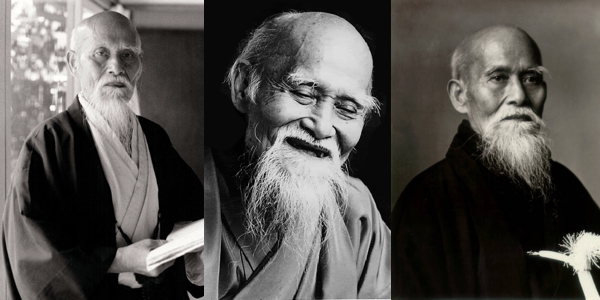

Although aikido is a relatively recent innovation within the world of martial arts, it is heir to a rich cultural and philosophical background. Aikido was created in Japan by Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969). Before creating aikido, Ueshiba trained extensively in several varieties of jujitsu, and in swordsmanship. Ueshiba also immersed himself in religious studies and developed an ideology devoted to universal socio-political harmony. Incorporating these principles into his martial art, Ueshiba developed many aspects of aikido in concert with his philosophical and religious ideology.

Aikido, as Ueshiba conceived it in his mature years, is not primarily a system of combat, but rather a means of self-cultivation and improvement. Aikido has no tournaments, competitions, contests, or “sparring.” Instead, all aikido techniques are learned cooperatively at a pace commensurate with the abilities of each trainee. According to the founder, the goal of aikido is not the defeat of others, but the defeat of the negative characteristics which inhabit one’s own mind and inhibit its functioning.

At the same time, the potential of aikido as a means of self-defense should not be ignored. One reason for the prohibition of competition in aikido is that many aikido techniques would have to be excluded because of their potential to cause serious injury. By training cooperatively, even potentially lethal techniques can be practiced without substantial risk.

It must be emphasized that there are no shortcuts to proficiency in aikido (or in anything else, for that matter). Consequently, attaining proficiency in aikido is simply a matter of sustained and dedicated training. No one becomes an expert in just a few months or years.

Aikido History

Aikido’s founder, Morihei Ueshiba, was born in Japan on December 14, 1883. As a boy, he often saw local thugs beat up his father for political reasons. He set out to make himself strong so that he could take revenge. He devoted himself to hard physical conditioning and eventually to the practice of martial arts, receiving certificates of mastery in several styles of jujitsu, fencing, and spear fighting. In spite of his impressive physical and martial capabilities, however, he felt very dissatisfied. He began delving into religions in hopes of finding a deeper significance to life, all the while continuing to pursue his studies of budo, or the martial arts. By combining his martial training with his religious and political ideologies, he created the modern martial art of aikido. Ueshiba decided on the name “aikido” in 1942 (before that he called his martial art “aikibudo” and “aikinomichi”).

On the technical side, aikido is rooted in several styles of jujitsu (from which modern judo is also derived), in particular daitoryu-(aiki) jujitsu, as well as sword and spear fighting arts. Oversimplifying somewhat, we may say that aikido takes the joint locks and throws from jujitsu and combines them with the body movements of sword and spear fighting. However, we must also realize that many aikido techniques are the result of Master Ueshiba’s own innovation.

On the religious side, Ueshiba was a devotee of one of Japan’s so-called “new religions,” Omotokyo. Omotokyo was (and is) part neo-shintoism, and part socio-political idealism. One goal of omotokyo has been the unification of all humanity in a single “heavenly kingdom on earth” where all religions would be united under the banner of omotokyo. It is impossible sufficiently to understand many of O-sensei’s writings and sayings without keeping the influence of Omotokyo firmly in mind.

Despite what many people think or claim, there is no unified philosophy of aikido. What there is, instead, is a disorganized and only partially coherent collection of religious, ethical, and metaphysical beliefs which are only more or less shared by aikidoists, and which are either transmitted by word of mouth or found in scattered publications about aikido.

Some examples: “Aikido is not a way to fight with or defeat enemies; it is a way to reconcile the world and make all human beings one family.” “The essence of aikido is the cultivation of ki (a vital force, internal power, mental/spiritual energy).” “The secret of aikido is to become one with the universe.” “Aikido is primarily a way to achieve physical and psychological self- mastery.” “The body is the concrete unification of the physical and spiritual created by the universe.” And so forth.

At the core of almost all philosophical interpretations of aikido, however, we may identify at least two fundamental threads:

(1) A commitment to peaceful resolution of conflict whenever possible.

(2) A commitment to self-improvement through aikido training.

The Dojo

A dojo can be defined as:

A place where the Way of Aikido is practiced.

A place for forging the body and spirit.

A place for enlightenment.

A dojo is not a gym for mere “working out”.

It is more than just a building.

It is a sacred place that cannot be defined by it’s geographical location, the height of it’s walls, or the value of it’s contents.

It is defined by the spirit emanating from within it-individual, collective, and it’s universal spirit.

A dojo should be appreciated by seeing it with one’s heart.

It is the commitment and responsibility of all students, and part of our training to make the dojo a better place, physically and spiritually. The physical state of the dojo is a reflection of it’s students. We clean what needs to be cleaned, we fix what needs to be fixed and participate in dojo activities. We shouldn’t need to asked or told, we should observe and respond accordingly.

In return for the instruction that we receive it is our responsibility to maintain and improve the dojo. Thus, the dojo should improve, grow and evolve as the student body evolves.

The instruction that we receive from our sensei (and all teachers) is a gift that is given to us. The value of that gift is not covered by our dues, and the value is different for every student.

You must be prepared to give as well as receive, as we are all teachers and we are all students. It is part of your responsibility to help beginners and nurture interest and comradiery in the dojo.

Training

Aikido practice begins the moment you enter the dojo! Trainees ought to endeavor to observe proper etiquette at all times. It is proper to bow when entering and leaving the dojo, and when coming onto and leaving the mat. Approximately 3-5 minutes before the official start of class, trainees should line up and sit quietly in seiza (kneeling) or with legs crossed.

The only way to advance in aikido is through regular and continued training. Attendance is not mandatory, but keep in mind that in order to improve in aikido, one probably needs to practice at least twice a week. In addition, insofar as aikido provides a way of cultivating self-discipline, such self-discipline begins with regular attendance.

Your training is your own responsibility. No one is going to take you by the hand and lead you to proficiency in aikido. In particular, it is not the responsibility of the instructor or senior students to see to it that you learn anything. Part of aikido training is learning to observe effectively. Before asking for help, therefore, you should first try to figure the technique out for yourself by watching others.

Aikido training encompasses more than techniques. Training in aikido includes observation and modification of both physical and psychological patterns of thought and behavior. In particular, you must pay attention to the way you react to various sorts of circumstances. Thus part of aikido training is the cultivation of (self-)awareness.

The following point is very important: Aikido training is a cooperative, not competitive, enterprise. Techniques are learned through training with a partner, not an opponent. You must always be careful to practice in such a way that you temper the speed and power of your technique in accordance with the abilities of your partner. Your partner is lending his/her body to you for you to practice on – it is not unreasonable to expect you to take good care of what has been lent you.

Aikido training may sometimes be very frustrating. Learning to cope with this frustration is also a part of aikido training. Practitioners need to observe themselves in order to determine the root of their frustration and dissatisfaction with their progress. Sometimes the cause is a tendency to compare oneself too closely with other trainees. Notice, however, that this is itself a form of competition. It is a fine thing to admire the talents of others and to strive to emulate them, but care should be taken not to allow comparisons with others to foster resentment, or excessive self-criticism.

If at any time during aikido training you become too tired to continue or if an injury prevents you from performing some aikido movement or technique, it is permissible to bow out of practice temporarily until you feel able to continue. If you must leave the mat, ask the instructor for permission.

Although aikido is best learned with a partner, there are a number of ways to pursue solo training in aikido. First, one can practice solo forms (kata) with a jo or bokken. Second, one can “shadow” techniques by simply performing the movements of aikido techniques with an imaginary partner. Even purely mental rehearsal of aikido techniques can serve as an effective form of solo training.

It is advisable to practice a minimum of two hours per week in order to progress in aikido.

Etiquette

Proper observance of etiquette is as much a part of your training as is learning techniques. In many cases observing proper etiquette requires one to set aside one’s pride or comfort. Nor should matters of etiquette be considered of importance only in the dojo. Standards of etiquette may vary somewhat from one dojo or organization to another, but the following guidelines are nearly universal. Please take matters of etiquette seriously.

1. When entering or leaving the dojo, it is proper to bow in the direction of O-sensei’s picture, the kamiza, or the front of the dojo. You should also bow when entering or leaving the mat.

2. No shoes on the mat.

3. Be on time for class. Students should be lined up and seated in seiza approximately 3-5 minutes before the official start of class. If you do happen to arrive late, sit quietly in seiza on the edge of the mat until the instructor grants permission to join practice.

4. If you should have to leave the mat or dojo for any reason during class, approach the instructor and ask permission.

5. Avoid sitting on the mat with your back to the picture of O-sensei. Also, do not lean against the walls or sit with your legs stretched out. (Either sit in seiza or cross-legged.)

6. Remove watches, rings and other jewelry before practice as they may catch your partner’s hair, skin, or clothing and cause injury to oneself or one’s partner.

7. Do not bring food, gum, or beverages onto the mat. It is also considered disrespectful in traditional dojo to bring open food or beverages into the dojo.

8. Please keep your fingernails (and especially toenails) clean and cut short.

9. Please keep talking during class to a minimum. What conversation there is should be restricted to one topic – Aikido. It is particularly impolite to talk while the instructor is addressing the class.

10. If you are having trouble with a technique, do not shout across the room to the instructor for help. First, try to figure the technique out by watching others. Effective observation is a skill you should strive to develop as well as any other in your training. If you still have trouble, approach the instructor at a convenient moment and ask for help.

11. Carry out the directives of the instructor promptly. Do not keep the rest of the class waiting for you!

12. Do not engage in rough-housing or needless contests of strength during class.

13. Keep your training uniform clean, in good shape, and free of offensive odors.

14. Please pay your membership dues promptly. If, for any reason, you are unable to pay your dues on time, talk with the person in charge of dues collection. Sometimes special rates are available for those experiencing financial hardship.

15. Change your clothes only in designated areas (not on the mat!).

16. Remember that you are in class to learn, and not to gratify your ego. An attitude of receptivity and humility (though not obsequiousness) is therefore advised.

17. It is usually considered polite to bow upon receiving assistance or correction from the instructor.

18. During class, if the instructor is assisting a group in your vicinity, it is frequently considered appropriate to suspend your own training so that the instructor has adequate room to demonstrate.

“Eight forces sustain creation:

movement and stillness, solidification and fluidity,

extension and contraction, unification and division. “

” Techniques employ four qualities that reflect the nature of our world. Depending on the circumstance, you should be: hard as a diamond, flexible as a willow,

smooth-flowing like water, and as empty as space. ”

excerpted from

The Art of Peace, Teachings of the Founder of Aikido

Taken from the Aikido Primer

by Eric Sotnak

sotnak @ bigfoot.com