Azato’s School Days and Martial Arts

Part One

By Gichen Funakoshi

Translated & Edited by Patrick & Yuriko McCarthy

Editor’s Note: This article is the first of two excerpts from a new book, “Karatedo Tanpenshu,” a collection and new English translation of early writings of Funakoshi, historical photos and other materials compiled and translated by Patrick and Yuriko McCarthy. The orignal Funakoshi articles were written in 1934 for the Keio Gijuku Taiiku-kia Karate Bu Kaiho.

School Days

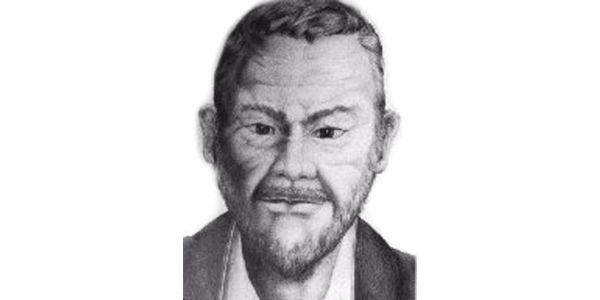

My teacher, Azato Ankoh, held an honorable rank not unlike that of a lower Daimyo in Japanese society. In spite of his first name being Ankoh, he use the pen name “Rinkakusai” when signing the plethora of literary compositions he authored. Since his youth Azato has been referred to as the “child prodigy” because he excelled in both the fighting traditions and in literary studies. By the time that the Ryukyu Kingdom was abolished, Azato had become a well-known politician holding the post of Minister of State.

A contemporary of Itosu Ankoh, Azato was more than just his esteemed colleague; they were also very close friends. Responsible for spear-heading the movement, which introduced the defensive tradition into the public school system. Itosu had such an enormous impact upon the growth and direction of karate that even local children knew his reputation. In fact, both Azato and Itosu were both regarded as brother Bushi and respected as such.

Together, Azato and Itosu had diligently studied the martial arts under the strict tutelage of Masumura Soken. An advocate of the Chinese ways, instruction under that taskmaster was always conducted early in the morning before dawn until the sun came up, without change or observation of holidays. During these times, Azato Sensei was also studying at the National school where he was peerless. Particularly, in the study of the Chinese classics, Azato was an honor student and received financial scholarship amounting to more than his tuition.

Being very close to his first son, Sensei liked me a lot and was, in many ways, like a second father. Moreover, he was always very frank with me. I remember once he told me how hard it was to teach his own son. Citing a Confucian proverb, describing the difficulties associated with a father training his own child, Sensei maintained that teaching other children allowed for more objectivity. “Now, I will teach you,” he told me, “in the future, please impart such learning to your friend, my son.” I was honored, and humbly complied.

The Martial Arts of Azato

During my teacher’s youth, few martial arts enthusiasts could ever afford the supplementary training equipment, which is commonly associated with the practice these days. However, Azato was an exception and it was because he was from a family of wealth and position that could afford such things. In fact, his home virtually looked like one big training facility. Both standing and hanging makiwara (impact training equipment) were located in various rooms of the Azato residence, along with other training equipment, which included wooden cudgels (club) and swords of various configurations, a wooden-man (a post with wooden arms and sometimes legs often associated with Chinese Kung Fu), stone weights, iron balls for grip-strength development, shield and machete, flails (nunchaku), iron truncheons (probably sais), and even a wooden horse for mounting practice and archery spotting. Master Azato had created a living environment where he could train at anytime and anywhere he liked.

Excelling in various martial arts, Sensei was particularly fond of horsemanship, which he studied under Megata Sensei, the trainer who groomed the Meiji Emperor himself. Sensei apparently decided to pursue Megata’s tutelage because his horsemanship was the trendy style being introduced from the West, which really appealed to a stalwart like Azato. Master Azato first observed Megata giving a lesson to a few students on the grounds next to the Hirakawa Emperor’s gate. Mr. Megata could tell that Sensei wanted to give the new saddle a try but was too modest to ask, so the trainer asked him instead. With some coaxing, Sensei finally accepted and was applauded by Megata for his brilliant performance and command over the reins. I think that Azato was a perfect example of the expression, “A person who excels in one thing can excel at everything.”

Sensei also loved archery and diligently studied under Master Sekiguchi, and like his teacher (Matsumura Sokon) before him, so did Azato study Jigenryu swordsmanship directly under the noted Japanese instructor Ishuin Yashichiro. However, among all the combative disciplines, it was the swordsmanship of Jigenryu that Sensei most favored. I remember that whenever Senseii got excited he used to say to me, “I’m ready to compete anytime if the opponent is serious.” In my opinion, Sensei was peerless in karate but judging by his preoccupation with Jigenryu, swordsmanship was his real passion.

At the risk of seeming presumptuous, I would, nevertheless, like to introduce a couple of anecdotes about Master Azato’s karate which I am personally familiar with. One night a burglar broke into Sensei’s residence, apparently not being aware of whose house it was. Had the burglar known that it was the home of Azato he would have never entered. Being awoken by noises in the house, Sensei knew that someone had broken into the house and jumped out of bed in an effort to apprehend the intruder. Coming face-to-face with the perpetrator in the living room it only took a moment to recognize that, in spite of dwarfing the man in size, Sensei was unable to capture the man. Moving with the agility of a gymnast, the man virtually bounced off the furniture, out the window, onto the wall surrounding the house and onto the roof of the house next door. Sensei gave chase but to no avail, as the man escaped without a trace. Later Sensei came to learn that a man well known for testing the skills of those considered masterful staged the incident. Such things often happened during Okinawa’s old Ryukyu kingdom.

One day Sensei and his good friend, Itosu Ankoh, were confronted by a small throng of 20 or 30 young men. Seriously mismatched, and in a less than accommodating location, the two decided to bolt taking refuge in a nearby house. At least there they could wait until the throng decided to disperse and leave, or fight them on more equal terms. Wound up an set upon fighting, the young men swarmed over the house like bees to a hive. During their assault on the house Azato leaped out from the window and surprised the hoodlums when he began to dispatch them. Engaging the gang on the other side of the house, Master Itosu was able to quickly discourage anyone else from continuing to act foolishly.

In spite of using only a single blow to dispatch each of the hoodlums that he confronted, Azato’s defense was brutally effective, leaving some of the young offenders seriously injured. In contrast to Azato’s confrontation, Itosu left more victims lying around the back of the house, but seriously injured no one. Judging by this anecdote one might be able to better understand the varying ways in which two experts might handle the same dangerous situation.

Mister Azato was well known for his incredible strength. When he was just 17 years old he walked to his home from Kyozuka, a distance of 4 km, carrying two large stones weighing more than 30 kg each on his shoulders. Such tests of strength often took place on the moonlit footpaths of old Okinawa when young men sought to establish reputations for themselves performing various feats of strength and bravery. Sensei was one such man and his awesome reputation for strength and technique earned him so much respect that he was referred to as Bushi Azato.