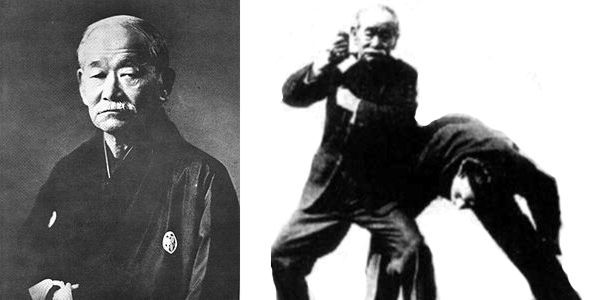

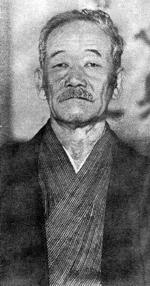

Indeed, Jigoro Kano was many things to many people. Like Sir Thomas More, he was a man for all seasons. His many worlds encompassed much of value to Japan. From scattered quotes taken from various sources close to him, we can only glimpse Jigoro Kano, the man:

Indeed, Jigoro Kano was many things to many people. Like Sir Thomas More, he was a man for all seasons. His many worlds encompassed much of value to Japan. From scattered quotes taken from various sources close to him, we can only glimpse Jigoro Kano, the man:

“He used to take an umbrella with him every day because he didn’t like to worry about whether or not it would rain.”

“When he returned home, he would go straight into the living room, which meant on most days I would not see my father at all.”

“Just after I graduated from Waseda University, he sent me a cable: ‘Your father has been looking for a wife for you. What sort of woman do you have in mind for a wife?’ Less than three years later, I married his daughter.”

“He was very strict with us at school. I had to get up at 5 o’clock every morning and help clean the rooms and the garden.”

“He was so proud of his legs he used to pull up his hakama just to show off his big calves.”

“He wept when he heard of my sister’s (his daughter’s) death.”

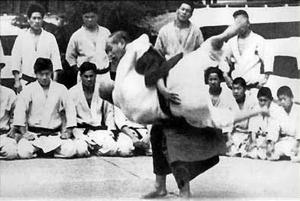

He was a perfectionist, a disciplinarian and a traditionalist. But, at the same time, an innovator, an internationalist and a man of great generosity. More important, he was a famous educator and the father of modern sports in Japan.

But above all, Jigoro Kano was the founder of judo!

When he first saw the light of day on Oct. 28, 1860, Japan’s feudal period was rapidly drawing to a close. Across the seas in America, the United States was embarked on a tragic civil war. Just as today, it was a time of turmoil and change around the world.

He was fortunate enough to be born into a family that was reasonably well off, at least well enough placed to get Jigoro into the elite Tokyo Imperial University. His grandfather had launched the family into the business of making sake in Nada, Shiga Prefecture, near the Biwa Lake in central Japan. In fact, it was this same sake-brewing clan that organized the other sake makers in the area to help finance the Fujimi-cho Dojo which served as the Kodokan in the latter half of the 1880s.

Since Jigoro’s father was not the eldest son, the sake business was not passed down into his hands. Even at that, his father did all right for himself at Kobe-Jigoro’s birthplace-as both a Shinto priest -and a high-ranking government official in charge of purchasing agents for shipping lines. It was this side of the Kano family that prompted the building of Japan’s first steel ships coastal vessels designed to carry sake.

The third son in a family of three boys and two girls, young Jigoro was physically weak in his early years. In fact, he was beaten up so often by local bullies he resolved to strengthen himself the best way he could. It was this unrelenting drive to learn how to defend himself that eventually led to his formulation of judo. One wonders what would have happened had Jigoro Kano been a big brute of a man instead of the 5-foot, 2-inch, 90-pound weakling he was in his teens.

The third son in a family of three boys and two girls, young Jigoro was physically weak in his early years. In fact, he was beaten up so often by local bullies he resolved to strengthen himself the best way he could. It was this unrelenting drive to learn how to defend himself that eventually led to his formulation of judo. One wonders what would have happened had Jigoro Kano been a big brute of a man instead of the 5-foot, 2-inch, 90-pound weakling he was in his teens.

Jujitsu was flourishing during Jigoro’s boyhood. One might even term the mid-19th century the golden age of jujitsu. So it was with rather anxious expectation Jigoro looked forward to moving to Tokyo, where most of the jujitsu activity was going on. When he was 17, his father ordered him to go to the capital on board one of the sake-carrying steel ships, but he insisted on traveling by land. His father relented-and a good thing, too, because the vessel he was to sail on broke up in stormy seas en route to Tokyo and sank.

Obsessed With Learning

Jigoro enrolled the following year at Tokyo Imperial University at the age of 18. When he wasn’t in class or studying, he would go off in search of an osteopath because they had all received jujitsu training. Apparently, he was still obsessed with the desire to learn the art of manly self-defense and concluded jujitsu offered him the best hope. His search finally led him to the door of a bone doctor in Nihonbashi named Teinosuke Yagi who promised to introduce him to a jujitsu teacher living in the neighborhood.

Jigoro Kano had actually started his training in jujitsu at the age of 17, but his instructor, Ryuji Katagiri, felt he was too young for serious training. As a result, Katagiri gave him only a few formal exercises for study and let it go at that. The determined young man was not about to be put off so easily, however, and finally wound up at the dojo of Hachinosuke Fukuda, a master in the Tenjin-Shinyo School of Jujitsu who had been recommended by Dr. Yagi.

Fukuda stressed technique over formal exercises, or kata. His method was to give an explanation of the exercises, but to concentrate on free-style fighting in practice sessions. Jigoro Kano’s emphasis on “randori” in judo undoubtedly found its beginnings here under Fukuda’s influence. The Kodokan’s procedure of teaching beginners the basis of judo, then having them engage in randori’ and only after they had attained a certain level of proficiency, teaching them the formal kata, came from Fukuda and a later sensei named Iikubo.

In 1879, a year after Jigoro started working out at Fukuda’s dojo, the jujitsu master suddenly became gravely ill and died at the age of only 52. The 19-year-old youth soon joined another branch of the Tenjin-shinyo-ryu run by a 62-year-old jujitsu instructor named Masatomo Iso. Located in the Kanda section of Tokyo near the center of the city, Iso’s dojo was known for its excellence in kata. Iso, himself, was only 5 feet tall, but had a powerful body and an energetic personality.

In 1879, a year after Jigoro started working out at Fukuda’s dojo, the jujitsu master suddenly became gravely ill and died at the age of only 52. The 19-year-old youth soon joined another branch of the Tenjin-shinyo-ryu run by a 62-year-old jujitsu instructor named Masatomo Iso. Located in the Kanda section of Tokyo near the center of the city, Iso’s dojo was known for its excellence in kata. Iso, himself, was only 5 feet tall, but had a powerful body and an energetic personality.

Over the next two years, Jigoro Kano ate, drank and slept jujitsu, practicing night and day at the point of exhaustion. Things got so bad he was even having nightmares about the martial art, shouting jujitsu terms in his sleep and kicking out at his quilt.

The sensei saw his dedication and promise and soon made him an assistant. Jigoro instructed 20 or 30 students, starting with kata and then moving on to free fighting.

By the time he was 21 years old in 1881, Kano had become a master in Tenjin-shinyo-ryu jujitsu. But Iso, like Fukuda before him, became ill and Kano decided to move on, feeling he still had much to learn and wanting to study rather than teach.

The next step seemed almost inevitable. Jigoro Kano met Tsunetoshi Iikubo, master of the Kito School of Jujitsu, and began training at his dojo. Even when no one else showed up, Kano would work out alone. Like Fukuda, Iikubo put the stress on free fighting and he was especially skillful at teaching nage-waza.

Reforming Jujitsu

It was during these early jujitsu training days Jigoro Kano worked out some new throws and turned his attention more and more to ways of reforming jujitsu into some kind of new system. While practicing at the Tenjin-shinyo Training Hall, he ran up against a big, 200-pound bruiser named Kenkichi Fukushima. Outweighed by 100 pounds, the lightweight youth invariably lost to the bigger man. He wanted to beat Fukushima so badly he could taste it, studying everything he could get his hands on books on sumo techniques, training books from abroad, etc.

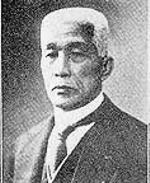

Finally, Jigoro worked out a new technique. The next time he met his burly rival he charged in low, lifted Fukushima onto his shoulders, whirled him around and easily tossed him on the mat. He promptly dubbed his new throw “kata-garuma,” or shoulder whirl. Other throws he worked out include “uki-goshi” (rising hip throw) and “tsuri-komi-goshi” (lift-pull hip throw).

The original idea was merely to reform jujitsu rather than found a new system. Kano was well aware of the shortcomings, but felt these could be weeded out with the result that jujitsu could be beneficial to young men-not only as a martial art, but also as a form of physical education as well as training and discipline of the spirit; in short, a valuable preparation for one’s daily life.

He dedicated himself to formulating a system of reformed jujitsu founded on scientific principles, integrating combat training with mental and physical education. He borrowed the “katamewaza” (mat techniques) and “atemi-waza” (throwing techniques) of Kito-ryu, holding onto those techniques that conformed to scientific principles and rejecting all others. All harmful and dangerous techniques were eliminated.

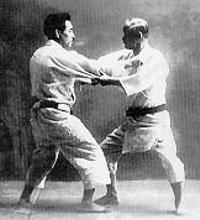

When 22-year-old Jigoro Kano took nine of his private students from the Kito-ryu Training Hall in February 1882 and set up his own dojo in Eisho-ji Temple, judo didn’t automatically spring into being. In fact, Kito-ryu master Iikubo came to the temple two or three times a week to help instruct Kano’s students. So what they were getting was more jujitsu than judo training. Two years were to elapse before the by-laws of the first Kodokan were drawn up.

Much has been written about those early days at Eisho-ji, and it is this temple that is generally regarded by most people as the birthplace of judo. The transition from jujitsu to judo was made slowly but surely, although it is difficult to pinpoint the day when what that handful of students were learning was no longer jujitsu, but judo.

It might have been the day when Kano first defeated Iikubo. Until then he had never managed to get the better of the Kito-ryu stylist. But that day in randori practice, Kano blocked every move Iikubo made, then called on his “uke-waza” and “sumi-otoshi” to throw the jujitsu master no less than three times.

Kano explained: “Force your opponent to make his body rigid and lose his balance, and then when he is helpless, you attack.”

Iikubo replied: “From now on, you teach me.”

Iikubo soon retired as an instructor and Kano finally received his accreditation as a Kito-ryu master. Apparently, Iikubo was a vigorous fighter because every time he came to teach at the 12-mat dojo at Eisho-ji, training got a bit more violent than usual. And the tablets would come tumbling down!

A Chiding Buddhist Priest

It seems the converted dojo adjoined the main hall of the temple in which the image of Buddha was located together with hundreds of mortuary tablets presented by various worshipers. And every time Jigoro Kano and his students practiced, these clay tablets bounced up and down and banged against each other, several falling to the floor. This went on until one day head priest Choshumpo rushed into the dojo and declared: “He may be young, but Mr. Kano is really an outstanding man. What a fine person he would be if he would only leave this judo alone.”

Despite the priest’s occasional protestations, the practice sessions continued at Eisho Temple. Sometimes the training would be so rough the dojo floor sagged and even broke in some places. Nighttime would find the indefatigable Kano crawling under the floor with a lantern repairing the broken boards.

The year before, in 1881, Kano had graduated from Tokyo Imperial University and soon secured a position as a literature instructor at Gakushuin (Peer’s School), an exclusive school for the children of high-born Japanese. His instruction at the dojo had to be sandwiched between his work at the school and the preparation for the next day’s classes. It wasn’t unusual for him to keep going into the wee hours of the morning.

He was tough on both his academic and his judo students, a disciplinarian of sorts. But he was also a very generous man, offering his judo students barley tea and rice mixed with lotus roots at the temple. He provided his poorer students with practice clothes-jujitsu-gi, which he even laundered for them.

Priest Choshumpo finally came to the end of his tether and presented Kano with an ultimatum: “Either leave the temple or give up practice there.” Being an enterprising young man, Kano made a deal for using an empty lot next to Eisho-ji and built a tiny training hall there measuring only 12 by 18 feet. But this was only a temporary move and Kano set up his next dojo in his own home in 1883. With 20 mats, it was the largest training hall up to this time.

But 1884 was the key year when the Kodokan by-laws were drawn up. Kano declared, “Taking together all the merits I have acquired from the various schools of jujitsu, and adding my own devices and inventions, I have founded a new system for physical culture, mental training and winning contests. This I call Kodokan judo. ”

Randori and kata became firmly established and even made the subjects of lectures and debates as well as a part of education. But the big difference from jujitsu was the “do” in judo-finding the way. Kano saw judo, then, as a way of life. He saw it in terms of a sport, whereas jujitsu was merely another of the martial arts, a method of defense. The dangerous techniques of jujitsu were eliminated from the judo contests, but retained as part of judo’s defense system. This especially applied to “atemi.”

Another essential difference from jujitsu was judo’s application of “kazushi,” a theory devised by Jigoro Kano during his jujitsu training and used so successfully against Kito-ryu master Tsunetoshi Iikubo. “Using a minimum amount of strength, it is possible to throw your opponent if you force him off-balance by breaking his posture.” According to Kazuzo Kudo, kyu-dan director of the Kodokan and author of “Dynamic Judo,” Jigoro Kano’s “fame and greatness are based on this principle just as much as they are on him as the founder of judo.”

Fierce Rivalry Springs Up

As might be expected, a fierce rivalry sprang up between judo and jujitsu. The martial art had been steadily declining toward the end of the 19th Century and its masters were getting desperate to hold onto their students who were beginning to trickle away to judo. Kudo says reports of street fighting by judo and jujitsu students jealous of their own prowess were exaggerated. Critics claim jujitsu had a bad reputation for terror tactics by goon squads and it made rowdies out of youths.

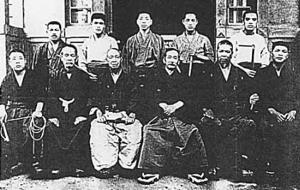

Among the now-famous pupils of Kano in those early days were Yoshitsugi Yamashita, who later taught judo to President Theodore Roosevelt; Tsunejiro Tomita, father of the noted author of the judo novel “Sugata Sanshiro”; Seiko Higuchi; Shiro Saigo, who became a student in 1884 at the age of 16 and developed into a kind of judo genius, especially noted for his “yama-arashi” and “harai-goshi”; and Sakujiro Yokoyama who was such a fighting demon he was known as “Devil Yokoyama.”

These students were Kano’s judo stalwarts in the early contests with the police and other jujitsu dojo. The first “shiai” probably started informally in the Kodokan, but by 1884 the first Red and White Contest was inaugurated, continuing biannually until the present day. The following year the Kodokan won its first shiai-against the police, who had adopted jujitsu. “Kagami-Biraki,” or Rice-Cake Cutting Ceremony, was instituted in 1884 and has been observed ever since on the second Sunday in January.

By 1886, Kano changed the Kodokan once again from his home in Koji-machi to the Fujimi-cho residence of the Meiji Era magnate, Baron Yajiro Shinagawa. And it was here during the next three or four years that Kodokan judo achieved supremacy over the rival jujitsu schools.

Although he was a man of many interests, Jigoro Kano always thought in terms of judo. To him, a kyudoka was a judoman using a bow and arrow and a kendoka was a judoka with a sword.

Once the Kodokan was firmly established, Kano’s thoughts turned toward the spread of judo on a nationwide basis and eventually throughout the world. In fact, Kano went on his first overseas visit in 1889 to spread the good word about this new Japanese sport.

In the latter 1880s Yajiro Shinagawa, a magnate of the Meiji Period, was appointed ambassador to England and asked Kano to take care of his house at Koji-machi while he was gone. The young judo master agreed, but was soon tempted into turning the house into a judo dojo. Thus, Ambassador Shinagawa’s home became the next Kodokan, with 40 mats available for practice. Fortunately, Shinagawa was a generous and broadminded man.

By 1892, there were still less than 100 judo students practicing at the Kodokan. Kano preferred tachi-waza (standing techniques), to ne-waza (mat work), at which he was less skillful and, thus, avoided whenever possible. Indeed, he had a tough time of it when he was forced onto the mat. To compensate for this, his assistants and students trained especially hard in ne-waza in order to beat jujitsu rivals.

Ninety-one-year-old Saburo Nango, a nephew of Jigoro Kano and 18 years his junior, remembers doing randori with his uncle in those early years. “He was small, but a very good technician,” Nango recalls. “He was also fast and very strong.”

Nango also occasionally thinks back to the first judo kangeiko when students ran from the dojo at Kami-ni-bancho to Toranomon and back again in the dead of winter-a distance of six or seven miles. The first kangeiko was launched in 1894, while the first shochugeiko (midsummer training) began two years later in 1896.

Management of the Kodokan was handled by Kano himself until 1894 when a consultative body, the Kodokan Council, was set up. To say that Kano was busy would be putting it mildly. He usually rode to work in a ricksha as headmaster of Gakushuin, or Peer’s School, but only after spending two hours instructing at hi s own Kobun Gakuen (a school organized by Kano for Chinese students). After work, he would go to the Kodokan and supervise the training. Then late at night, he would prepare his lectures for the following day.

Kano became headmaster of Gakushuin at the age of only 25. It customarily admitted only the children of the Imperial family and titled, upper-class families, but after Kano took over, enrollment was enlarged to include pupils from other social strata, including commoners. According to Kazuzo Kudo, Kano ranks along with Shain Yoshida as one of Japan’s modern educators. As headmaster of both Gakushuin and the Tokyo Teachers Training School (the present-day Tokyo University of Education) off and on for more than a quarter of a century, Jigoro Kano laid the basis of modern education in Japan.

He turned Gakushuin into a boarding school, allowing his students to go home only on weekends. He refused to go along with the commonly accepted notion that the highborn were inherently superior in mental potential and opened the doors to commoners-a revolutionary move at the time. He also had his students perform menial tasks in order to discipline them and teach them humility. Thus, the entire environment changed under Kano’s administration, and not too surprisingly the parents of the students were full of admiration for the wonders being worked at Gakushuin.

Unusually Strict with Students

Nango remembers Kano as unusually strict. “When I was a student under him,” Nango explained, “I had to get up at 5 o’clock every morning and help clean the rooms and the garden.”

Dr. T. Morohashi, today one of the leading professors of Chinese culture at Tokyo University, called Kano sensei a “confident and broad-minded president.” When he entered Tokyo Teachers Training School in 1904, Kano was 44 years old. He called in a few of the students and asked them to speak their minds frankly. Noting the meager resources of the library, Morohashi insisted improvement of the library should take precedence over building a big dojo. Kano replied one could read anywhere, but one certainly couldn’t practice judo any old place. Even at that, the next time he met with the vice minister of education, Kano pushed hard for a boost in the school library budget.

Jigoro’s feelings about education are summed up in a statement he made at the Kodokan’s 50th anniversary in 1934. “Nothing under the sun is greater than education. By educating one person and sending him into the society of his generation, we make a contribution extending a hundred generations to come.”

Kano often was at odds with superior authorities in the field of education, but never once submitted a letter of resignation over the matter. That’s because he never thought he was wrong! Dr. Morohashi also accused Kano of delivering boring lectures, recalling once when only three students showed up for one of his lectures. Kano was so angry he cried: “Everyone in this course is dropped! ”

It was in August of 1891 Jigoro Kano married Sumako, the eldest daughter of Seisei Takezoe-onetime ambassador to Korea. They had nine children-six daughters and three sons, including Risei, present head of the Kodokan and the All-Japan Judo Federation. Atsuko, Kano’s youngest daughter, is the only other surviving child and is married to Masami Takasaki–an 8-dan judoka and Kodokan director.

A typical “kokushi” father, Kano ruled his family with an iron hand; his word was law and disobedience unthinkable. The eldest daughter, Noriko, wrote of her reminiscences of her famous father. Tall and pretty with a well-shaped nose, she was the favorite of her parents and perhaps closer than the others to her father. Even at that, she writes: “When he returned home, he would go straight into the living room, which meant on most days I would not see my father at all.”

Risei Kano remembers his father as broad-minded and a man with an international outlook. He learned judo techniques from his father at the home dojo, but simply wasn’t the athletic type. Although Jigoro Kano was a strict disciplinarian, he also had an emotional, warm-hearted side. “He wept,” Risei recalls, “when he heard of Noriko’s death.”

Although Kano provided his children with fine training and a good education, he was so busy most of the time his family must have been lonely without him. “He left the children almost entirely to the mother,” Noriko writes in her Recollections of My Father. Sometimes, all they would see of their father was when they lined up at the entrance of their home to welcome him back-” O-kaeri-nasai mase”-before he disappeared for the day into the living room.

Commands Instant Obedience

Those were the days of Meiji (1868-1912) when the father was a benevolent despot, when children were seldom seen and rarely heard, when they were not allowed to venture into the living room if he were there, when they were not allowed to take their meals with him, when they feared and respected rather than loved him and when his commands elicited instant obedience from them.

Both Kudo and Nango remember visiting Kano at his home, usually in the morning. Kano was not always burdened with weighty matters, for Kudo recalls they often talked of trifling things. “Kano sensei never smoked, but he liked his sake and his face got red quickly when he was drinking.” He refused to indulge in the Japanese tradition of exchanging sake cups with fellow drinkers and drinking from theirs. Since this custom was greatly admired in the rural areas, farmers invariably wanted to swap sake cups with Kano, but he considered it to be an unhealthy practice and grew angry when they asked him.

Jigoro Kano only stood five feet, two inches but he weighed over 165 pounds. He had broad shoulders and chest and big calves. Kudo says “Shihan was so proud of his calves he was always pulling up his hakama to show them off.” Kudo was also amazed at Kano’s speed. “I was surprised at how quickly he threw me.”

According to Kudo, Jigoro Kano was always smiling, even when he was angry. “He laughed deeply when he was pleased.” Takasaki, his son-in-law, confirmed this by saying Kano had a keen sense of humor, and although easily angered, he was also quick to laugh.

Takasaki also remembers Kano liked sake, but knew his limit and usually stopped before he had too much. “If he over-imbibed, he invariably got sick.”

In his active days no one practiced harder than Jigoro Kano. He kept at it until he was a mass of wounds, barely able to stagger home. His judogi is on display at the Kodokan and is made of brown linen on the outside and cotton inside. He repaired it himself with kite twine. With the bottom in tatters, the judogi is discolored with oil and sweat-mute testimony to Jigoro Kano’s strength and fierce fighting spirit.

In his active days no one practiced harder than Jigoro Kano. He kept at it until he was a mass of wounds, barely able to stagger home. His judogi is on display at the Kodokan and is made of brown linen on the outside and cotton inside. He repaired it himself with kite twine. With the bottom in tatters, the judogi is discolored with oil and sweat-mute testimony to Jigoro Kano’s strength and fierce fighting spirit.

In 1907 Kano had the sleeves and pants of the judogi fully lengthened to cover the arms and legs and protect the elbows and knees. The jacket was also shortened. Thus, the judogi assumed the final form in which it is still used today. This was in sharp contrast to the early days when judoka wore shorts and a jacket that left half the arms as well as the knees and legs exposed. By the time Kano was 60 he gave up wearing a judogi, simply putting on a haori (formal shirt) and performing his kata in that way.

The Kodokan officially became a foundation in May 1909, and two years later in April 1911 the Judo Teachers’ Training Department was set up. Then in 1922, the Kodokan Dan Grade Holders Association was organized, followed by the Judo Medical Research Society in 1932.

When Kano called judo “a way of human development understandable by people all over the world,” he was attempting to formulate an idea he had of organizing an international judo federation to spread interest in judo. By 1912, the Shihan had made no less than nine trips abroad to create interest in the new Japanese sport.

By this time, many foreigners-mostly sailors and merchant seamen-were training at the Kodokan. Books on judo in foreign languages were being written. Thus, before the outbreak of World War 1, dojo had been set up in the United States, Britain, France, Canada and India as well as in Russia, China and Korea.

A Russian by the name of A. Oshichenikov visited Japan in 1911 and spent six years training at the Kodokan. Before he returned home in 1917, he had been promoted to nidan. He not only proceeded to teach judo techniques to the Red Army and the secret police, but was also instrumental in organizing Russia’s judo-like sport of sambo in the 1930s.

Yoshitsuge Yamashita’s staging of a worldwide jujitsu meet at the Japan Police Ministry in 1893 must have started Kano thinking along the same lines for judo. But first he had to spread it throughout Japan. Nango recalls Kano lecturing him along the following lines: “Japan is a small, mountainous and highly-populated country, short of resources, and so we Japanese must perform to the utmost of our ability. We must mutually support one another and make the best use of energy to keep Japan independent.” Here are embodied two of his key judo principles, “the best use of energy” and “mutual prosperity.”

Besides his association with Gakushuin and the Tokyo Teachers Training School (later known as Tokyo Education College), Kano was responsible for founding Kobun Gakuen, a special school for Chinese students which was attended by Sun Yat-sen. Just before the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, the Chinese Premier invited Kano to visit China at the bequest of the Empress in order to lay the basis for educating young Chinese in Japan and thus strengthen China. Kano made a thorough study of the situation, communicating with Chinese officials by the written language of kanji which is used by both nations (although the oral language is completely different).

School for Chinese in Japan

Kano recommended Kobun Gakuen be set up in Japan, but suggested Prince Saionji be consulted first since he was the Japanese Minister of Education. This was done, and in 1902 Saionji asked Kano to organize the school using professors from Gakushuin and Tokyo Educational College. The Japanese government helped support the new Kobun Gakuen which educated several hundred Chinese during the seven years of its existence. Needless to say, judo was an integral part of the school’s athletic activities.

Kano recommended Kobun Gakuen be set up in Japan, but suggested Prince Saionji be consulted first since he was the Japanese Minister of Education. This was done, and in 1902 Saionji asked Kano to organize the school using professors from Gakushuin and Tokyo Educational College. The Japanese government helped support the new Kobun Gakuen which educated several hundred Chinese during the seven years of its existence. Needless to say, judo was an integral part of the school’s athletic activities.

Although Kano was devoted to judo, he was interested in all of sports. Just as he laid the basis of modern education in Japan, he also became the father of modern sports in the country. In 1911 he founded the Japan Athletic Ass’n and became its first president. About the same time, he was named Japan’s first member of the International Olympic Committee and attended the Fifth Olympiad in Stockholm in 1912-the first Olympics in which Japan took part.

In promoting sports and physical education in Japan, Kano got a wealthy lawyer by the name of Kishi interested in sports, resulting in Kishi donating a great deal of money to the JAA. Today, the Kishi Kaikan is the headquarters for the JAA. Kano continued as JAA president until 1922, when he resigned and became honorary president of that organization.

Kudo entered the Kodokan in 1917 and started training under Kano the following year, continuing until the Shihan’s death two decades later. He learned kata personally from Kano and sometimes joined with him in demonstrating kata. The stocky little kyudan, now 71, is one of the few judoka left who has received instruction directly from Jigoro Kano.

Takasaki, who was captain of the Waseda University judo team, graduated in 1925 and immediately joined the Army’s Imperial Guard unit. A short time later he received a telegram from Kano: “Your father has been looking for a good wife for you. What sort of woman do you have in mind for a wife?” “Less than three years later,” Takasaki said, “I married his youngest daughter Atsuko.” When the first All-Japan Judo Championships were held in 1930, 71-year-old Jigoro Kano’s son-in-law, Takasaki, emerged the winner.

Reminiscence of Nango

Nango, 91-year-old nephew of the Shihan (Nango’s mother was Kano’s elder sister), also learned judo under Jigoro Kano. He studied judo for eight years and went as high as nidan. He still remembers doing randori with the judo master at the “Kano Juku” (dojo). In later years he lent financial support to the Kodokan and continued his close association with Kano right up to the time of his uncle’s death.

Nango’s impressions of the Shihan were of a sincere, well-mannered man who didn’t drink too much and was not especially humorous during the times they were together. He was strict and serious when dealing with children, Nango remembers, and attempted to be completely fair-minded. “Keichu Tokugawa, son of a former shogun, was treated no differently in judo training than any of Kano’s other students.”

Kudo saw him as responding easily to others, not quickly angered-an apparent contradiction to the way Takasaki recalled him. He listened patiently to others, never interrupting them, and then won them over to his way of thinking by logical argumentation.

Kano always fearlessly carried out what he thought was right, according to Kudo. He was extremely generous, Kudo recalls, and opposed to killing anything-even insects. Dr. Morohashi viewed Kano as a person with a many-sided personality. “He was a man of few words; once visited a hospitalized friend and spent the entire day with him without speaking a word.”

Other things Dr. Morohashi remembers: “He used to take an umbrella with him every day because he didn’t like to worry about whether or not it would rain.”

“He also had the same lunch-soba (noodles)-every day simply because he hated to bother his head about such trifling matters as what he could eat.”

“And there were times when he was so poor that when he had to entertain important guests at his home he first had to go to the pawnshop and get his formal kimono out of hock.”

Although Kano was a confirmed patriot he was never a nationalist of the same ilk as Mitsuru Toyama or Morihei Uchida. In contrast, he took the internatioanI view and was a liberal, cut from the same cloth as Prince Saionji.

In the last few years of his life Jigoro Kano concentrated on the educational and spiritual aspects of judo until the systems reached a level of intellectual and moral education as well as an athletic activity and method of combat. Actually, he referred to judo as a sport with the three aims of physical education, contest proficiency and mental training. Its ultimate object was “to perfect oneself and thus be of some use to the world around oneself.”

at the Kodokan.

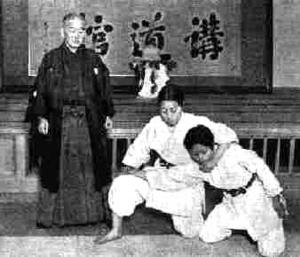

Kano taught kata until a very old age, sometimes demonstrating its techniques with his assistants. His method of teaching judo varied according to the age and experience of the student. Although he stopped doing randori at a much earlier age, he continued to stress it over kata. His idea was to have the students engage in free practice and assimilate kata naturally.

Kudo once asked Kano his reaction to proposals for dividing judoka by weight classifications for tournament competition. Kano replied, “now a small man can easily throw a big man, but if small men want to be classed by weight, I’m willing to give the proposition favorable consideration.”

Opposed Subsidies

Kano was opposed to the idea of government subsidies, but felt if the Kodokan rejected it, other foundations would not be in a position to receive grants. To keep from hurting the chances of other groups, he agreed to receive a subsidy although it was quite small. The Shihan was actually short of money and sought financial aid from the Kano clan in Naha.

The Kodokan, then located at Suidobashi, celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1934 at an impressive ceremony held in the presence of an imperial prince and with high-ranking members attending from all over Japan. It was at this time Jigoro Kano presented cash gifts to the memorial plaques of each of his departed teachers and voiced gratitude for all they had done for him. The money eventually went to the families of those instructors.

As a member of the International Olympic Committee, Kan attended every Olympic Games from the Fifth Olympiad in 1912 in Stockholm to the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, including the 10th Olympiad in Los Angeles in 1932. Kudo asked Kano if judo should be included in the Olympics and the Shihan replied: “If the IOC asks Japan to include it, then Japan will consider it.” In 1913 Jigoro Kano, accompanied by Takasaki and S. Kotani, now international secretary of the Kodokan, went to Geneva to offer Tokyo as the site for the 12th Olympiad in 1940.

In 1935 Kano received the Asahi Prize for outstanding contributions in the fields of art, science and sports. Three years later he went to an IOC meeting in Cairo and succeeded in getting Tokyo nominated for the site of the 1940 Olympics at which judo was to be included as one of the events for the first time.

It turned out to be the Shihan’s crowning achievement although a cataclysmic world war was to force its postponement for another quarter of a century. On his way home from that momentous conference on board the SS Hikawa Maru on May 4, 1938, Jigoro Kano died from pneumonia. He was 78 years old.

Another dream-an International Judo Federation, plans for which Kano revealed in 1933-came true in 1952. Today, more than six million persons practice judo in over 30 countries around the world. In October of 1969 thousands of judo fans watched the sixth World Judo Championships in Mexico City-vivid proof of Jigoro Kano’s prophetic statement, “When I die, Kodokan judo will not die with me because all things can be studied if these principles (best use of energy and mutual prosperity) are studied.”

By Andy Adams, 1970