shouldn’t have. You have to get a life. You have to get some training. You have to get some internal stability. You need to go in the military.” And I listened and I did.

And between my martial arts training, between going in the military, that was sort of the beginning of my career. One step after another.

And with all of the dedication that I pursued the arts, I pursued my career. I went in the US Army, I became a military police officer. I was on the United States Army Martial Arts Team at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. I got out, I became a cop.

I went to work in Saudi Arabia for the royal family from 1978 to 1980 in the security branches. I left. I came back, I became a cop in North Carolina, became a cop in New Jersey. I went back to Saudi Arabia again, for nearly 2! years, where I ran an investigative division for the royal family’s medical facility.

I came back to New Jersey. I become the Warden of the Passaic County Jail. When you’re the Warden, you’re the Chief. You’re in charge of the whole department. I had 700 people, I had 1,100 inmates, I had a big budget.

I took off the gold shield, I took off the white shirt and the stars. I gave back the car and all or the perks that come with the job, and I went across the George Washington Bridge and I became a New York City Police Officer, a white shield cop. I started from the bottom, after I was on the top. Why? Because it was something I wanted, because it was something

I dreamt about in my younger days. And I did it.

And I could remember everybody telling me, “You have lost your mind! Completely lost your mind!” This was back in 1986. I was making $55,000, $60,000 in 1986, $60,000 a year. I’m in

charge of my own department. And I gave it all up to walk a foot post in Bedford-Stuyvesant, New York, for $23,000 a year, because it was something I wanted to do.

And they were right, at the time. They were absolutely right. They said I was nuts, they were right. I was absolutely out of my mind.

But 14 years later, 14 years later, I got called into the office of Rudy Guilliani, and he told me some very good news. He said, “You are going to be appointed as the Police Commissioner.” So I went from the bottom or the NYPD, 14 years later I was given this shield. It’s 18 karat gold, it has 5 platinum stars. It was created by Tiffany’s in 1897. And the first New York City Police Commissioner’s shield went to somebody you all know. Everybody in this room. His.name was Teddy Roosevelt. Teddy Roosevelt, our President, was the first New York City Police Commissioner.

So when I stood on that podium and I swore to uphold the Constitution and the laws of the State of New York and the city of New York, I could remember looking out in the audience and seeing some of those people that told me 14 years earlier that I was out of my mind. In my mind, as I was taking my oath, I thought, “Who’s laughing now?”

Why? Because it was in here. It was something I wanted to do. And no matter what it is, no matter what it is in your job, in your school, no matter what it is, you can do it. Don’t ever forget that.

I had somebody, very early in my life, when I was in high school, one of my guidance counselors. How many of you young kids, how many of you like your teachers? You like your teachers in school?

How many don’t like their teachers? I don’t know, it’s the same number of hands. It’s a very political group.

Well, I had a teacher that told my mother, in school, I would never amount to anything. “He’s useless. He’s never going to be anything.”

I could remember how much I hated that teacher for saying that, how much I disliked that teacher for saying that. Because I knew in here I was better than that, and I could do something. I didn’t know, at the time, what I could do. But I wanted to do something.

I was 16 years old when that teacher and a guidance counselor basically told my mother I was a vegetable.

Well, here it was sometimes later, that I am being sworn in to run the biggest police department in the free world. Well, that teacher was wrong.

People that tell you, “You can’t do something,” they’re wrong. Don’t ever listen to them. Don’t ever listen to them. You do what you feel is right. You do what’s in your heart. You do what you believe in. And you do it with every bit of passion you can find in your body, and you will achieve that goal, whatever it is.

The last thing I will say, and I’ll close with this, when you get there, it’s going to be rough, it’s going to be hard. Sort of just like getting into this realm or this group that you’re in right now.

You want to get there. You get here, and then you’re going, “Oh my god, what am I getting myself into? 48 hours? This guy’s crazy, 48 hours. Why am I here? What am I doing this for?”

Well, that has happened to me a couple of different times. But there’s never been a worse time than the morning of September 11, 2001. When you think of that day and you remember that day, everybody has a different memory.

I have very vivid memories, very personal memories. Memories of the people that died, memories of the devastation, memories of people that worked for me that never came back.

I can remember coming back to ground zero that night, about 2:00 in the morning. It was really about 2:00 in the morning on the morning of the 12th. Mayor Guilliani told me to go get some sleep, we were going to have to meet again at 5:00 a.m., to meet with some people from the White House and the state police and the state government, Governor Patacki, at the time.

Instead of going back and going to sleep, I went down to ground zero. I wanted to go one more time, because in my mind there was deniability. I just couldn’t believe this had happened. And I can remember walking through the smoke and the debris, and there wasn’t much left of anything, with the exception of metal.

I want you to think about that for a minute. Look around this room. You have carpet, you have these cameras, you have lights, you have poles, you have benches, the chairs, all the things in this room.

Well, think of 2 buildings 110 stories high, that completely pulverized and evaporated. Those metal beams were 1,700 pounds per linear foot. They were the only things left. There was nothing left. And that goes for people, it goes for equipment, it goes for products, resources. It basically disappeared. It was a blast the size of a nuclear blast, almost.

I can remember walking through there that night, going back to my office in the New York City Police Department Headquarters, lying down in my den, in my office, and thinking,

“There is no way we’re ever going to get through this. No way.”

I got up about an hour and a half later. I really didn’t get to sleep. I didn’t sleep right. We have F-16’s flying up and down the Hudson River and up and down the East River, and I could hear them going by. And every time I heard a jet, I would sit up and I would sort of panic with regard to what it was and where it was coming from.

I got up the next morning and, as I left my office, I drove around ground zero and I started to drive back up the East Side drive. There were signs all over of the resilience of this country. Everywhere. What were they? What were the signs?

Attendee: American flags.

Bernard Kerik: That’s right. That’s exactly what it was. Between 2:00 in the morning and 5:00 in the morning, between that afternoon and 5:00 in the morning, the American flag started to rise everywhere. On the back of cars, outside people’s windows, off the tops of buildings, just stuck in poles in the ground alongside of the highways. And I realized then, that the resilience that this government has had over the last 200 years, to build it into the government that we are today, into the country we are today, that resilience is going to get us through this. And it did.

If there’s ever a lesson you can learn, learn that you can make it through everything. If we made it through that, if we can get through Katrina and Rita and some of the other things that have recently happened, you can get through anything. Believe me. Don’t ever think you can’t. No matter who tells you what, no matter what they say, no matter how they say it, take their advice, take their criticism, put it in here. Let it go in here, out here.

Go about your business. Do what you have to do. Do what’s in your heart, and you will succeed. Thank you.

Stephen Oliver: Attention! Bow to Master Kerik and Master Smith. Have a seat. Master Kerik would be happy to do a little bit of question and answer. Adults and parents should be welcome, too. If you have any questions, be welcome to do that. Please come up to the microphone, so everybody can hear and we can have it on tape.

But if anybody has any questions about being Police Commissioner or training in martial arts, or 9/11 or anything else, you’re welcome to ask any of those questions. Anybody have a question? Raise your hand. Come on up. You need to come on up and be miked.

Attendee: Thank you so much for being here. I wanted to know a little bit about your experience in training the police force of Iraq.

Bernard Kerik: My experience in training the police force in Iraq? It was an interesting 4 months. In May of 1903 – 1903, 2003 – in May of 1903, I don’t even think my grandfather was thought about.

Now Master Smith’s happy. Somebody’s finally older than him.

In May of 2003, I received a telephone call from the White House, that they were interested in me talking to members of the Pentagon and others about policing and the possibility of reconstructing the Ministry of Interior in Iraq.

I went down to the Pentagon and I met with the Pentagon officials, and we talked about the interior in a post-Saddam era. And we talked about Iraq in general, what was there, what had been there before.

I won’t get into the details, but one thing led to another and 10, 11 days later, I was in Baghdad.

It was a difficult time. But for me, it was probably one of the most personal and self-rewarding experiences I’d ever had. Because I knew a lot about Iraq, I knew a lot about Saddam Hussein. I knew a lot about the region. I knew a lot about the controversies that people have about the region. And I knew, at the time, what came out of September 11th and how important it was for us to combat terrorism. And to go to Iraq and to get to see Iraq itself, to get to see and meet some of the people, to witness some of the atrocities that had been committed and conducted by Saddam and his regime, and then to know, in my mind, that Saddam was no longer in power and that people wouldn’t have to suffer like they had suffered for 35 years, and I was a part of that, it was extremely rewarding for me to be there.

That being said, it was probably one of the most difficult jobs I had ever had. Imagine tomorrow, imagine this morning, a few hours from now, say 6:00 this afternoon, you have nothing. Every single thing you have is eliminated. You have no house, you have nowhere to live, you have no electricity, you have no water. It’s 120º and you have nothing.

That’s sort of what it was like going to Iraq. Because of the war, because of the atrocities by Saddam, because of the element of war, it was not a good place to be.

We needed electricity. We needed water. And we needed to rebuild.

Right now, you have, all throughout Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, you have the leftover devastation of Katrina and Rita. But you know what? This is the United States. We have resources that we can ship in there tomorrow, today, yesterday. We have people that are trained to do that. We have money that people will give us, whether it’s the government or others, to do that.

In Iraq, that wasn’t the case. We were building and rebuilding. Everybody says, “We’re rebuilding Iraq.” We’re not rebuilding anything. We’re really building Iraq. We reconstructing a government. And it wasn’t an easy task.

In the 4 months I was there, I brought back nearly 40,000 Iraqi police. I stood up 35 police stations in Baghdad. I created the new sort of interim government in the interior. And about 4 or 5 days before I left the country, the new Iraqi Minister of Interior, which I was replacing, was appointed. So when he was appointed, I got to leave.

It was an extremely difficult task. It was eye-opening. It was good to meet and see the Iraqi people, particularly those that were grateful that we had gone there.

This goes for everybody. I am somebody that was on the ground in Iraq, that lived with the people of Iraq. Don’t believe everything you read and see in the press. Please, don’t. Don’t. The reason I say that is because you get a very one-sided picture of what’s happened in that country. Extremely one-sided.

There’s been tremendous progress in the country. Tremendous. Is it perfect? No. But you know what? Japan wasn’t perfect 12 years after we invaded. Neither was Germany. Neither was a bunch of other countries that fell as a result of World Wars. It takes years to rebuild. It takes years to build a democracy.

Sometimes, I don’t know if we use the right word when we say there should be a democracy in Iraq. People think of a democracy, they think of what we have here, the way we live here.

Maybe that’s not what the Iraqis want. But let them create their own constitution, their own government, and have their own freedoms. Freedoms to go to religious services as they want. Freedoms to have women have an education. Freedoms to have their own economic structure.

They should have the right to do that. We have given them that right. It’s not an easy task. There are extreme elements out there that don’t want that to happen. And I’ll sort of make this very simplistic. They don’t want it to happen for one reason: because if we get stability in Iraq and we create another ally in Iraq like we have in Jordan and some of the other Arab nations and Arab countries, you know what? That’s going to spread. It’s going to spread, and people are going to understand that freedom, as Ronald Reagan said in 1967 when he was being inaugurated as Governor in the State of California, “Freedom is one of the best things that people can experience. And if they lose it, they never get it back again.”

It’s not something you inherit, it’s something you have to fight for. That’s what’s being done now in Iraq. It’s not going to be easy, because we have an enemy we’ve never had before.

You look at World War I, World War II, the Korean War, you look at them all, anything we’ve ever done in this country with regard to fighting for our freedom, none of that has anything to do with what’s going on today because the enemy is extremely different. The enemy is so different, we have never fought an enemy like this; an enemy that wants to die for their cause.

And I want to clarify one thing, and this is one of the things I was going to say when I started this conversation, one of the reasons I wanted to go to Iraq and I thought it was a good thing to know and understand the Iraqi people and what was going on there, and knowing what I knew about September 11th, I could remember after September 11th there were several times that we received calls from the Arab community in New York City, where there were biased attacks on Arab-Americas, that there were biased attacks on Muslims, that there were biased attacks on people that they thought were Arabs. They weren’t even Arabs. They may have been Latino or Spanish or whatever.

But they were attacked because somebody thought they were Muslim, and they related Muslim to the attacks on the towers.

I lived in the Middle East for 4! years. I lived in Iraq for 4 months. I am married to an Arab, to a woman that is from Syria. I know the region probably as good as any American that has worked in that region in this country. Muslims are good people. They’re law-abiding people.

Muslims are not terrorists.

For some reason, after September 11th and the promotion of terrorism and understanding terrorism, a lot of people, being ignorant of the religion, of the region, they automatically thought this was about Muslims versus the United States. It’s not. It’s not.

There are phenomenal people in this world that are Muslim, that practice the Muslim religion. But there is a small group of people that use the Muslim religion is something that they promote that creates this war against us. It’s their mind, it’s their interpretation. Sometimes, I don’t even think it’s their interpretation. I think they know. They know, no doubt, the Muslim religion doesn’t call for the mass murdering of individuals and civilians.

It doesn’t.

But they would tell you, they would promote to you that it does. It doesn’t. And don’t ever think it does.

This isn’t about a fight against Muslims. This is a fight against terror. I think that’s one of the reasons I felt so good about going to Iraq to do what I had to do.

Attendee: Commissioner, coming from the Middle East, being a Muslim, thank you so much for saying that. After 9/11, there was a lot of misunderstanding.

Being an Arab and being a Muslim, like any terrorist group, these minorities have an agenda. They’re anarchists. They use religion as an excuse. They give it a certain spin.

For all of you guys here, consider yourself having an open invitation to visit me in Bahrain or anywhere else, and you can see for yourself what it’s all about. And thank you so much.

Coming from such a prominent person saying these kinds of things, I appreciate it very, very much. Thank you.

Attendee: Again, I would like to thank you for coming here. I think all of us greatly appreciate it. My question is when you said that after September 11th, whenever a jet would pass over, you would be shocked and you would ask all of those questions to yourself, do you still ask those questions whenever a jet or a plane passes over?

Bernard Kerik: Leave it to a kid. Yeah, she’s 35. Honestly? Yes, I still think about it. I live in New Jersey, and I don’t live far from Teterboro Airport, which is a private airport, and I live very close to Newark Airport.

There are many times that a low-flying jet over my house or over my office in New York City, when I see them, in my mind it just reverts and I think of sort of a torpedo. I look at that plane and I wonder why it’s so low. Why is it where it’s at? Why is there a plane, today, flying up the East River? It shouldn’t really be there. Do they have authorization to be there?

Yes, I still think about it.

It’s an odd thing. People like me, people that were there on that day, that experienced it, that lived it, there isn’t a day that goes by that you don’t think about some element of that day.

I wear a memorial band on my wrist that says, “In memory of WTC23 NYPD.” That stands for the 23 people I lost.

When you have that sort of loss and you witness that sort of devastation, you’re never going to not think about it. There is some point in a day, every single day, that I think about it, whether it’s a plane, whether it’s a name, whether it’s a song, whether it’s a smell. No matter what it is, I can just about guarantee for the rest of my life I will think about it, just as many, many others will that lived in New York City and that did not but had some relationship to the towers.

Attendee: Sir, just a quick question. Success doesn’t happen without failure, and I was wondering can you talk about a personal failure and how you got through it?

Bernard Kerik: Failures? Yeah, I can talk about failures.

Let me see. I guess the biggest would be the most recent. Most of you, the kids may not realize this, but most of you may know or may remember last year, just about a year ago, December 3rd of 2004, I was nominated by President Bush to become the Homeland Security Secretary.

It was, as I said that day in front of the President and the world, it was the honor of my lifetime. It was an honor on a number of different levels. One, I have a great admiration for this President and what he has done in combating terrorism, what he’s done for me personally in New York City, what he’s done for others in a number of different areas.

But I have an admiration for this man. So that was an honor, being nominated by him.

There was another honor that I had, that I was almost unaware of until I got into the Roosevelt Room. I got nominated in the Roosevelt Room, the room named after Teddy Roosevelt, the first Police Commissioner.

In that room, at the end of that room, on the opposite side of the conference table, is a big plague. And in that plague is the Congressional Medal of Honor that was given to Teddy Roosevelt.

So for me to nominated by the President, with the endorsement of Rudy Guilliani, my best friend, one of my closest friends, in that room, it was without a doubt one of the greatest honors in my life, if not the.

I won’t get into details. But for all of you parents out there, if you ever intend to go into government and you have a nanny, pay your taxes.

You can all read about this next year sometime. I’m in the process or doing my second book. But my wife and I, we paid taxes on our domestic servant, our nanny. There was a tax lap that we had to deal with, but we were dealing with it.

What I didn’t know until the Thursday after I was nominated, is that my nanny, her work papers were not real. They were false. Her social security number was not real, it was false. And because I was the man that was going to oversee Homeland Security and ultimately oversee the immigration department, going before the Congress, going before the Senate would have been nearly impossible. I didn’t want to put my wife, my family through it. And I decided to decline.

The President supported me either way, and ultimately basically said, “I understand your decision. I support it. I don’t agree with it. But I understand, and they will probably try to kill you if you do this.”

Therefore, I withdrew.

I will tell you it was an extremely difficult day for me. It was a difficult time in my life. I will also tell you that I made my wife probably the happiest woman since she had our kids. She was totally against me taking the job.

When I resigned and retired as Police Commissioner, she thought that was it. Then I wound up in Iraq. That didn’t go over well either, at all.

I came back from Iraq and I thought that was it. And then I get nominated for this job. She was not happy.

But I will say they say things happen for the best. I’ve had a great year. I got to see my son graduate from the Police Academy. He has since been promoted to detective in New Jersey. He’s in narcotics.

I got to see my daughter’s first day at school. I got to be here.

These are things that you sort of take for granted and you don’t realize you miss when you have a job like that.

When I was the Police Commissioner, I got up at 5:00, I was in the car at 5:30 in the morning, I was on the phone with Guilliani at 6:00, my day went until midnight or 1:00. I went to sleep at 1:00 to 1:30, and I was back up at 5:00 every day, 7 days a week, for the entire time I was in office, with the exception of September 11th and after, in which I barely slept at all.

So I know what public service does, and the parents will understand this.

When I was the Police Commissioner, I had a very young daughter, who was born 6 months before I was appointed. I was home one morning, I got to stay home for some reason. I got to stay home late, and my daughter was just about a year old, and I was in the bathroom shaving. And I looked over and I saw her holding onto the wall. And she went from the wall to the other wall. And I started screaming and I was losing my mind. It was the first time I saw her walk.

My wife came running into the bathroom and she said, “What is it?” I said, “Celine walked! She walked from that place to this place.” And my wife just casually looked at me and she turned around and walked away. And as she was walking, I heard her say, “She’s been walking for a week.”

That will give you an idea of the things you miss. So as bad as it was then, it’s okay today. What else? Anybody else?

Attendee: Sir, I have a question for you. All big events, good, bad, leave an imprint on us and hopefully make us do something greater in the future. And I wonder if such a huge event, such as September 11th, what has that done to you and has that inspired you, or how is that shaping your life today and tomorrow, too?

Bernard Kerik: A couple things. First of all, and I used to tell this to the cops that worked for me and the corrections officers that worked for me. It was sort of a personal rule I had, but I used to tell the people that worked for me, “Listen, no matter what happens,” and the parents will understand this in this room, “you have a fight with your wife, she cooked the wrong dinner, she laid out the wrong clothes, she didn’t lay out the clothes, you came home late, had too much to drink, whatever the case may be, whatever you’ve done, whatever the friction is about, when you get ready to walk out the door in the morning, give them a kiss, tell them ‘I love you,’ and go about your business. End it. End it.”

And sometimes, that’s extremely hard to do. But the bottom line is what I learned, more than anything else on September 11th, knowing the personal tragedies, hearing the personal stories and knowing many of the people involved on that day and the days after, there are many that wish they had and didn’t have a chance to.

It’s not only about September 11th, it’s about going to work, it’s about getting in a car accident, it’s about a personal tragedy that may happen, that you don’t think about.

Take every day one day at a time. Live life to your fullest. Take that dream that you have, fulfill it at all costs. And be happy. Do everything in your life to be happy, because there may come a point in time that you don’t have a choice otherwise.

And I think if there’s any lesson that I really learned, Steve and I and Jeff were talking last night, I’m an avid watch collector and I had a watch that I had for years, that I was holding in a safe for my son, so when he turned 21 I would give it to him.

September 11th happened. I didn’t see my son for about 2! weeks. I lived in my office. He was secluded in New Jersey. And I was very busy.

The first time I saw him after September 11th, when I knew I was going to see him, I took the watch out of the safe and I gave it to him. A small memento, but it’s the same thought process, same theory. You never know what’s going to happen tomorrow.

Live life today like it’s your last. One more?

Attendee: Sir, as a native New Yorker, I feel your pain. But I have a 4-year-old over there. How do we tell her what our pain is and we give them the real history?

Bernard Kerik: You know how you give it to them? There has to be an education, and this is something that I have. Go back to the rebuilding of the twin towers. I don’t know how many of you followed sort of the politics of the rebuilding of the towers. People came to me and said, “What do you think?” I said, “What do I think?” I said, “There are 2,700 people who died in those 2 buildings. I don’t want to get into details, but I can tell you that by no means was 2,700 people removed. It probably wasn’t 200, 300. They were pulverized. They disappeared.

Would you bury, would you build on a battlefield, on Gettysburg? No. So I don’t think, on the footprint of the tower, we should rebuild. Now they are not.

What they’re going to do instead is they’re going to have a museum. And they’re going to have an educational center. And they’re going to have things like that, so that we can teach people, we can teach our kids what happened, when it happened, why it happened, and what we have to do to make sure it never happens again.

So that’s what I think we should be doing. A couple more, 2 more?

Stephen Oliver: Any last questions?

Bernard Kerik: This is going to be the hardest one. I should have quit, I know.

Attendee: You said earlier, when you were young, you read magazines about the martial arts all you could. You said every time you saw Master Jeff Smith in them, did you ever cut them out of the magazines and hang them in your room or something?

Bernard Kerik: I’m going to be very delicate about this answer, because Master Smith is an old man and he’s got an extremely big head as it is. I want to go to lunch, and he won’t be able to get out that door.

But what I used to do is I used to collect every magazine. And there are binders. And I’m sure I don’t have to promote this for the magazine companies, but there are binders. And every magazine I would buy, I would put into these binders. And I had them for years. And ironically, just recently, in the last 3 or 4 years I guess, my wife and I moved and we packed up all of our stuff that was in 10 different storage places, and I have now put it into a facility.

When you’re in a position like mine, you get a lot of mementos, like Master Smith and Master Oliver, they get mementos and they get trophies and they get plaques and they get things. I have more than probably any one human being you could imagine. Thousands.

My wife does not allow them to be in the house. When we built our new house, she gave me a list of things that I was allowed to put in my office. It’s my office! I tried to explain that to her. The list stood. Letters, pictures of the President, fine. Pictures with me and Tony Blair, the Prime Minister of England, fine. I was knighted by the Queen of England, she let that stay. I was impressed.

Things like that, I was allowed to keep. Other things goes in storage.

Needless to say, I have one of the biggest bills you can imagine for one of those self-storage kind of places. And Jeff Smith is in there.